Sandro Mancuso

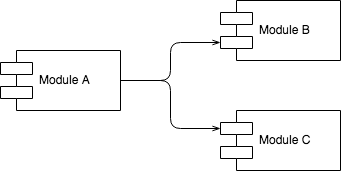

See author's bio and postsThere is no reason to have a backend when there is no front-end. There is no reason to have an API when there is no one to consume it. There is no reason to have a class when there is no other class (or framework) to use it. There is no reason to have a method when there is no one calling it.

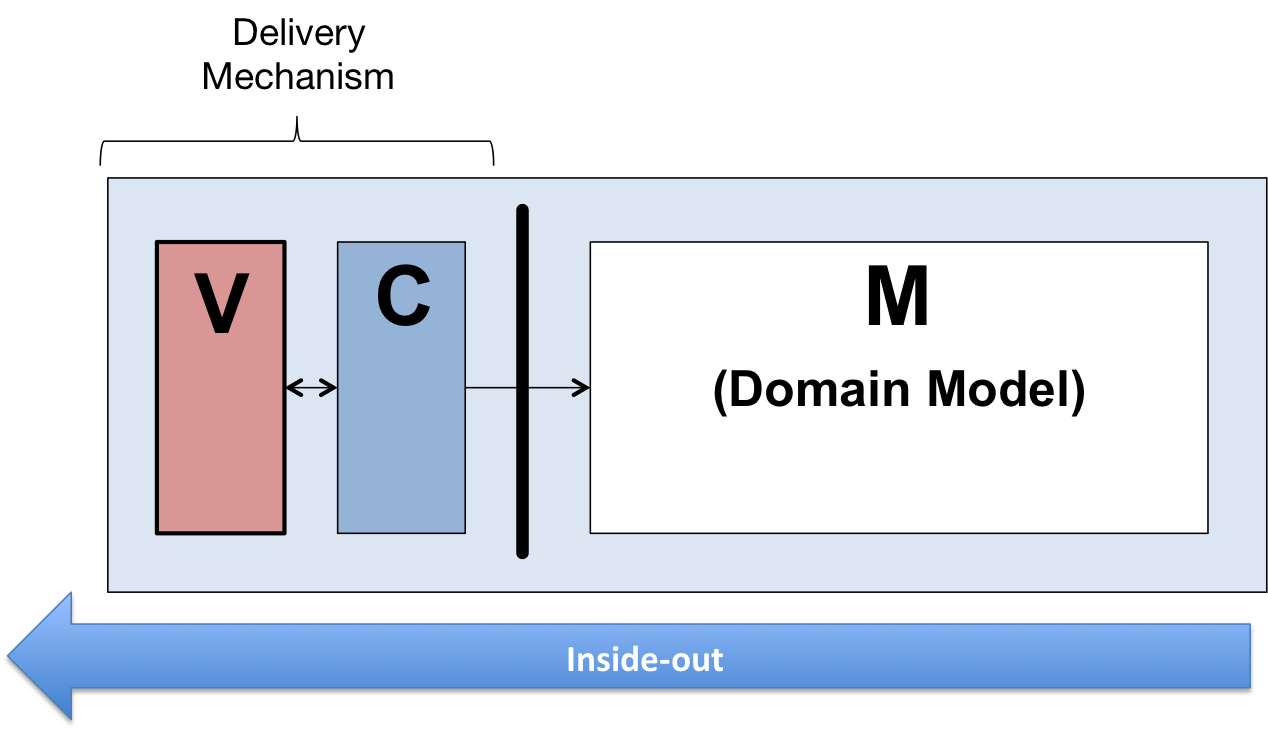

Inside-Out Development

Many developers focus on implementing the Domain Model before defining how it is going to be used by the external world. The way users (via User Interface) or other systems (via APIs, Messages) interact with the system is treated as a lesser concern. Doing business analyses and focusing on modelling the domain first is what I have learned at university over two decades ago. That is also what I learned with my seniors during the first half of my career. Led by the belief that the front-end changes more often than the business rules, we opted for creating a fully decoupled and robust backend system first, leaving the UI to a later stage. This approach is what I call inside-out development.

