- By Sandro Mancuso

- ·

- Posted 23 Oct 2017

What should my first test be? What should I test next? These are common questions that I'm asked over and over again. I quite often ask these questions myself. Deciding on what to test is hard. Deciding on the order that things should be tested is even harder.1 But writing tests first is not the only problem. How often did we get frustrated while dealing with existing tests which we had no idea what they are testing?

Over the years I met and paired with a lot of experienced TDD practicioners and each one of them have a slightly different way to decide which tests to write and in which order. They also have different approaches to actually write their tests. Some write the name of the test method first. Others don't bother with the name of the test method; they only appropriately name it after they write the test code. Some prefer a more exploratory approach, making a mess at the beginning, and only refactor when they have a better understanding of the problem and enough code in front of them. Others prefer a more structured approach, doing a little bit more thinking and "just-in-time design" before they write their tests. Some start typing straight away and wait to see what the code will look like before making any naming and design assumptions. Some use a more classicist approach by default. Others prefer a more mockist outside-in approach. And to make things more confusing, experienced TDD practicioners mix-and-match styles and approaches according to what they are trying to test.

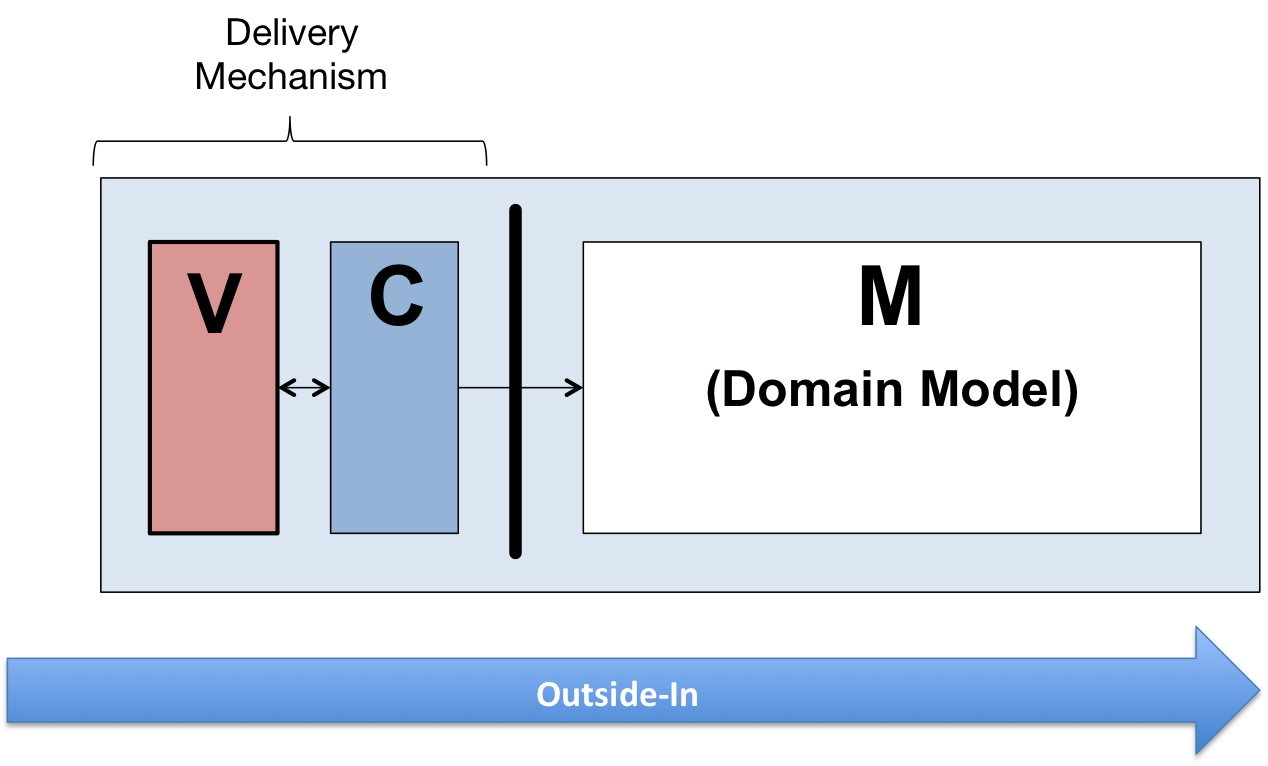

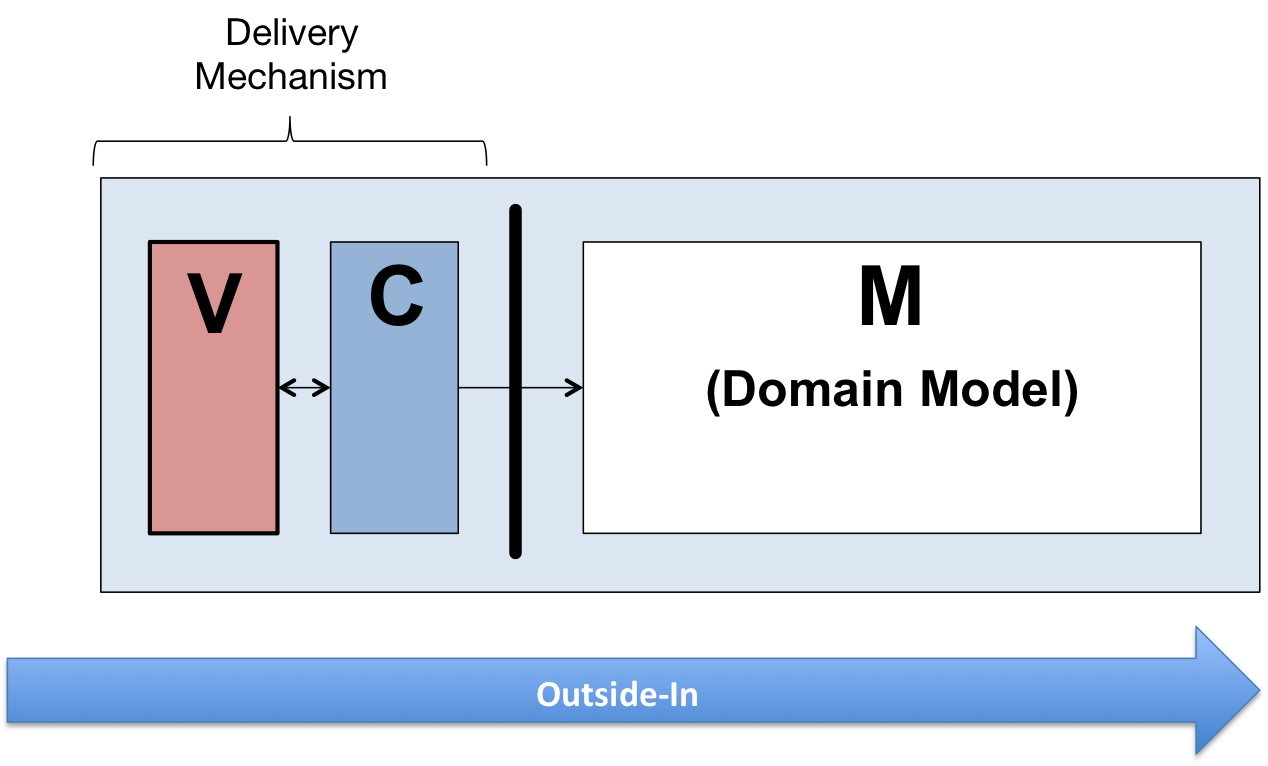

In this post I'll try to describe how I generally think about my tests. Due to the nature of the projects I'm noramlly involved with2 I tend to think and design (in my head) a little bit more before I start typing. Outside-In TDD is normally my default mode when writing tests. My main focus when writing tests is to clearly express the behaviour I want the application (or class) to have.

