Richard Wild

See author's bio and postsFirst steps.

In the previous article, we introduced functional programming from first principles. It was a lot of verbiage and no practice. The idea of programming without side effects is all well and good, but we need to know how to actually do it. So let’s explore it by looking at some code. The roman numerals kata is a good exercise that we can use to illustrate these ideas.

Roman numerals.

Briefly explained, the roman numerals are a number system that represents numbers using letters from the latin alphabet: the number one is represented by I, five by V, ten by X, fifty by L, one hundred by C, five hundred by D, and one thousand by M. The rules are:

- When numerals appear to the left of numerals of lower or equal value, the values are added, so II is two, III three, and VI is six.

- When a lower-value numeral appears to the left of a higher-value one, the lower value is subtracted from the higher value. Therefore IV is four, IX is nine, and XL is forty.

Both rules apply simultaneously in any given number, so:

- XIV is 14, i.e. 10 + (5 - 1)

- LIX is 59, i.e. 50 + (10 - 1)

- CXL is 140, i.e. 100 + (50 - 10).

Armed with this knowledge, we can write a specification in Groovy for converting hindu-arabic numbers to roman numerals:

class NumeralsShould extends Specification {

def "convert arabic numbers to roman"(int arabic, String roman) {

def numerals = new Numerals()

expect:

numerals.convert(arabic) == roman

where:

arabic | roman

1 | "I"

2 | "II"

3 | "III"

4 | "IV"

5 | "V"

6 | "VI"

9 | "IX"

27 | "XXVII"

48 | "XLVIII"

59 | "LIX"

93 | "XCIII"

141 | "CXLI"

163 | "CLXIII"

402 | "CDII"

575 | "DLXXV"

911 | "CMXI"

1024 | "MXXIV"

3000 | "MMM"

}

}

The key to tackling this exercise is to eliminate the special cases by treating the subtractive pairs as numerals in their own right, i.e. CM is nine hundred, CD is four hundred, XC is ninety, XL is forty, IX is nine and IV is four. When you do this, the problem becomes purely additive. You end up with a set of symbols that may assembled into a valid roman numeral and thus summed to equal any natural number:

class Numerals {

def getNumerals() {

return [

[symbol: 'M', value: 1000],

[symbol: 'CM', value: 900],

[symbol: 'D', value: 500],

[symbol: 'CD', value: 400],

[symbol: 'C', value: 100],

[symbol: 'XC', value: 90],

[symbol: 'L', value: 50],

[symbol: 'XL', value: 40],

[symbol: 'X', value: 10],

[symbol: 'IX', value: 9],

[symbol: 'V', value: 5],

[symbol: 'IV', value: 4],

[symbol: 'I', value: 1],

]

}

String convert(int number) { ... }

}

There is more than one way to implement this kata, but probably the most obvious is to run down the symbols in descending order of value. While the current symbol value is less than or equal to the number, repeatedly append the symbol to the output and subtract the value from the number; otherwise move on to the next symbol. Keep repeating until you subtract the number away to zero. The string of symbols you have appended together is your result:

class Numerals {

def getNumerals() { ... }

String convert(int number) {

String roman = ''

numerals.each { numeral ->

while (number >= numeral.value) {

roman = roman.concat(numeral.symbol)

number -= numeral.value

}

}

roman

}

}

This code is okay, but is it functional? According to the first definition I gave in part one, it is:

In functional code, the output value of a function depends only on the arguments that are passed to the function, so calling a function f twice with the same value for an argument x produces the same result f(x) each time.

That is certainly true of this function: given a certain input, it always returns the same value. It does not alter any state outside its own scope, nor does it depend on any state outside its own scope that may be altered by any other thread. (That is why I implemented a method to create the map of symbols on demand). It meets the criteria for a pure function.

But is it written in a functional style? Not at all. There may be no global state but there is internal state, and it is certainly being modified. It concatenates strings to build up the result, and it repeatedly subtracts from the input number. It even modifies its parameter, which many programmers will object to even if they are otherwise comfortable with mutating state. Overall, the algorithm is highly imperative in nature:

- Create an empty string.