Advantages

Let’s look at some of the most important advantages of inside-out development:

Early validation of business requirements

Some questions related to the business requirements only emerge when we start working on the code. Start coding from the domain model allows us to focus on the business rules straightaway, giving us an opportunity to uncover business inconsistencies, clarify requirements with more details, and validate assumptions. Getting a quick feedback on important areas of the system is a risk mitigation strategy.

Risk mitigation

Investigative and preventive work that allow developers to uncover problems that can significantly change their understanding of the scope and cost of the project before investing too much in the solution. Identifying and mitigating risks before building too much code minimises re-work and helps to keep the cost of the project down.

Most valuable things first

Developers should work on the most valuable tasks first and there is a common belief that the domain model is arguably the most valuable piece of software. A counter argument to that is that software has no business value if it is not used by anyone. From this perspective, the domain model only has value when the full feature is implemented and used in production.

Volatile User Interface left to the end

User Interfaces are notorious to be volatile while business rules tend to change far less once they are defined. Starting with the business rules first allows backend developers to make some progress while front-end developers iterate on the UI design.

Disadvantages

Let’s look at some of the disadvantages of this approach:

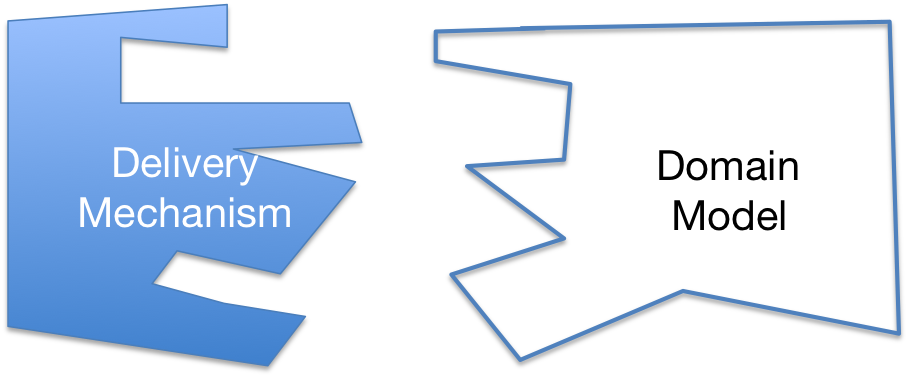

Wasted effort

Without the guidance of a well-defined and concrete need from the external world (being a user interface or API — delivery mechanism), we can easily build things that are not needed. When we finally define the delivery mechanism and try to plug it in, we quickly realise that the backend does not exactly satisfies all the needs of the delivery mechanism. At this point we need to either write some plumbing code to connect both sides, change the backend or worse, compromise on the usability defined by the delivery mechanism so that we can reuse the code in the backend as is.

Speculative development

When focusing on the internals of a system before defining how the system is going to be used, our imagination runs wild. We start thinking about all the different possibilities and the things our code should do. We try to make our domain model as robust and generic as possible. We want to explore and often go off on a tangent without realising it — “I think our application will need this behaviour because it fits in my domain model”. The more we speculate, the more accidental complexity creeps in.

Delayed feedback

Users or external systems consuming our APIs don’t care about our backend. We can only get feedback from them if we can provide something for them to use or access. It doesn’t matter what we do on the backend. If the user journey (via the user interface) or APIs are not suitable, our backend has no value. If the front-end or APIs are done after the domain model (backend), we will only get feedback when the whole feature is done and that is too late.

Coarse-grained development

A great way to deliver software incrementally is to slice our features in thin vertical slices. This becomes very hard when we start from the domain model, as we are not writing code to satisfy a specific external need. Vertical slices should be guided by outside requirements and we won’t have them if we start building the domain model first.

Without being able to find a proper thin vertical slice, we need to wait for the whole feature to be done in order to get feedback and deploy. It is also difficult to predict when a feature will be done when the deliver mechanism is treated as an afterthought.

Rushed delivery mechanism

Another danger of focusing on the backend first is that when the backend is done, developers are generally out of time or not so keen to work on the front-end. They end up rushing the front-end implementation causing two main problems: a) a bad user experience, b) lower quality standards when comparing to the backend, leading to a messy and difficult-to-maintain delivery mechanism.

