- By Sandro Mancuso

- ·

- Posted 23 Oct 2017

We all say that software design is all about trade-offs but how do we actually reason about it? How do we decide how much code we are going to write for a given task? Is the easiest thing that could possibly work the right approach? The simplest? How do we know the difference between simple and easy? Is this even the right question?

One way or another, subconsciously or not, we always make a decision to start implementing a new behaviour from somewhere. Some of us write just enough code to satisfy the new behaviour. Others write way more code, trying to avoid future rework in case things change or evolve. Many others are somewhere in between.

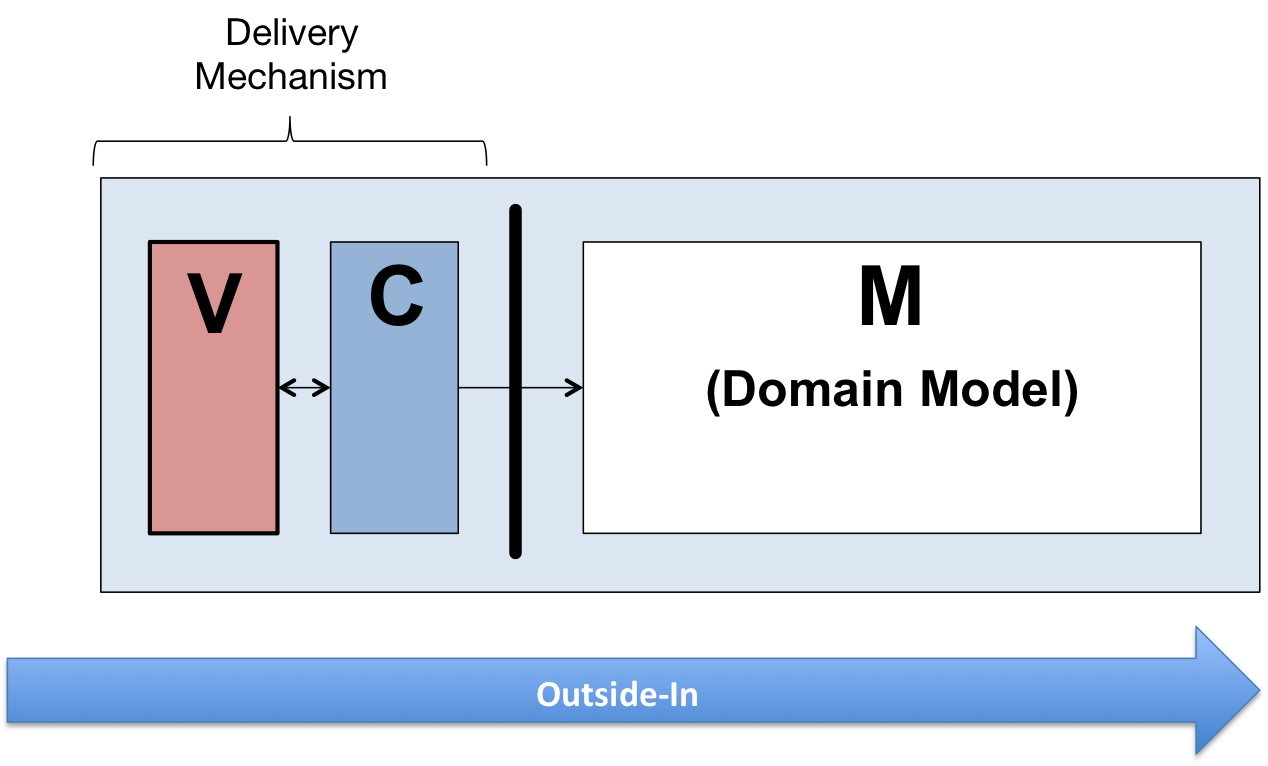

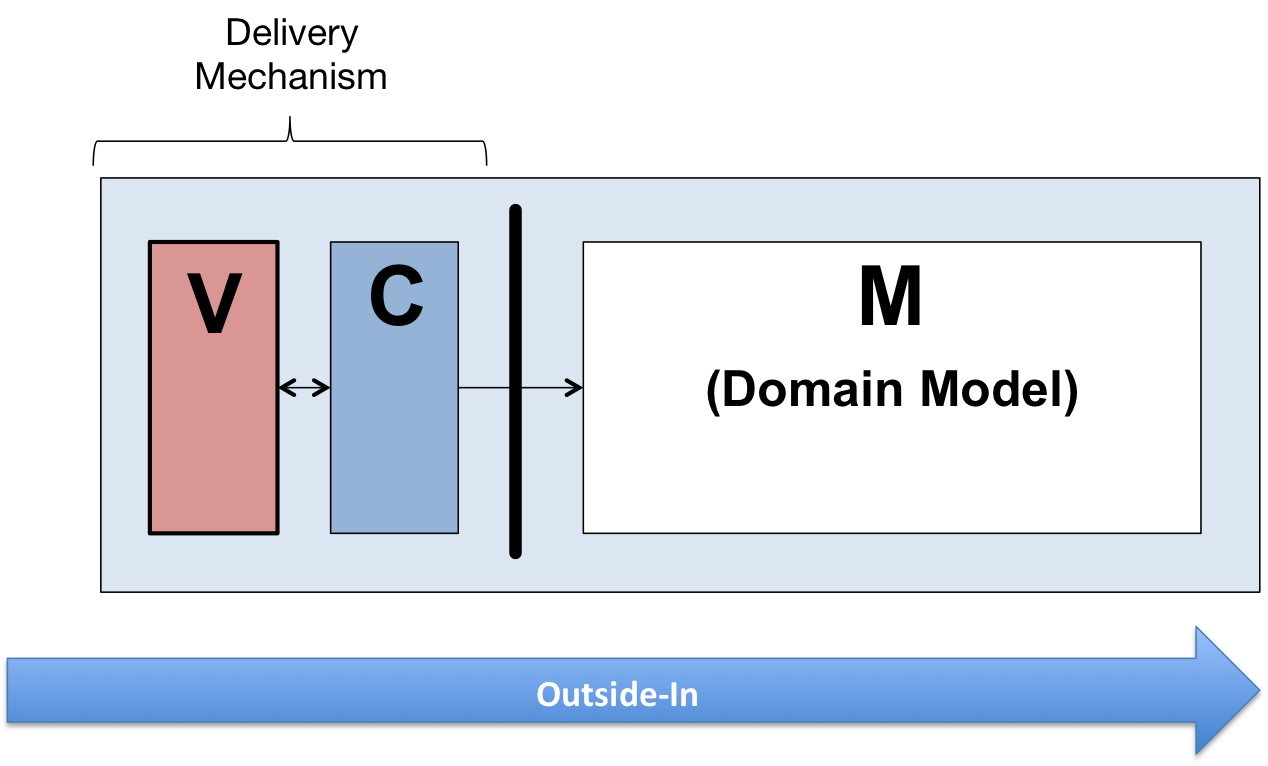

Let’s assume the following:

On the left hand side, we have the most straightforward solution for a given desired behaviour. On the right hand side, we have infinite possibilities for writing future proof code. The problem with the right side is that we could never write future proof code according to infinite future possibilities. But we can, however, pick a software capability and try to write some future proof code for that. E.g:

Although we could try, writing code that can remain flexible for the entire lifespan of a project is practically impossible. You will get it wrong, no matter what you do. Besides that, you will be adding complexity all over the place since there is no way we can know for sure which areas of our code base will evolve.