- Do these things while the number is greater or equal to the symbol value.

- Append the numeral to the string.

- Subtract from the number.

So how can we rewrite this code to be less imperative? In particular, how do we implement iteration without re-assigning anything? In our loop, there are three things that need to be kept track of:

- The iteration counter (ok, the for loop handles this for us implicitly so we can pretend that one isn’t there).

- The string of output numerals.

- The result of the subtraction.

To iterate is human; to recurse, divine.

The answer is we use recursion. Let’s broach the subject with a simpler example. This function counts down from a given number:

void countDown(int from) {

for (var i = from; i > 0 ; i--)

System.out.println(i);

System.out.println("We have lift-off!");

}

The state being mutated in this function is the loop counter i. We can avoid mutating it by making the function invoke itself:

void countDown(int from) {

System.out.println(from);

if (from > 1)

countDown(from - 1);

else

System.out.println("We have lift-off!");

}

It behaves exactly the same, but now nothing gets re-assigned. The functional goodness here comes with two costs: firstly, a slight decrease in readability. The second cost we will come to shortly.

To rewrite our roman numerals function into a recursive algorithm, it will be easier if first we flatten the nested loops into a single loop like this:

class Numerals {

def getNumerals() { ... }

String convert(int number) {

def roman = ''

def numeralIndex = 0

while (number > 0) {

def numeral = numerals[numeralIndex]

if (number >= numeral.value) {

roman = roman.concat(numeral.symbol)

number -= numeral.value

} else {

numeralIndex += 1

}

}

roman

}

}

Yes, I agree this is not an improvement on the original, but now we can more easily refactor the function to use recursion:

class Numerals {

def getNumerals() { ... }

String convert(int number) {

convert(number, 0, '')

}

String convert(int remainder, int numeralIndex, String roman) {

if (remainder == 0)

roman

else {

def numeral = numerals[numeralIndex]

if (remainder >= numeral.value)

convert(remainder - numeral.value, numeralIndex, roman.concat(numeral.symbol))

else

convert(remainder, numeralIndex + 1, roman)

}

}

}

Unfortunately we had to overload the convert method, but we will overlook this matter for now. The overload takes a remainder, a numeral index and a string that accumulates the result. If the remainder is zero then the accumulated string already contains the result so we return it. Otherwise, we get the symbol and value at the given numeral index. If the value is less than or equal to the remainder, append the symbol to the result, subtract the value from the remainder and recurse. If the value is greater than the remainder, increment the numeral index and recurse.

Now we have an algorithm that does not re-assign the value of anything. It’s also much less imperative in nature. The only statement left in the code is the assignment

def numeral = numerals[numeralIndex]

and even that could be factored out if we wanted to.

But is it better this way? I would not say so, personally: the original version was shorter, clearer, and did not need an overload for the convert function. Let’s do an experiment and see how it looks in a functional language. Using Brian Marick’s testing library Midje we can write a set of facts in Clojure:

(facts "roman numbers"

(fact "roman numeral for given arabic number"

(convert 1) => "I"

(convert 2) => "II"

(convert 3) => "III"

(convert 4) => "IV"

(convert 5) => "V"

(convert 6) => "VI"

(convert 9) => "IX"

(convert 27) => "XXVII"

(convert 48) => "XLVIII"

(convert 59) => "LIX"

(convert 93) => "XCIII"

(convert 141) => "CXLI"

(convert 163) => "CLXIII"

(convert 402) => "CDII"

(convert 575) => "DLXXV"

(convert 911) => "CMXI"

(convert 1024) => "MXXIV"

Not very different so far. The equivalent implementation in Clojure looks like this:

(def numerals

[["M" 1000] ["CM" 900] ["D" 500] ["CD" 400]

["C" 100] ["XC" 90] ["L" 50] ["XL" 40]

["X" 10] ["IX" 9] ["V" 5] ["IV" 4]

["I" 1]])

(defn convert

([number]

(convert number 0 ""))

([remainder numeral-index roman]

(if (zero? remainder)

roman

(let [[symbol value] (nth numerals numeral-index)]

(if (>= remainder value)

(convert (- remainder value) numeral-index (str roman symbol))

(convert remainder (inc numeral-index) roman))))))

If you’re not familiar with Lisp then it may look a little weird, but Lisp syntax is in fact absurdly simple. In most languages a call to function f passing arguments x and y looks like this: f(x, y). To turn it into Lisp, simply delete the commas and move the open paren left of the function name: (f x y). That’s pretty much all of Lisp learned already. Like the Groovy version, the Clojure code overloads the convert function, accepting either a single parameter [number] or three parameters [remainder numeral-index roman]. The meanings of the parameters are the same as in the Groovy.

