Sandro Mancuso

See author's bio and postsWhile working on one of our internal tools, I decided to make a small comprise and not follow my own advice. We are building a mini CRM tool and the initial requirements were:

- Maintain information about the companies we are dealing with;

- Maintain a list of contacts per company;

- Maintain a list of engagements (projects, training, consultancy) per company.

NOTE: I’ll omit details of the code, attributes, etc in order to keep this post simple.

Starting small, while building the CRUD for Company, I ended up with a Company entity that looked like this:

class Company {

+ id: CompanyId

+ name: String

}

That was all well and good. Then I needed to write code in order to maintain a list of contacts for each company. I ended up with the following:

class Contact {

+ id: ContactId;

+ companyId: CompanyId;

+ name: String

+ email: String;

}

class Company {

+ id: CompanyId;

+ name: String;

+ contacts: List[Contact];

}

That was the beginning of the problems. For the “View Company” page, I needed to display data related to the Company and all its contacts. For the pages that were only dealing with Company data (a page that listed all companies, page for edit/delete company), I didn’t need the contacts information. Should I load the contacts every time I loaded a company? Should I not load them? The problem of not loading the contacts in certain occasions is that, as the code evolves, I would not know if the list of contacts inside Company was empty because the company doesn’t have contacts or because they were not loaded. That’s confusing. Since performance is not a concern in this application, I decided to load the list of contacts every time I needed a company. Problem solved.

In the next feature I had to maintain engagements (CRUD) for a company. Following the same approach I used for contacts, I ended up with the following entities:

class Engagement {

+ id: EngagementId;

+ companyId: CompanyId;

+ name: String

+ startDate: Date;

+ endDate: Date;

+ description: String;

}

class Company {

+ id: CompanyId;

+ name: String;

+ contacts: List[Contact];

+ engagements: List[Engagement];

}

At this point, things got very confusing. I had pages that needed Company and its contacts and engagements. Pages that only needed Company and Engagements, pages that only needed Company and Contacts. But the problems were not only related to what to load and where. I had loads of code that was relying on the Company structure.

The application is a web app using AngularJS in the front with JSON going to the browser and back into the application. For that, I had JSON converters that would convert JSON to and from objects. I also had quite a lot of tests for my API and inner layers which would use builders to assemble data. In summary, there was quite a lot of code that, in order to satisfy all the features, would rely on the structure of the Company entity. This code “had to know” when contacts and engagements were loaded or not. And of course, that was constantly changing while we were deciding how much information we needed on each page.

As features stabilised and I made a few more changes in the code, everything was working.

The ripple effect

As we thought we were ready to start building other features (dashboard, financial information, forecasts, notes, reminders, follow up actions, etc), we realised we missed something important.

Some of our projects come through partners (other companies). That means that an engagement may have more than one company involved. This could make the relationship between Company and Engagements a bit different. Maybe the relationship between Company and Engagements wouldn’t be a one to many anymore. It would probably be a many to many.

class Engagement {

+ id: EngagementId;

+ companies: List[Company];

+ name: String

+ startDate: Date;

+ endDate: Date;

+ description: String;

}

class Company {

+ id: CompanyId;

+ name: String;

+ contacts: List[Contact];

+ engagements: List[Engagement];

}

I thought that it would be an easy change but I was surprised to see the massive ripple effect that it had in my code. Loads of test data, builders, JSON parsers, and API structure would be impacted and that was not a good feeling. I was really disappointed with myself and quite pissed off to be honest.

Following my own advice

A few years ago I came across CQS and later on CQRS. At the beginning I didn’t give CQS much attention and it was only with CQRS that I actually understood a different way to design software. Since then, I’ve been a strong advocate of separating the data structures (and yes, I treat entities as data structures) I use to write from the ones I use to read. I’m not talking about independently deployable read/write models, different databases, events, messages, etc. I’m only talking about using different objects to write and read data.

Fixing the problem (1st solution)

After another discussion, we decided that an Engagement would always be for a Company but it may have come to us through a partner. That changed things again. So, I decided to do the following: remove all the dependencies (attributes containing other entities or list of entities) from all the entities. Then ended up like that:

class Company {

+ id: CompanyId

+ name: String

}

class Contact {

+ id: ContactId;

+ companyId: CompanyId;

+ name: String

+ email: String;

}

class Engagement {

+ id: EngagementId;

+ companyId: CompanyId;

+ partnerId: Optional[CompanyId];

+ name: String

+ startDate: Date;

+ endDate: Date;

+ description: String;

}

With this approach, the entities would contain just the data they needed to be persisted.

But I still had the queries to fix, where many of them would need a combination of these entities. For that, I created “read” objects that would contain exactly the data needed for each query. Some of them looked like this:

class CompanyWithContacts {

+ company: Company;

+ contacts: List[Contacts]

}

class CompanyWithContactsAndEngagements {

+ company: Company;

+ contacts: List[Contacts];

+ engagements: List[Engagements];

}

class EngagementWithCompanies {

+ engagement: Engagement;

+ client: Company;

+ partner: Optional[Company];

}

With this approach, each query would return the combination of data that was requested by the delivery mechanism (pages on the website). Changes in how my entities relate to each other didn’t cause a ripple effect of changes any more since just specific queries would break. There were no problems with lazy-load / eager fetch anymore. There were no doubts about empty attributes since there were no attributes anymore. The optional ones could easily be marked as optional (thanks Java 8).

Fixing the problem (2nd solution)

After the fix above, I was reasonably happy since I was able to localise changes when entity relationships changed. But there was a bit more to it. On the positive side, they allowed me to make a single call from a page that needed a combination of data. On the negative side, performance was not a real concern for me and I didn’t want these extra objects with weird names hanging around. I still had to write code to populate them and convert them to JSON.