Impaired collaboration

Mobile, front-end and backend teams should not work in parallel while the APIs are not defined. This is also true for cross-functional teams where mobile, front-end and backend developers are in the same team.1 Having backend developers defining APIs cause a lot of friction and re-work once mobile and front-end developers try to integrate their code.

A deeper look at the advantages of Inside-Out

Let’s take a deeper look into the advantages of Inside-Out development and check if they are real advantages and if some of them can be applied to Outside-In development as well.

Risk mitigation

One of the biggest advantages of Inside-Out Development is to tackle the core of the system first and hopefully uncover unknown problems — this is called risk mitigation. But is risk mitigation a thing we should only do in Inside-Out Development? Are all types of risk mitigation and exploratory work at the same level?

Quite often we are not sure what the solution for a given business requirement should look like, how the business requirements should be designed, which tools we should use, or how some frameworks work. Some exploratory work is needed.2

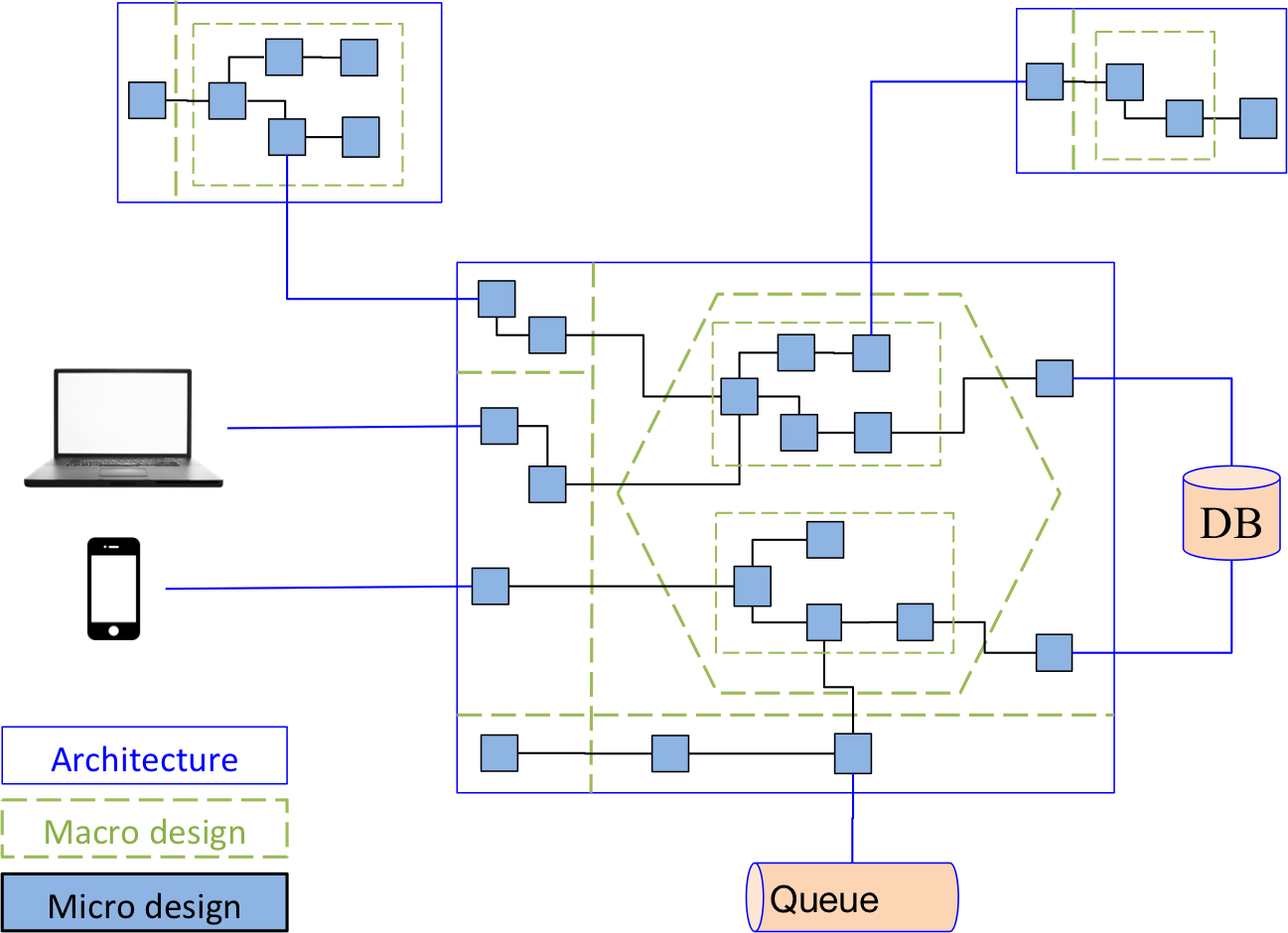

Let’s look at some categories of exploratory work:

- Technical: Related to frameworks, libraries, databases, or tools.

- Architecture: Related to how systems will talk to each other, how logic is distributed across systems, APIs, messages between systems, production environments, logging, monitoring, etc.

- Macro-design: Related to the organisation of code at high level: layers, hexagonal, bounded contexts, etc.

- Micro-design: Related to business domain rules, class collaborations, algorithms, function compositions, etc.