The if form in Clojure is an expression, identical in operation to the ternary operator in C-style languages:

(if cond value-when-true value-when-false)

The cond expression evaluates to a value, and any value in Clojure can be treated as truthy or falsey; nil and false are falsey and everything else is truthy. This style of programming with expressions rather than statements results in the build-up of close parens at line endings, which many people find objectionable about Lisp. Haskell avoids the issue by dispensing with the parentheses. Clojure has a couple of macros that ameliorate the problem too, but we will come to that later.

The only part of that Clojure code that is slightly magical is this part:

let [[symbol value] (nth numerals numeral-index)]

The meaning of (nth numerals numeral-index) should be obvious: it gives you the nth element from the numerals vector where n is equal to numeral-index. That will be a vector of two elements, e.g. ["M" 1000]. We use the Clojure feature called destructuring to assign symbol to the first element in the vector (“M”) and value to the second (1000).

Apart from personal taste, there is little to choose between the two versions. The main difference is that functional languages inexorably lead you to recursion by the design choices made in the language itself. In Groovy you have the option to use a loop. In an imperative language you would always choose looping over recursion, if an iterative algorithm is possible, because it performs better. This is the second cost I mentioned earlier, and it’s a biggie.

Tail call elimination.

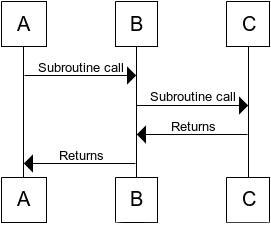

Whenever you write a recursive program you must have some idea beforehand how deep the recursion will go, lest you blow the stack. A program that jumps to a subroutine pushes the return address on the stack, to be popped when the subroutine completes. If that subroutine calls another subroutine, then it pushes its own return address on top. The stack holds all the return addresses in the correct order so that the program is always able to return control back to where it came from. Obviously, the greater the depth of nesting in your subroutines, the more stack space is required. In non-recursive code this is no problem: you’d never get near the depth of nesting needed to run out of memory. But recursive subroutines call themselves! In functional programming, recursion is the method of choice for doing iteration, but this makes the prospect of blowing the stack very realistic.

This problem can be avoided. The key is to position the subroutine calls so that they are in tail position. This means that there are no more instructions between the return of control from the subroutine, and the end of the routine that called it. In other words, when subroutine A calls subroutine B from tail position, control returns from B only to return immediately to the caller of A. Let’s illustrate this with some code. Consider the stupid countdown example from earlier:

void countDown(int from) {

System.out.println(from);

if (from > 1)

countDown(from - 1);

else

System.out.println("We have lift-off!");

}

The recursive call to countDown is in tail position, because when it returns there is nothing more to do in the calling function. So let’s consider a recursive call that is not in tail position:

private long factorial(long n) {

if (n == 1)

return n;

else

return n * (factorial(n - 1));

}

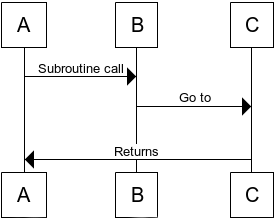

The recursive call to factorial is not in tail position, because its result must be multiplied with n to calculate the return value for the outer function call. But why does this matter? It matters because, as Guy L. Steele observed in a paper to the ACM in 1977, a subroutine call in tail position can be replaced with a goto. Unlike a subroutine call, a goto does not anticipate control returning to the calling routine, so no return address is pushed on the call stack.

We can show Steele’s observation with a diagram showing two nested subroutine calls:

Here, routine A calls subroutine B, and then B calls subroutine C. When finished, C pops the return address off the call stack to return to B, and B pops the previous return address to return to A.

