Samir Talwar

See other author's postsHere's a thing you might not see a lot.

@Test public void hungryHungryPatrons() {

KitchenStaff alice = new PieChef();

KitchenStaff bob = new DollopDistributor();

KitchenStaff carol = new CutleryAdder();

KitchenStaff dan = new Server();

alice.setNext(bob);

bob.setNext(carol);

carol.setNext(dan);

Patron patron = new Patron();

alice.prepare(new Pie()).forPatron(patron);

assertThat(patron, hasPie());

}

It might look odd, but the idea is fairly common. For example, the Java Servlets framework uses the concept of a FilterChain to model a sequence of filters upon a request.

You can use Filter objects to do pretty much anything with a request. Here's one that tracks how many hits there have been to a site. Notice that it passes the request and response objects onto the next filter in the chain when it's done.

public final class HitCounterFilter implements Filter {

// initialization and destruction methods go here

public void doFilter(

ServletRequest request,

ServletResponse response,

FilterChain chain)

{

int hits = getCounter().incCounter();

log(“The number of hits is ” + hits);

chain.doFilter(request, response);

}

}

We might use an object in the chain to modify the input or output (in this case, the request or response):

public final class SwitchEncodingFilter implements Filter {

// initialization and destruction methods go here

public void doFilter(

ServletRequest request,

ServletResponse response,

FilterChain chain)

{

request.setEncoding(“UTF-8”);

chain.doFilter(request, response);

}

}

We might even bail out of the chain early if things are going pear-shaped.

public final class AuthorizationFilter implements Filter {

// initialization and destruction methods go here

public void doFilter(

ServletRequest request,

ServletResponse response,

FilterChain chain)

{

if (!user().canAccess(request)) {

throw new AuthException(user);

}

chain.doFilter(request, response);

}

}

Basically, once you hit an element in the chain, it has full control.

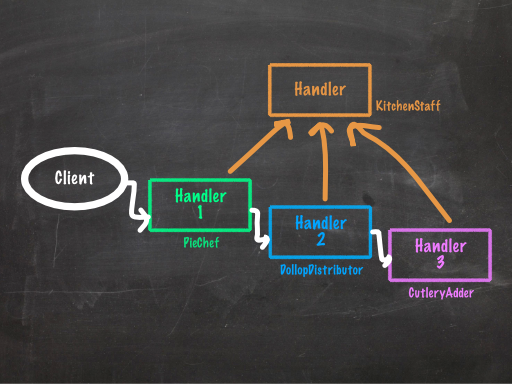

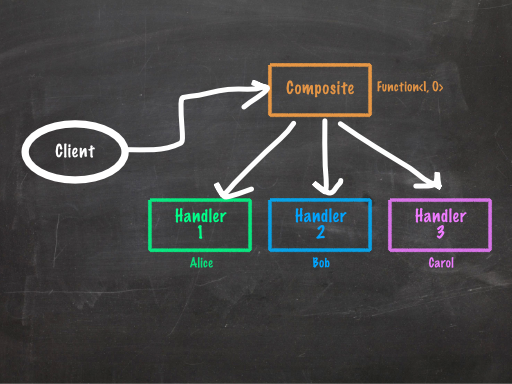

In UML, it looks a little like this:

This is probably bad practice.

This may be a little contentious, but I'd say that most implementations of the Chain of Responsibility pattern are pretty confusing. Because the chain relies on each and every member playing its part correctly, it's very easy to simply lose things (in the case above, HTTP requests) by missing a line or two, reordering the chain without thinking through the ramifications, or mutating the ServletRequest in a fashion that makes later elements in the chain misbehave.

Let's dive a little further into how we can salvage something from all of this.

Remember our hungry patron?

@Test public void

hungryHungryPatrons() {

KitchenStaff alice = new PieChef();

KitchenStaff bob = new DollopDistributor();

KitchenStaff carol = new CutleryAdder();

KitchenStaff dan = new Server();

alice.setNext(bob);

bob.setNext(carol);

carol.setNext(dan);

Patron patron = new Patron();

alice.prepare(new Pie()).forPatron(patron);

assertThat(patron, hasPie());

}

That assertion is using Hamcrest matchers, by the way. Check them out if you're not too familiar with them. They're amazing.

