Felipe Fernández

See other author's postsHandling state is one of the cornerstones of software development. Most of business value derived from software relies on state. Depending on the level of abstraction, state, and the approach to handle it, looks like a completely different problem. In this post we'll see what is common to all of them and how modern scalability needs have pushed towards innovative and refreshing approaches.

Levels of abstraction

Ted Malaska's presentation about Spark serves as inspiration for this post. In this screenshot, Ted shows a list of concepts that we have to understand when learning to code:

You can stop reading here and spend some time thinking about your conceptions of state at any of those levels. When you're done, come back here and let's try to define more formally what state is.

State definition

If you went through a similar train of thoughts like myself these concepts appear for sure: mutability, concurrency, isolation and scope. Most of them have to do with the level of abstraction or the strategy to handle state, not with the definition itself. Let's try to extract the essential from Wikipedia's definition):

The state of a digital logic circuit or computer program is a technical term for all the stored information, at a given instant in time, to which the circuit or program has access.

Data at a given instant in time. Neither behaviour, nor abstractions around it, but pure data.

Out of the tar pit paper has powerful insights about state from a more radical concept than scalability: complexity.

One final point is that the type of complexity we are discussing in this paper is that which makes large systems hard to understand. It is this that causes us to expend huge resources in creating and maintaining such systems. This type of complexity has nothing to do with complexity theory — the branch of computer science which studies the resources consumed by a machine executing a program.

State at service level

Through this post we'll see how simplicity and scalability aligns blissfully when handling state. Let's start with approaches to handle state at service level. We'll then move into distributed systems integration.

Global State

This is the loosest approach, e.g. public static non final variables in Java. How can we informally reason about code that uses global variables? We need to inspect all the code that is mutating that variable, and those lines of code might live in completely unrelated parts of the system. Having to reason about plenty of pieces at the same time is inefficient and dangerous. Global state forces us to do black box testing as the pieces of our system are coupled through global state.

A priori simple lines of code get quickly 'contaminated' by the complexity deriving from state:

The key problem is that a test (of any kind) on a system or component that is in one particular state tells you nothing at all about the behaviour of that system or component when it happens to be in another state.

Object Oriented Programming State

In most forms of object-oriented programming (OOP) an object is seen as consisting of some state together with a set of procedures for accessing and manipulating that state.

As Uncle Bob said once, programming paradigms succeed, paradoxically, by removing power. Java succeeds because it removed from developers the power to manage memory. OOP strongly suggests that code that mutates state should be colocated with that state. That guarantee, along preconditions and postconditions, makes code much easier to reason about and test.

Using inheritance to share code is a bad idea based on those premises. State mutators will be located in different files, even if they finally constitute a single object at runtime, obscuring the readability of the code.

Functional Programming State

FP tries to solve this complexity avoiding mutable state completely. Thanks to that we can have functions whose outputs depend completely on their inputs. Avoiding is not as simple as closing your eyes, though. There are some scenarios where we need to handle state. Let's use an example from Functional programming in Scala book:

case class Simple(seed: Long) extends RNG {

def nextInt: (Int, RNG) = {

val newSeed = (seed * 0x5DEECE66DL + 0xBL) & 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFL

val nextRNG = Simple(newSeed)

val n = (newSeed >>> 16).toInt

(n, nextRNG)

}

}

This random numbers generator class depends on the previous seed to generate new random numbers. The OOP approach would be keeping the old seed as state of an object and mutating it every time that nextInt is called. FP approach encapsulates that seed in a tuple along the result. Everything is immutable and the result of a function is deterministic depending on the input. That property is called Referential Transparency and we can see its power if we think in terms of composability and modularity.

Actor State

Akka is a toolkit that implements the Actor Model. This model handles state with a mix of OOP and FP. This post talks about the three basic rules for Akka concurrency.

Rule 1: Each actor processes the messages from its inbox sequentially (not concurrently). So a clerk never picks two or more messages and works them side-by-side.

Rule 2: If an actor sends to another actor two messages in a particular order then the receiving actor will receive them in the same order. So clerks can outsource work to their colleagues but again, they must take one message after the other out of the inbox and transfer them one after the other to the colleague.