But, as Steele noticed, if the call to C is in tail position then B may as well go to C directly, leaving its own return address on top of the call stack, because C will pop that address and return directly to A. This is what we wanted to happen anyway. This is called tail call elimination and the benefit is twofold: firstly, we’ve avoided one unnecessary jump instruction, and much more importantly, we’ve avoided growing the call stack.

If you eliminate tail calls this way in a recursive algorithm, you get a routine that repeatedly jumps to its entry point until the terminating condition is achieved. In machine terms this is no different to a regular loop!

Ah, but there is a catch. You need to be programming in a language that performs this kind of optimisation. The .NET runtime does, under certain circumstances. The JVM does not. Functional languages that run on the JVM must therefore provide workarounds. Scala will optimise tail-recursive functions into loops when possible, and you can verify that it is doing so by annotating functions you want to receive this treatment with @tailrec. (The compiler will generate an error if a @tailrec annotated function is not, in fact, tail recursive). Clojure provides the loop..recur form which also rewrites your code into a loop while giving you the ‘feel’ of recursion:

(defn convert [number]

(loop [remainder number, numeral-index 0, roman ""]

(if (zero? remainder)

roman

(let [[symbol value] (nth numerals numeral-index)]

(if (>= remainder value)

(recur (- remainder value) numeral-index (str roman symbol))

(recur remainder (inc numeral-index) roman))))))

This also enables us to get rid of the overload, which only existed to support the recursion. If we refer back to the original Groovy version of this code, I think the functional code is no more complex than the original, and somewhat more elegant:

String convert(int number) {

String roman = ''

numerals.each { numeral ->

while (number >= numeral.value) {

roman = roman.concat numeral.symbol

number -= numeral.value

}

}

roman

}

Referential transparency.

Before we wrap up, cast your mind back to this version we had of the roman numerals code in Groovy:

class Numerals {

def getNumerals() { ... }

String convert(int number) {

convert(number, 0, '')

}

String convert(int remainder, int numeralIndex, String roman) {

if (remainder == 0)

roman

else {

def numeral = numerals[numeralIndex]

if (remainder >= numeral.value)

convert(remainder - numeral.value, numeralIndex, roman.concat(numeral.symbol))

else

convert(remainder, numeralIndex + 1, roman)

}

}

}

We can calculate the roman representation of 14 by plugging values in directly for the remainder, numeralIndex and roman arguments. I have cheated a little bit by setting the argument index to 8; I did that to skip straight over the numerals with higher value. Otherwise, this exercise, which is already quite long-winded, would become considerably longer:

String convert() {

convert(14, 8, '')

}

There is a property of pure functions, as the convert(int, int, String) method is, that we are able to copy the implementation straight over its invocation, like this:

String convert() {

if (14 == 0)

''

else {

if (14 >= 10)

convert(14 - 10, 8, ''.concat('X'))

else

convert(14, 8 + 1, '')

}

}

This property of pure functions is called referential transparency. I have also copied literal values over numeral.value and numeral.symbol because they were being looked up from an array by a literal index value, therefore this simplification was possible. Now, some of the paths through that code are guaranteed not to be taken: 14 is clearly not equal to 0 and it is clearly greater than 10. So we can manually delete all the branches that are guaranteed not to be taken, and the code reduces down to this:

String convert() {

convert(14 - 10, 8, ''.concat('X'))

}

Now we can replace the convert method invocation again:

String convert() {

if ((14 - 10) == 0)

''.concat('X')

else {

if ((14 - 10) >= 10)

convert((14 - 10) - 10, 8, ''.concat('X').concat('X'))

else

convert((14 - 10), 8 + 1, ''.concat('X'))

}

}

Once again we can delete all the branches that are guaranteed not to be taken, and this time it reduces down to this:

String convert() {

convert((14 - 10), 8 + 1, ''.concat('X'))

}

Let’s do the replacement again. This time we replace numeral.value with 9 and numeral.symbol with 'IX':

String convert() {

if ((14 - 10) == 0)