Step 1: Stop mutating.

Not all Chain of Responsibility implementations involve mutation, but for those that do, it's best to get rid of it as soon as possible. Making your code immutable makes it much easier to refactor further without making mistakes.

There are three cases of mutation here.

- Each member of staff has the "next" member set later, and the patrons themselves are mutated. Instead of setting the next member of staff later, we'll construct each one with the next.

- Though you can't see it, Alice, the

PieChef, sets a flag on thePieto mark it ascookedfor Bob, theDollopDistributor. Instead of changing the object, we'll have her accept anUncookedPieand pass aCookedPieto Bob. We then adapt Bob to accept aCookedPie. This ensures we can't get the order wrong, asBobwill never receive an uncooked pie. And as for the patron, we'll start off with a

HungryPatronand have them return a new instance of themselves upon feeding.@Test public void hungryHungryPatrons() { KitchenStaff dan = new Server(); KitchenStaff carol = new CutleryAdder(dan); KitchenStaff bob = new DollopDistributor(carol); KitchenStaff alice = new PieChef(bob);

Patron hungryPatron = new HungryPatron(); Patron happyPatron = alice.prepare(new UncookedPie()).forPatron(hungryPatron); assertThat(happyPatron, hasPie());}

This hasn't changed much, unfortunately. It's still very confusing why we giving the pie to Alice results in the patron receiving it, and we could still get things in the wrong order or ask the wrong person to do something.

Step 2: Make it type-safe.

Part of the problem with the ordering is that even though Alice gives the next person a CookedPie, we could tell her to give it to anyone, resulting in a ClassCastException or something equally fun. By parameterising the types, we can avoid this, ensuring that both the input and output types are correct.

@Test public void

hungryHungryPatrons() {

KitchenStaff<WithCutlery<Meal>> dan = new Server();

KitchenStaff<Meal> carol = new CutleryAdder(dan);

KitchenStaff<CookedPie> bob = new DollopDistributor(carol);

KitchenStaff<UncookedPie> alice = new PieChef(bob);

Patron hungryPatron = new HungryPatron();

Patron happyPatron = alice.prepare(new UncookedPie()).forPatron(hungryPatron);

assertThat(happyPatron, hasPie());

}

Each of our constructors will change too. For example, PieChef's constructor used to look like this:

public PieChef(KitchenStaff next) {

this.next = next;

}

And now its parameter specifies the type it accepts:

public PieChef(KitchenStaff<CookedPie> next) {

this.next = next;

}

Step 3: Separate behaviours.

KitchenStaff does two things: prepare food, but also hand over the food to the next person. Let's split that up into two different concepts. We'll construct an instance of KitchenStaff, then tell them who to delegate to next.

@Test public void

hungryHungryPatrons() {

KitchenStaff<WithCutlery<Meal>, Serving> dan = new Server();

KitchenStaff<Meal, Serving> carol = new CutleryAdder().then(dan);

KitchenStaff<CookedPie, Serving> bob = new DollopDistributor().then(carol);

KitchenStaff<UncookedPie, Serving> alice = new PieChef().then(bob);

Patron hungryPatron = new HungryPatron();

Patron happyPatron = alice.prepare(new UncookedPie()).forPatron(hungryPatron);

assertThat(happyPatron, hasPie());

}

In this situation, then doesn't modify the object directly, but instead returns a new instance of KitchenStaff who knows to pass it on. It looks something like this:

private static interface KitchenStaff<I, O> {

O prepare(I input);

default <Next> KitchenStaff<I, Next> then(KitchenStaff<O, Next> next) {

return input -> {

O output = prepare(input);

return next.prepare(output);

};

}

}

To do this, we also have to return a value rather than operating purely on side effects, ensuring that we always pass on the value. In situations where we may not want to continue, we can return an Optional<T> value, which can contain either something (Optional.of(value)) or nothing (Optional.empty()).

Step 4: Split the domain from the infrastructure.