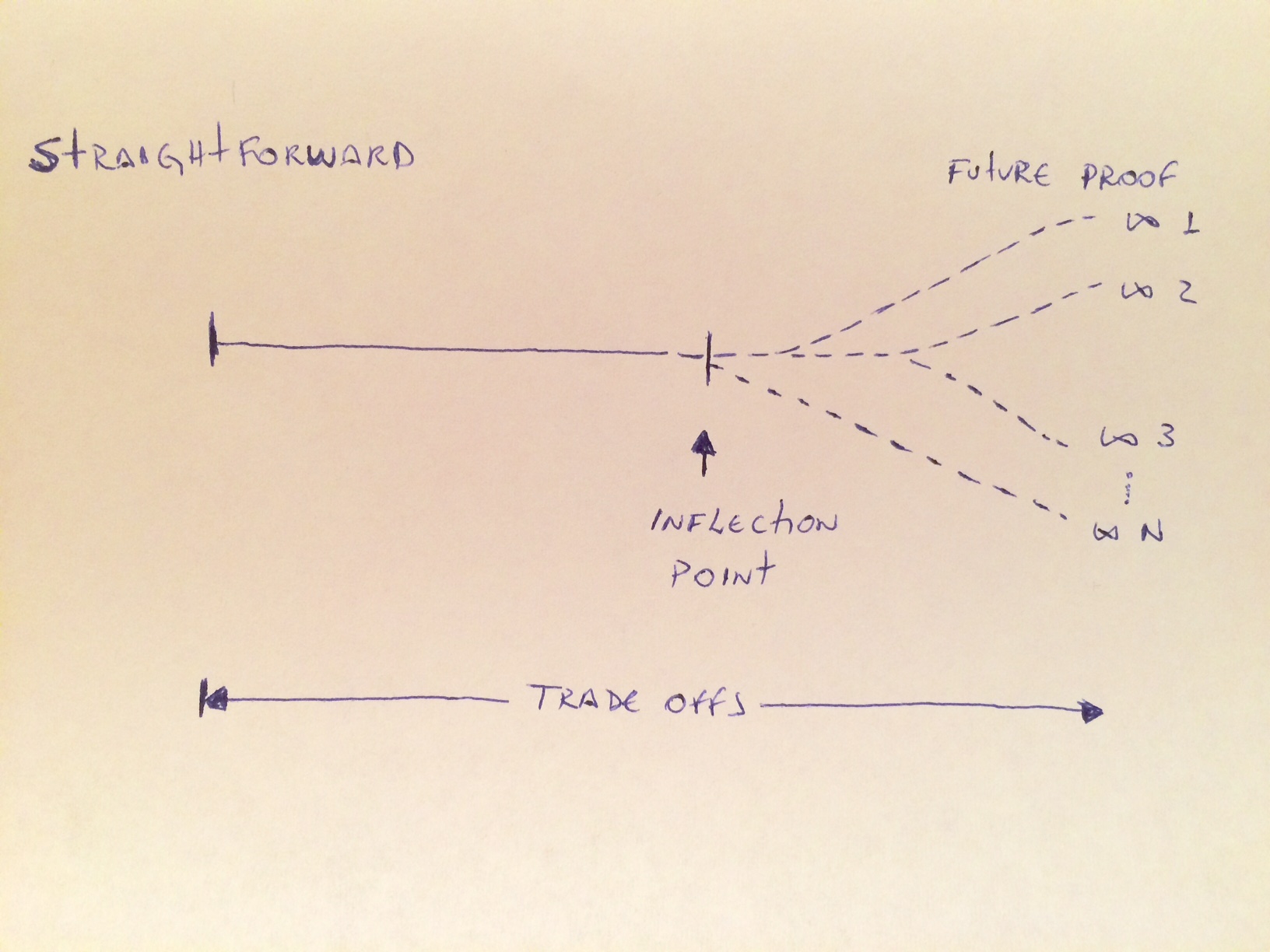

I don’t think there is a clear solution or guideline for this problem but at least there is a better way to reason about that. I call it inflection point.

Inflection point defines the maximum amount of investment we are comfortable to make in a desired type of flexibility at a given moment in time. Beyond this point, the investment is not worth anymore.