Rule 3: All messages sent to actors must be immutable objects.

Every actor manages its own state, but the processing happens sequentially, so no locking is required. This, plus the message delivery order guarantees and the immutability of the exchanged messages, creates a reliable, scalable and easy to understand model for handling state.

Summary of state at service level

At this point, we've already covered variables, flow control statements (not really relevant for this post), functions, objects and threads. We focused on complexity more than scalability, but my opinion is that those ideas are aligned. To reduce the complexity derived from state at service level, we learned that the following properties are convenient:

- Isolation

- Avoiding state as much as possible

- State should be managed by specialised software

- Immutability

- State and behaviour affinity

Let's see how those ideas apply to system level. That corresponds to Distribution in the Learning Code list seen before.

State at system level

State is data at a given instant in time. But what is the lifespan of that state? Request scoped? Session scoped? Could it be flushed out when a service crashes? Or should it be persisted in a durable storage?

Request scoped: let's imagine an object is holding a Finite state machine during the lifespan of an HTTP request. This scope is really short so we could keep the state in memory. Most of the times we could simply retry on failures instead of using something more complicated like Akka Persistence.

Session scoped: HTTP is a stateless protocol. Remember that time is the fundamental word in our definition of state. That means that HTTP doesn't have any built-in mechanism to keep track of state. The concept of session involves a logical group of HTTP requests with some internal state. Classic solution was keeping that state in memory on the service. This solution goes against horizontal scalability. The main point of having stateless services is being able to route requests to different services depending on health and current load of those services. That's not possible when every single service is coupled with the clients through that session state.

Stream scoped: this is the domain of near real time analytics. State is scoped for a window of time to calculate some analytics such as average, count or max.

Durable scoped: some data will stand even longer than the code that created it. In order to be sure about its durability we need to store it in some disk based engine like Cassandra, Hadoop or S3.

Let's focus on state that should be stored for an undefined period of time.

Database as single source of state

Our next source of inspiration will be Making sense of Stream Processing ebook. Martin Kleppmann does a portrait of the increasing complexity when using a classic database as the Single Source of Truth, SSOT.

We said earlier that avoiding state as much as possible is a good idea. Avoiding is a misleading verb, so don't get the impression that a stateless service doesn't have to cope with state, it just delegates it to a data store, an expert on that non-functional domain (durability, isolation, consistency, replication...). Same with Serverless architectures, of course there is a server, but you don't have to operate it on that paradigm, you delegate it to experts.

Delegating our durable state to a database is a good idea then. However what happens when our system starts to slow down as the load increases? We could then decide to include a cache. Same happens if we need to have full text search capabilities and our DB is not able to cope with that efficiently. Suddenly, we have a SSOT, with at least two projections of that state, optimised for different query patterns. We have two options to keep those views of the state synchronised.

Database as backbone for data integration

As we said, databases are experts on their own domain. Data integration, with different sources and sinks, lands outside of that domain. We'd like to use the same code that we use for operational transformations (with the same testing and deployment processes) to integrate data. Let's see how we can solve this issue using application code.

Dual writes for data integration

With this approach, the application is now in charge of updating every single data store. This sounds like a good idea but it introduces a couple of issues.

- Race conditions: if two clients send updates onto the same logical record, there is no guarantee that those updates will be applied ordered into the different datastores. Isolation, from ACID properties, helps you with this concurrency problem, and implementing it at service level has some complexities.

- Coupling: suddenly, what was a simple app that writes to a database, it's a monster with coupling with different datastores. This approach doesn't scale organisationally as the owners of that service will have to serve requests for every single team.

- Crash recovery: even in the absence of concurrency this approach has an issue with Atomicity from ACID properties. What happens if the first update succeed but the last one fails? It's not feasible to provide distributed heterogenous transactions, so, again, the app will have to provide a do-it-yourself implementation of transactions.