Now that we have separated the chaining from the construction of the KitchenStaff, we can separate the two. alice, bob and friends are useful objects to know about in their own right, and it's pretty confusing to see them only as part of the chain. Let's leave the chaining until later.

@Test public void

hungryHungryPatrons() {

KitchenStaff<UncookedPie, CookedPie> alice = new PieChef();

KitchenStaff<CookedPie, Meal> bob = new DollopDistributor();

KitchenStaff<Meal, WithCutlery<Meal>> carol = new CutleryAdder();

KitchenStaff<WithCutlery<Meal>, Serving> dan = new Server();

KitchenStaff<UncookedPie, Serving> staff = alice.then(bob).then(carol).then(dan);

Patron hungryPatron = new HungryPatron();

Patron happyPatron = staff.prepare(new UncookedPie()).forPatron(hungryPatron);

assertThat(happyPatron, hasPie());

}

So now we have a composite object, staff, which embodies the chain of operations. This allows us to see the individuals as part of it as separate entities.

Step 5: Identify redundant infrastructure.

That KitchenStaff type looks awfully familiar at this point.

Perhaps it looks something like this:

@FunctionalInterface

public interface Function<T, R> {

R apply(T t);

...

default <V> Function<T, V> andThen(Function<? super R, ? extends V> after) {

Objects.requireNonNull(after);

return (T t) -> after.apply(apply(t));

}

...

}

Oh, look, it's a function! And then is simply function composition. Our KitchenStaff type appears to be pretty much a subset of the Function type, so why not just use that instead?

@Test public void

hungryHungryPatrons() {

Function<UncookedPie, CookedPie> alice = new PieChef();

Function<CookedPie, Meal> bob = new DollopDistributor();

Function<Meal, WithCutlery<Meal>> carol = new CutleryAdder();

Function<WithCutlery<Meal>, Serving> dan = new Server();

Function<UncookedPie, Serving> staff = alice.andThen(bob).andThen(carol).andThen(dan);

Patron hungryPatron = new HungryPatron();

Patron happyPatron = staff.apply(new UncookedPie()).forPatron(hungryPatron);

assertThat(happyPatron, hasPie());

}

Step 6: Optionally replace classes with lambdas and method references.

Sometimes you really don't need a full class. In this case, the implementation is simple enough that we can just use method references instead.

@Test public void

hungryHungryPatrons() {

Function<UncookedPie, CookedPie> alice = UncookedPie::cook;

Function<CookedPie, Meal> bob = CookedPie::addCream;

Function<Meal, WithCutlery<Meal>> carol = WithCutlery::new;

Function<WithCutlery<Meal>, Serving> dan = Serving::new;

Function<UncookedPie, Serving> staff = alice.andThen(bob).andThen(carol).andThen(dan);

Patron hungryPatron = new HungryPatron();

Patron happyPatron = staff.apply(new UncookedPie()).forPatron(hungryPatron);

assertThat(happyPatron, hasPie());

}

This drastically cuts down on boilerplate and lets us see what's actually going on.

Our new structure is quite different—far more so than the earlier examples.

By decoupling the business domain (in this case, pie preparation) from the infrastructure (composed functions), we're able to come up with much cleaner, terser code. Our behavioural classes (focusing around preparation) disappeared, leaving only the domain objects themselves (UncookedPie, for example) and the methods on them (e.g. cook), which is where the behaviour should probably live anyway.

Related Blogs

Get content like this straight to your inbox!

Software is our passion.

We are software craftspeople. We build well-crafted software for our clients, we help developers to get better at their craft through training, coaching and mentoring, and we help companies get better at delivering software.

Latest Blogs

Software Modernisation and Employee Retention...

Becoming PCI Compliant

Codurance signs the Microsoft Partner...

Useful Links

Contact Us

London, EC1M 5PU

Phone: +44 207 4902967

2 Mount Street

Manchester, M2 5WQ

Phone: +44 161 302 6795

Carrer de Pallars 99, 4th floor, room 41

Barcelona, 08018

Phone: +34 937 82 28 82

Email: hello@codurance.com