There is a difference between trying to uncover unknowns as early as possible and actually delivering a feature. They should not be part of the same task. Whenever we are unsure about what needs to be done or how things should work, we should create a spike (or any other time-boxed activity) to investigate the problem. Once we have more information we can then commit to build a feature.

Do not mix exploratory work with feature development.

Among the four categories above, I find there is value to create separate spikes for Technical, Architecture, and Macro Design investigations but not so much for Micro Design. That’s an area of my code that naturally emerge through Outside-In TDD. Discovery at micro design level normally have far less impact in the project than discovery at higher levels. That means that focusing on up-front design at micro level is normally a waste of time, but the same is not true for the other levels.

User Interface changes and impacts

Another argument to start development from the domain model (Inside-Out) is that the user interface (UI) is volatile and its implementation should be done after the domain model is finished. Well, it is often true that the UI changes more often than the business rules do, but do all the UI changes really impact the backend? Let’s have a look at the most common types of UI changes and their respective impact on the backend code:

Aesthetic

Aesthetic changes are related to the look and feel of the UI — normally done by web designers, front-end developers and user experience specialists without any impact in the backend. Aesthetic changes are normally the most common type of changes in the UI.

Behavioural

Behavioural changes are related to how users interact with the system. They impact the user journey, the steps users need to perform to achieve a desired outcome.

Behavioural changes can be subdivided in two types of changes: Navigational and Actionable.