There are two ways to reason about the inflection point:

Right-to-left: We pick a software capability that we judge to be very important in the near future. We then think about what would be our ideal solution for that software capability. From that point, which may be quite far on the right hand side, we start thinking how we could make our solution more straightforward (probably also cheaper and faster to implement) right now without loosing site of the flexibility we would like to have in the future. We keep discussing how we can simplify the solution until we find a point where making it simpler will mean loose so much flexibility that it will be too expensive to move towards our ideal solution in the future. That is the inflection point, coming from right to left.

Left-to-right: We start from the most straightforward solution for a given problem. We then think about what we currently know about the project, features that are definitely going to be implemented next, and the important software capabilities that will need to be provided in the near future. With that knowledge, we can decide how flexible we could make our code right now, moving from a straightforward solution towards a more engineered solution up to a point that the cost of the flexibility we are providing right now is just not worth the effort or it is just to speculative and risky. That’s the inflection point coming from left to right.

Let’s look at some common scenarios. Take them with a pinch of salt since there are many other factors that could make them invalid or sway the inflection point to a different side. Also, the team’s experience in certain technologies and approaches will also impact on what is considered straightforward and the cost of added flexibility.

Should we split a web page structure (HTML) from its data or should we have our backend generate the whole page via a template engine and return the whole page in one go?

What are we pre-optimising for? What type of flexibility do we want to provide now and what impact would it have in our code?

Splitting the page structure from data can bring future benefits like a stable RESTful API for other clients (mobile, other systems). It could also make it easier to write automated tests for our application when it comes to the data it returns. Besides that, we can provide a better user experience since the page will load faster or not even reload at all, depending on the implementation (single/multi page). In order to achieve that, we need to use JavaScript in the front end and provide multiple controller methods in the back end. We may need to convert objects to JSON and comply to the REST guidelines. There will be more code in the front and back end, and a few data translation layers. We will probably need to use different programming languages in the front and back end.

A different approach would be to use a template engine and render the whole pages on the server. That could be “easier” since template engine libraries are quite mature in most major languages and we keep the whole application writing in a single programming language. For back end developers, that can be more straightforward. But what do we loose? Do we have a worse user experience? Well, maybe. Internet connection today is much faster than it was 10-15 years ago, when using AJAX was a must (and also pretty hard—browser wars anyone?). What about the flexibility to add new clients (mobile / other systems)? Can we really foresee what type of API they will need? What about the API granularity? Would it be the same one used for the web?

Then we have things like team skills set. How familiar are we with all the technologies involved? How concrete are the plans to have a mobile presence? Would it be a native app or a responsive web page would do just fine?

Do we have a separate web design / UX team? Which approach would be easier to make them part of the team and work on the same code base?

Where is the inflection point? How much complexity should we add right now? Is some extra code really a big deal for the amount of flexibly we get, even if a bit speculative? Are there any other alternatives to provide a similar flexibility without so much extra code? How much would we pay if we delay the decision to provide the flexibility right now?

When our work is most exploratory, I would strongly recommend looking for the most straightforward solution. However, when working in an environment where we have a Product Owner with a clear vision, a product backlog that is carefully maintained, and with big enough budget to guarantee that the project will run for many months, if not years, should we always aim for the most straightforward solution?

Imagine that we are working on Feature A and that we know that Feature B and C are the next features to be implemented. Also, imagine that they are closely related, that means, Feature B and C will be built on top of the implementation of Feature A.

In this scenario, should we aim for the most straightforward solution for Feature A and then refactor everything in order to add Feature B and C? How far do we go with the implementation of Feature A when we are 99% sure that Feature B and C are going to implemented immediately after we finish Feature A? But what if we were only 50% sure? Or 20%? Where would the inflection point be?

Many developers use some sort of layered architecture. A common layer would be the data layer that is normally defined by repository classes.

In almost 20 years of career, I had only one application that we actually changed our persistency mechanism and the repository layer was extremely useful. Moving from one database to another had almost zero impact in the rest of the code.