Reflections on derived state

Before reaching to the proposed solution, let's think deeply about the concept of SSOT and derived data. Why do we keep different views of the original data? Let's see the reasoning behind different examples:

Materialised views: our SSOT will have a format that won't satisfy every single query pattern. Maybe it's a normalised relational database as we need to save on storage costs and we were looking for strong referential constraints. We might have a multi-joins query that takes a lot of time, so we decided to persist that view in the database, to speed up reads. Database will take care of updating the materialised view as soon as the original tables gets updated.

Indexes: every table, column family or whatever data store abstraction, provides an efficient way of accessing its data. Maybe that's not enough for our query patterns, so we'll need to provide an index. Again, the database will be in charge of updating it.

Caches: some part of our data will be accessed more often. Also, there are physical storages that are faster and more expensive. We use caches to keep 'popular' data, 'hot' and available by storing them in spare data storage.

Replicas: our state is the core of our business. We can't afford losing any data or being unavailable. The best way to protect ourselves from data corruption/loss or unavailable nodes is replicating our data to different locations.

What is the state of our system? The original or the derived data. As long as the derived data has durability and consistency guarantees, they're a valid view of the state of the system at a given instant in time. What is the data structure used by databases to implement those derived forms? The answer is The Log. As we agreed that we want to use different data sources, specialised in their own non-functional domains, we could learn and use the lessons of The Log in order to provide reliable views of the state of our system.

The Log

Last inspiration for this post is I heart logs from Jay Kreps. We've already covered Kafka in this blog, and today we'll see how Kafka, as an implementation of the log abstraction, will help us to sync the derived forms of our state.

A log is a data structure that holds an ordered set of messages. That order is really important for distributed systems, as we saw before. Kafka provides a publish-subscribe implementation around concepts like topic, partition, broker or consumer. The idea is simple, the log becomes the central point of integration. No datastores will talk directly with each other, either the original producer will have to handle itself the data integration.

Let's go through the ACID properties to see how Kafka can help us to implement an scalable and easy to understand distributed solution:

- Atomicity: what happens if one of the consumers of the log has a problem and can't write to the cache or search engine? Every consumer keeps a pointer, offset in Kafka's terminology, to the last successfully consumed message in the log. Whenever the consumer is available again, can consume those messages and finish the transaction. We could say that is eventually atomic, and that's enough for most of distributed systems.

- Isolation: the problem of race conditions has to do with the absence of order. The order guarantees that the log provides, solves this issue.

- Durability: Kafka has some strong durability guarantees. Messages are written to disk and replicated into several brokers, however, we should not use Kafka as a long term store. Backing up messages into S3 or Hadoop is the usual approach.

- Consistency: consumers can have different data ingestion rates when consuming from the log. That's an awesome property as it decouples producers and consumers, using the log as a buffer. However that implies that the state of our system will be eventually consistent, as the processing is asynchronous. That's again usually enough for plenty of use cases, but it presents a problem when the update can set up the system in a wrong state. The log will be still a useful data structure for providing an ordered and scalable data structure, but we will need to check if the new update holds the state constraints of our system against one of our queryable datastores.

Summary of state at system level

One useful image for visualising state, is a position of memory holding a integer. That integer will be updated from time to time, and if we want to not lose updates, that position will need to be locked or synchronised causing some contention.

This model offers some problems when we provide derived views of that state. Now, we need to synchronise over the network, and that's been proven as a complex, unreliable and not scalable task.

The alternative is stop contending for positions of memory. Instead of updating values, let's keep a history, a changelog, of everything that happens into that logical record. That's called event sourcing in Domain driven design, and it's a powerful idea that has been used as a low level detail of implementation by many databases.

Conclusion

I hope that after reading this post, you agree with me that Simplicity and Scalability goes together when handling state. Immutability is a powerful idea that is changing the way that we develop software. Tracking what happened, instead of just the final snapshot of those events, gives business flexibility and insights to improve their products. At the same time makes developers and sysadmins lives much easier, as that history of state gives info about why and how a system works.

Thank you for your time, feel free to send your queries and comments to felipefzdz.