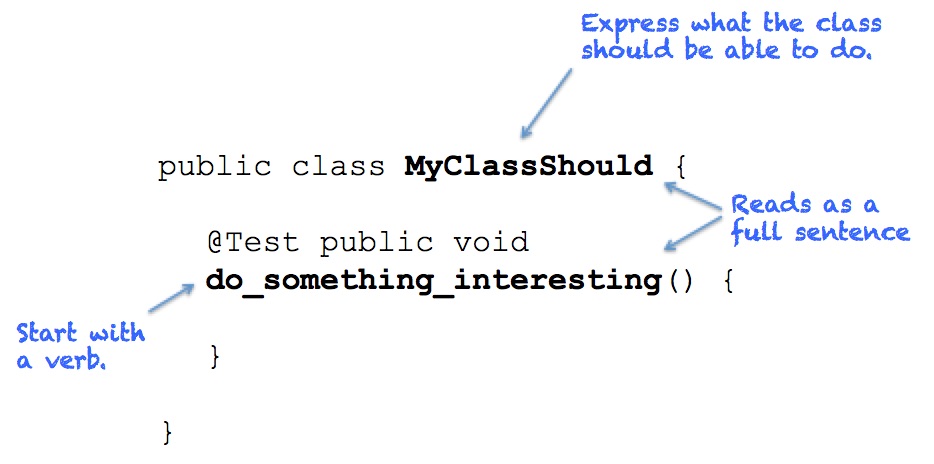

This is the template I normally use to help me decide what to test and how to name my test methods according to the expected behaviour:

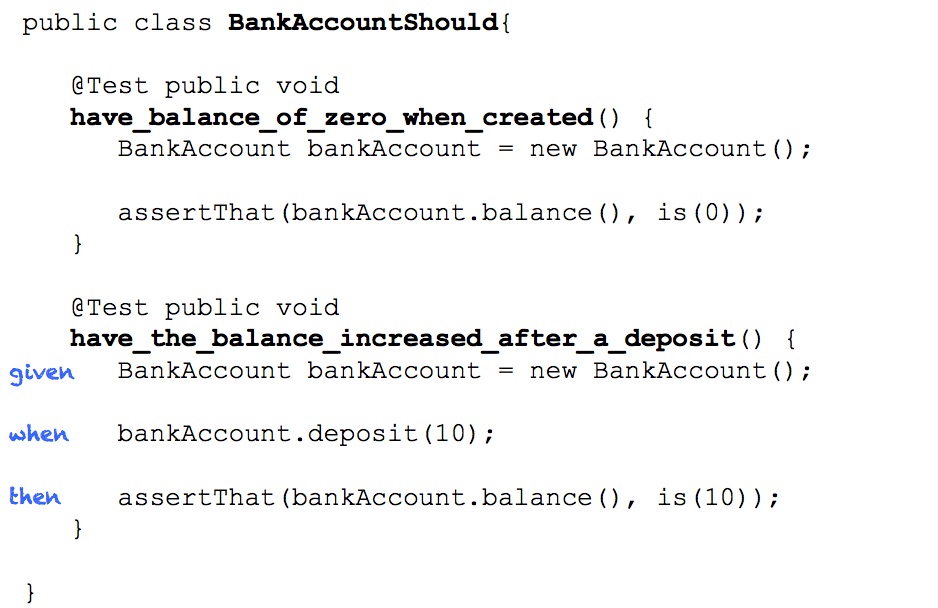

This approach forces me to think about the behaviour I want my class to have, making it easier to write my first and subsequent tests. Even at a unit test level, I try my best to name my test methods in a way that a business person could understand, rarely using any technical language. Here are a few examples:

Trying to form a sentence combining the name of the test class and the name of the test method forces me to really focus on the behaviour I want to test. Once I figure that out, it becomes quite easy to write my assertion since I just need to translate English to the programming language I'm using.

One thing to notice is that I normally split the body of my tests into 3 blocks (given, when, then). However, in some tests I call the method under test from the assertion and some tests don't need any setup. Many tests are quite simple and have only one line.