I then decided to make multiple calls from my pages. If a page needed a company, a list of contacts and a list of engagements related to that company, I would make three calls from the page. This decision made all the “read” objects go away and still kept my code very simple.

Conclusion

Keep your entities detached from each other and focus on implementing simple queries from the client. Just move to a single query if performance really proves to be an issue.

Don’t use ORMs. ORMs would have made my changes even worse as I would have to keep my entities and database synchronised. It’s great to have the freedom to get a record set from the database using whatever query you want and populate your objects the way you want.

The way we query data changes far more often than the way we persist the data and these changes can slice and dice the data in many different ways. Binding your entities together will only make it harder to satisfy all the queries and will put an unnecessary strain on the code that is only supposed run business logic and store data.

Related Blogs

- By Sandro Mancuso

- ·

- Posted 23 Oct 2017

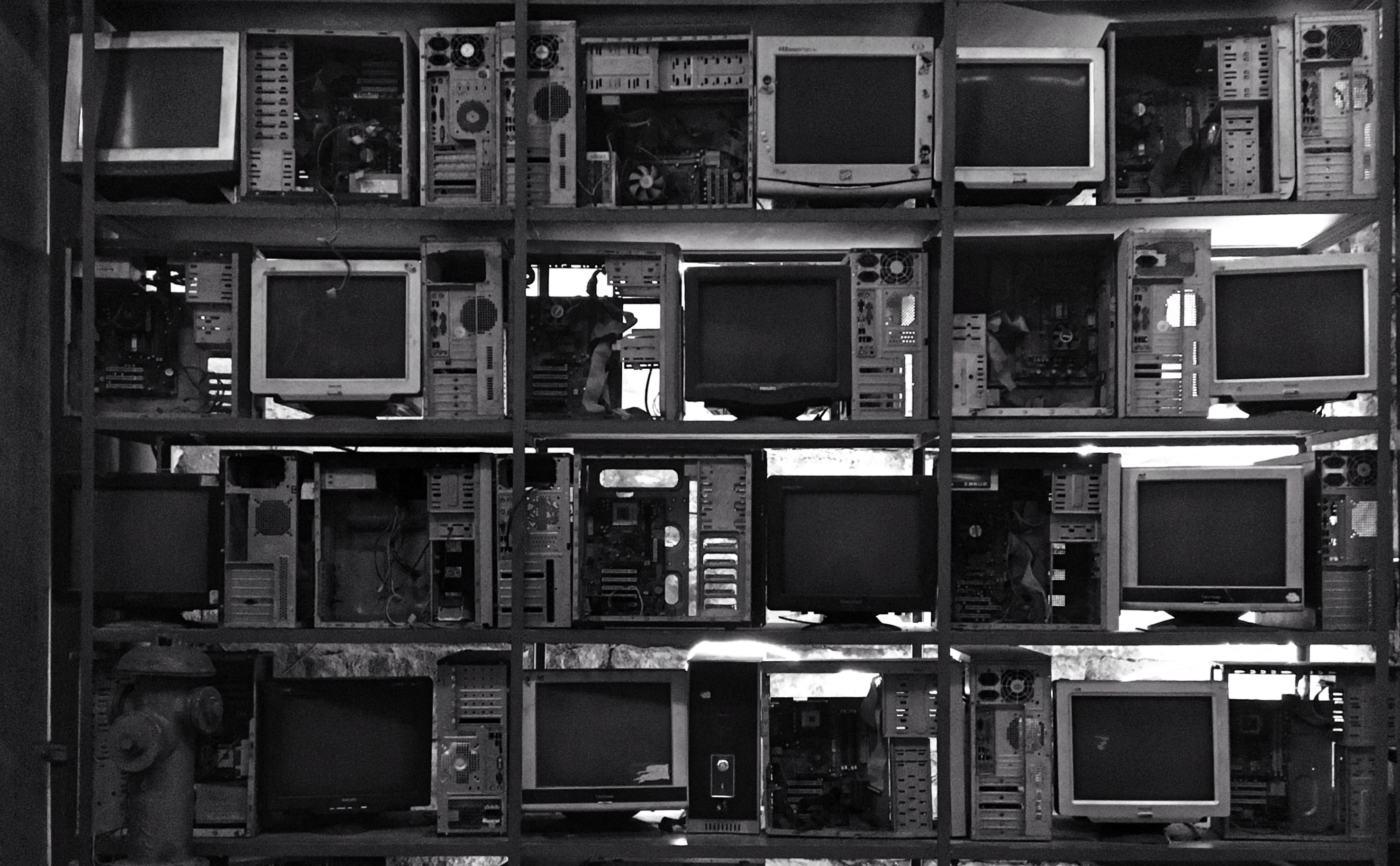

A Case for Outside-In Development

- By Sandro Mancuso

- ·

- Posted 06 May 2015

Q&A about The Software Craftsman

Get content like this straight to your inbox!

Software is our passion.

We are software craftspeople. We build well-crafted software for our clients, we help developers to get better at their craft through training, coaching and mentoring, and we help companies get better at delivering software.

Latest Blogs

Software Modernisation and Employee Retention...

Becoming PCI Compliant

Codurance signs the Microsoft Partner...

Useful Links

Contact Us

London, EC1M 5PU

Phone: +44 207 4902967

2 Mount Street

Manchester, M2 5WQ

Phone: +44 161 302 6795

Carrer de Pallars 99, 4th floor, room 41

Barcelona, 08018

Phone: +34 937 82 28 82

Email: hello@codurance.com