Related Blogs

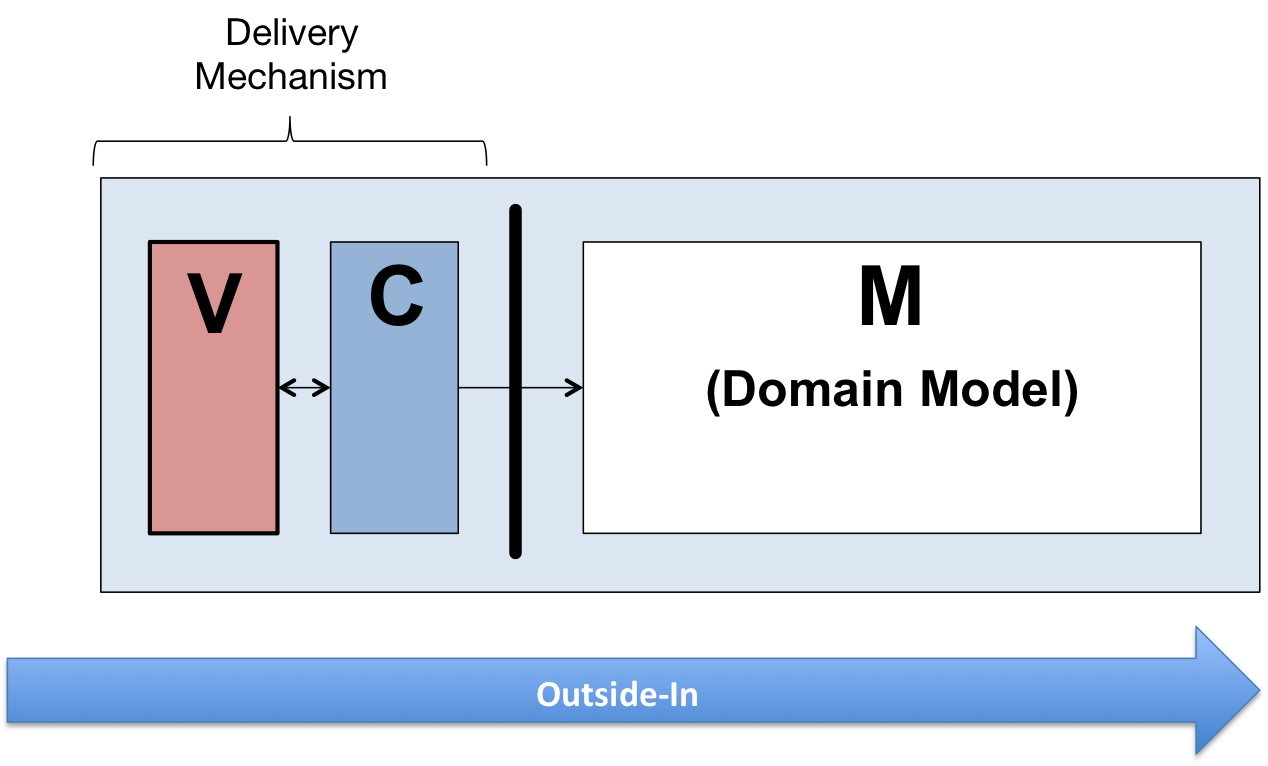

- By Sandro Mancuso

- ·

- Posted 23 Oct 2017

A Case for Outside-In Development

- By Tom Spencer

- ·

- Posted 25 Sep 2020

How do I streamline a path to production?

Get content like this straight to your inbox!

Software is our passion.

We are software craftspeople. We build well-crafted software for our clients, we help developers to get better at their craft through training, coaching and mentoring, and we help companies get better at delivering software.

Latest Blogs

Software Modernisation and Employee Retention...

Becoming PCI Compliant

Codurance signs the Microsoft Partner...

Useful Links

Contact Us

London, EC1M 5PU

Phone: +44 207 4902967

2 Mount Street

Manchester, M2 5WQ

Phone: +44 161 302 6795

Carrer de Pallars 99, 4th floor, room 41

Barcelona, 08018

Phone: +34 937 82 28 82

Email: hello@codurance.com