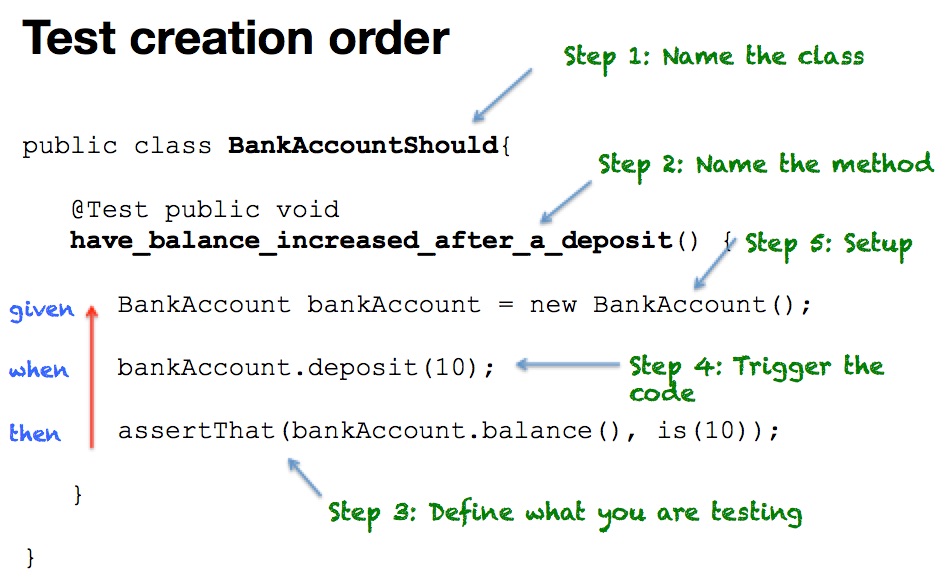

And here are the 5 steps I normally follow when creating a new test class:

For subsequent test methods I iterate through steps 2 to 5. The skeleton of the production code is generated from the test class.

Many developers don't like the use of the word "should". Some say that it is redundant and should not be used. Others say that it is not strong enough. "Must" is too strong. What about "have to"? I'm still not sure about it. For now, I'll stick with "should" but I may give "have to" a try. Since I only use it on the class name, I don't really think it is a big deal and it helps me to construct a phrase when combining with the name of the test methods.

Here are some common names I've seen given to the variable that points to the class under test:

BankAccount testee = new BankAccount();

BankAccount sut = new BankAccount();

BankAccount ba = new BankAccount();

If it is a bank account, name the variable bankAccount.

And for methods, here are some

test_deposit_works() {…} // what does 'works' mean?

test_deposit_works_correctly() {…} // should it ever work incorrectly?

test_deposit() {…} // what exactly is it testing?

check_balance_after_deposit() {…} // what is it checking?

A test name should clearly indicate why a test should pass or fail, that means, I should not need to look at the assertion(s) to figure out what the test is actually testing.

[BankAccountShould] have_balance_increased_after_a_deposit()

If the test above fails I'll have a fairly good idea why it failed.

I don't really follow rules and quite often I do things in a different way. It all depends on what I'm doing and the context I'm in. Some projects already have a standard way of writing unit tests and if I'm a new joiner, I'll comply to it. Having a standard is a good thing. It avoids confusion and (bad) surprises, regardless if the "standard" is good or not. What I described above is how I normally name and think about my tests, and it is the standard I often put in place when I start a new project. This is also how I'm teaching our apprentices at Codurance.

Ideally we would choose a sequence of small steps (tests) that could help us to gradually add functionality to our system and evolve our design.↩

Most of my work is done on bespoke business applications with a complex domain. I also normally work in projects where we constantly interact with product owners and business experts. All projects that I get involved are run using Agile methodologies. The approach I described works well for me because I normally write code according to well-defined user stories and acceptance criteria, which gives me a fairly good idea of what needs to be done before I start coding. It may not work so well if you do more exploratory work. I normally flip to a more classicist approach when I’m exploring.↩

Software is our passion.

We are software craftspeople. We build well-crafted software for our clients, we help developers to get better at their craft through training, coaching and mentoring, and we help companies get better at delivering software.