''.concat('X')

else {

if ((14 - 10) >= 9)

convert((14 - 10) - 9, (8 + 1), ''.concat('X').concat('IX'))

else

convert((14 - 10), (8 + 1) + 1, ''.concat('X'))

}

}

Again we can see with our eyes which branches are guaranteed to be taken, so we can reduce the code down to this:

String convert() {

convert((14 - 10), (8 + 1) + 1, ''.concat('X'))

}

and replace the method invocation yet again, this time replacing numeral.value with 5 and numeral.symbol with 'V':

String convert() {

if ((14 - 10) == 0)

''.concat('X')

else {

if ((14 - 10) >= 5)

convert((14 - 10) - 5, ((8 + 1) + 1), ''.concat('X').concat('V'))

else

convert((14 - 10), ((8 + 1) + 1) + 1, ''.concat('X'))

}

}

Once again we eliminate all the branches guaranteed not to be taken and we obtain:

String convert() {

convert((14 - 10), ((8 + 1) + 1) + 1, ''.concat('X'))

}

We replace the method invocation once again, substituting 4 for numeral.value with and 'IV' for numeral.symbol:

String convert() {

if ((14 - 10) == 0)

''.concat('X')

else {

if ((14 - 10) >= 4)

convert((14 - 10) - 4, (((8 + 1) + 1) + 1), ''.concat('X').concat('IV'))

else

convert((14 - 10), (((8 + 1) + 1) + 1) + 1, ''.concat('X'))

}

}

And this time eliminating the branches not taken results in this:

String convert() {

convert((14 - 10) - 4, (((8 + 1) + 1) + 1), ''.concat('X').concat('IV'))

}

For the very last time, we copy over the method invocation:

String convert() {

if (((14 - 10) - 4) == 0)

''.concat('X').concat('IV')

else {

if (((14 - 10) - 4) >= 4)

convert(((14 - 10) - 4) - 4, (((8 + 1) + 1) + 1), ''.concat('X').concat('IV').concat('IV'))

else

convert(((14 - 10) - 4), (((8 + 1) + 1) + 1) + 1, ''.concat('X').concat('IV'))

}

}

and because (((14 - 10) - 4) == 0) is true, we can see that the final result is:

String convert() {

''.concat('X').concat('IV')

}

which yields XIV, fourteen.

In the previous article I said that programming without ever re-assigning the value of a symbol could lead to an explosion in the number of symbols. At least it seems that it should. But this process of repeatedly replacing a function call with its implementation, although very laborious, did not result in an increase in the number of symbols used in the program.

Are you recommending we should program this way?

Not at all. When I'm programming in an imperative language, I still use iteration over recursion. If you recall in part 1, I said that in each imperative language there is a certain sweet spot for FP. This is certainly not it. By no means does this article make a killer argument for functional programming, in fact by itself it doesn't make a case for FP at all. My purpose instead is to explain the fundamentals and demonstrate that programming without mutating state is indeed possible. I will try to explain why it is desirable later.

Next time:

If this was all there was to functional programming, I would forgive you for thinking it not worth the hype. Fortunately this is not all, by a long way. We have seen some functional programming here, but not what I would call the functional style. When you program in a functional style, you very rarely need to write loops of any kind. A loop is a means to an end, not an end in itself. The functional style lets you program more in terms of your desired ends, and bother less about the means to achieve them. In the next article I will begin to broach this subject. We will introduce first-class functions and lambda expressions, and how their use can often avoid the need to write explicit loops at all.

The whole series:

Get content like this straight to your inbox!

Software is our passion.

We are software craftspeople. We build well-crafted software for our clients, we help developers to get better at their craft through training, coaching and mentoring, and we help companies get better at delivering software.

Latest Blogs

Software Modernisation and Employee Retention...

Becoming PCI Compliant

Codurance signs the Microsoft Partner...

Useful Links

Contact Us

London, EC1M 5PU

Phone: +44 207 4902967

2 Mount Street

Manchester, M2 5WQ

Phone: +44 161 302 6795

Carrer de Pallars 99, 4th floor, room 41

Barcelona, 08018

Phone: +34 937 82 28 82

Email: hello@codurance.com