I recently had a few discussions about the data (repository) layer. Some of my colleagues said that this added complexity not always pays off since we are probably not going to change the persistency mechanism. That is a fair comment and normally the repository layer can be seen as future proof code and not the most straightforward solution.

But what is the alternative? Active Record? Have persistency logic mixed with application logic? Violation of SRP? No separation of concerns? A different type of separation that will be very similar to the repositories but less explicit? Use of a framework? How does it affect transactional boundaries? Should they be in the repository layer or should they be at the entry points of your domain model?

This is an example where discussing what would be the straightforward solution versus what type of future proof code we want to have may differ a lot from team to team. Some would find a layer of repositories a very cheap price to pay while others would find it too expensive.

So, instead of discussing the repository layer, we should discuss what type of flexibility we would like to have when it comes to persistency and how much are we wiling to pay for that right now. What would the inflection point be?

Should we start an application with a monolith or with a bunch of micro-services? Or somewhere in between? Normal services? Application modules? Well-defined package/namespace structure? This is not a simple question and the inflection point will change significantly according to the context. Are we working for a small startup with two developers? Are we working with a large company with budget for a multi-year project, which will start with 50 developers from day one? How much do we know about the domain? Are we exploring an idea? Or is it a well-defined domain?

What are we optimising for? How much does it cost? How complex is the solution? What are the trade offs? Should we pre-optimise for scalability or should we focus on the most straightforward? What do we loose or gain with a given solution? Can we defer this decision to a later stage? Would it be too chaotic to have all the developers working on the same code base? Which software capabilities do we want to have in the first release? What would be the cost to make some architectural decisions in the future?

I worked in projects where it made sense to start small and grow the application bit-by-bit, focusing on the most straightforward solutions at the beginning. But I also worked in much larger applications where it was too risky or close to impossible to defer certain architectural decisions. The inflection point was completely different in those two contexts.

Many agree that the use of primitives to represent domain concepts is bad. So, should we create types for everything? What is the cost and how much more code do we need to write? Is the amount of code the only concern? Are we trying to reduce the number of bugs in the future? What about languages without types?

What price do we pay when we create types for everything? Does it really improve readability? What gains do we have in the future? Should we limit type creation to our domain model? When is it OK to use primitives? What is the impact in maintainability and testing? Would we need to write more or less tests when choosing primitives over types? How easy is to create types in our chosen programming language?

Those are many of the considerations that may define where the inflection point will be.

Over-engineering has a big cost and may cause a lot of damage. However, a long sequence of straightforward solutions may also cause of lot of pain and re-work as the system grows. Every change becomes a huge refactoring task.

As a general guideline, I prefer to first look at what would be the most straightforward solution and then start exploring a few possibilities to provide more flexibility for future changes given an important software capability (left to right). Also, most straightforward doesn’t mean quick and dirty.

However, there are times when we know that certain things are very important and considering them in the early stages of a project, or while building a new feature, may be quite beneficial. Maybe the price we pay now for some extra code may be considered a bargain when compared to the amount of flexibility we gain in the future, which will move the inflection point more towards the right.

Whenever you have a design discussion with your pair or team, focus the discussion on finding the inflection point. This will make the discussion more objective. Instead of “my idea versus yours” or “this approach versus that approach”, we should discuss what type of flexibility we would like to have and how we can achieve that without paying premium for it. How much are we willing to pay? Should we pay for it now, or in the future? Distant or near future? Can we pay in instalments?

Trying to answer the questions above will help us to reason about our decisions and find a good starting point (inflection point) for new projects or features.

Thanks to Samir Talwar, Mashooq Badar, Tom Brand, and Johan Martinsson for the conversations during Socrates UK that led to the clarification of the terminology and ideas described in this post.

Software is our passion.

We are software craftspeople. We build well-crafted software for our clients, we help developers to get better at their craft through training, coaching and mentoring, and we help companies get better at delivering software.