- Por Sandro Mancuso

- ·

- Publicado 06 May 2015

Developers across many organisations adopted code reviews as one of their core practices. Although that sounds like a very reasonable thing to do, over time the goal that led to the adoption of the practice is forgotten and the only thing left is the mindless application of the practice itself.

Maintain quality. Disseminate knowledge. Avoid serious bugs in production. Maintain consistence in the design and architecture of the software. All very compelling and logical answers, no doubt, but if those are the goals, is code review the most efficient way to achieve them?

It’s difficult to discuss a practice like code review without understanding more about the context in which it is applied. How often is it done? Before or after the code is merged? How many people are involved? What’s the size of the team? Do you have distributed teams? What’s the average size of the code being reviewed? A couple of classes with a few lines each or a few classes with hundreds of lines each? Is the code only related to a small part of the domain or it touches multiple areas of your application? Do people have the power to reject the code being reviewed? How many people have this power? Team leads? Architects? Whole team, including junior developers? What happens when the code is rejected? Is the code base being changed by developers from the same organisation or is an open source project that may accept contributions from developers all over the world, who don’t know each other, and have little accountability for their changes? What do you look for in a code review? Finding bugs? Lack of consistency? Small details like variable names? Big architectural violations? Compliance with non-functional requirements? Bad design? Does the team even agree on what bad/good design means?

Knowing the answers to these questions are extremely important in order to decide if code review (and how it is done) is actually the best way to achieve our goals.

Well, code review is a practice and can’t be blamed if the code being reviewed sucks completely. Code review cannot be blamed if you have chosen to review a huge chunk of code weeks after it was merged. What may be painful is the way you decided to do code reviews and not the practice itself.

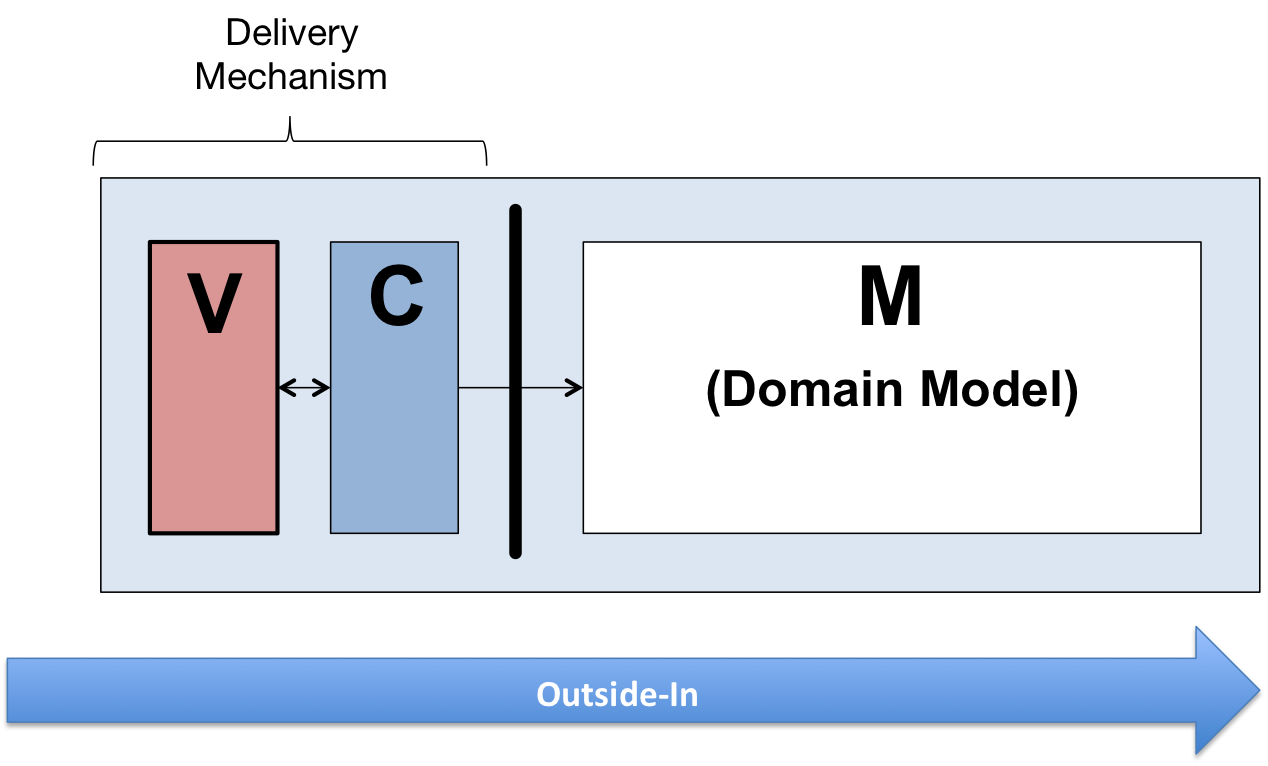

Before it is merged into production: We work in pairs and with very short-lived small branches (approximately 2 hours of coding and very few classes changed). Pairs raise a pull requests (an average of 2 to 5 per day) and another pair reviews their code. Since we work in very small increments, reviews, although often, are very easy and quick to do. Code is rarely rejected and when it is, it is very easy and quick to fix. This way we avoid a lot of re-work and decrease the chances of accumulating technical debt.

Disseminate knowledge and avoid unnecessary work: Having pairs reviewing each other’s code helps to disseminate knowledge of different parts of the system and also avoid that certain pairs do unnecessary work.

Verify if there are bugs: I find this pointless. We have tests for it. Code is only reviewed after all tests pass. Tests are part of the code review though.

After the code is merged into production: That is too late. What do we do if we find that the code is not good enough? If the code is already written, it’s working, it’s in production, and won’t be changed anytime soon, why review it and change it? I would wait to change it if I ever need to work on it.

When the code being reviewed is too large: Reviewing large changes are painful and disrespectful. In my last company, we decided as a team that we would reject large changes. The pair of developers would need to break that change in smaller changes and commit them bit by bit so the reviewer could make sense of it. That was also used to teach them a lesson. Only small commits would be reviewed and merged into production. Period.

Check for code standards: I normally use Java and we have plenty of static analysis tools that are executed during our builds. If the code doesn’t comply with the bare minimum of quality defined (by the team) in these tools, the build fails. No code is reviewed if the branch build is failing.

There are other situations where I would or wouldn’t use code reviews but those are the most important ones.

Code reviews are quick and cheap to do when you work in small increments, in pairs, and constantly rotate pairs. As domain and technical knowledge are quickly spread across the team, code reviews become more a mechanism of knowledge sharing than actually a quality gate. Pairing give us a much quicker feedback loop and helps to minimise many mistakes. In our experience, code written by a pair has a much higher chance to be accepted in a code review than when it is written by a single developer.

Many problems during code reviews can be avoided when we have a good team culture. Practices without goals are pointless. Before choosing a practice, figure out exactly what you want to achieve and only then choose practices that will help you with that. Practices can not be blindly adopted. In order for them to work, you need to have the right context and mindset. Otherwise you run into the risk of blaming the practices for your own deficiencies.

Software es nuestra pasión.

Somos Software Craftspeople. Construimos software bien elaborado para nuestros clientes, ayudamos a los/as desarrolladores/as a mejorar en su oficio a través de la formación, la orientación y la tutoría. Ayudamos a las empresas a mejorar en la distribución de software.