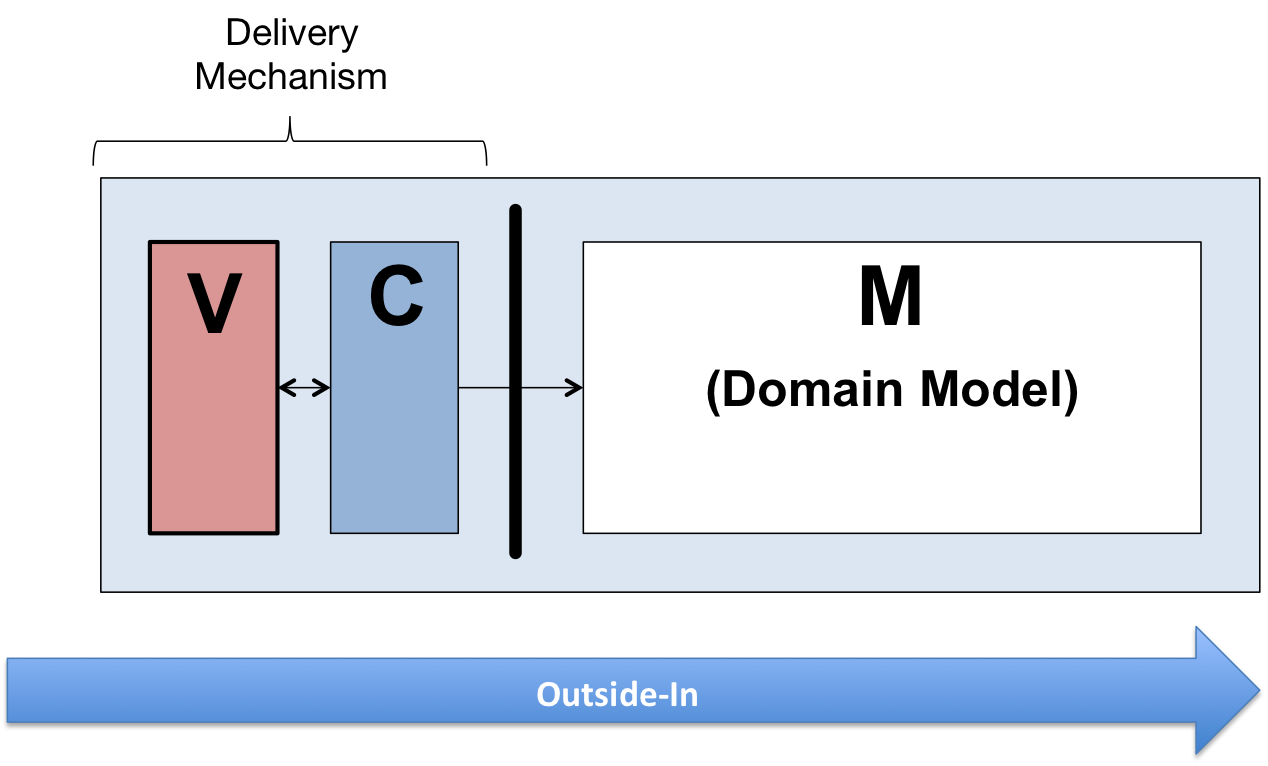

Navigational Navigational changes are related to how a user navigates across the application or within specific user journeys. In a web application, navigational changes in the UI may or may not impact the backend. It all depends on the type of front-end technologies being used and how the View and Controller layers (MVC) are structured. If the Controller layer lives in the browser (normally the case when using frameworks like AngularJS and React), there is no change in the backend. If we have a more traditional web application where the Controller lives in the backend, then the backend needs to change every time a link (or button) is added, removed, of changed. For more details, please have a look at my previous post on MVC, Delivery Mechanism and Domain Model.

Actionable Actionable changes are related to the actions the user can perform in the system. They are the ones that provide the business value to the user and to the company. Examples would be buying products, reading reviews of restaurants, booking a ticket, just to mention a few. Most often, the changes in the UI are small — adding a button, changing URL parameters, HTTP method or return code. Actionable changes in the UI are directly related to changes in the backend, as it normally impacts the API and possibly the flow triggered by it.

Data

Data changes are related to the data displayed to the user or required from user. These changes involve a change in the data the existing APIs receive or return. The impact on the backend varies according to the data and the complexity to return or store the required data.

How much do UI changes really impact the domain model?

As discussed before, the way we decide to structure our delivery mechanism and domain model will make our backend more or less susceptible to UI changes. In a well-structured web application, changes in the backend can be significantly reduced if the delivery mechanism is fully responsible for the navigation of the system while the domain model is only exposing business flows and managing data. Although designed to satisfy user’s needs, the domain model should have no knowledge of how those business flows are presented to users.

User interactions represent user needs

Every user interaction with the user interface represents a user need. It is the systems’ job to satisfy the user’s need every time the user requests something. If the user only wants to navigate from one part of the website to another, than this logic belongs to the delivery mechanism and not the domain model. However, if the user wants store or retrieve information, than the logic belongs to the domain model.

A case for Outside-In development

In order to agree on how we should design software, we should first agree with a few basic principles. For the rest of the post I’ll assume we all agree with the following:

- Value is only delivered when the system is in production and satisfactorily used.

- We should strive to deliver value as soon and as often as possible.

- We should do the appropriate due diligence before building anything.

- We should get feedback as soon and as often as possible.

- We should always work in small and valuable increments.

- We should keep things as simple as possible, but no simpler.

- We should only build what really needs to be built, nothing more.

- We should not work on technical tasks if they do not have business value.

- Investigative work should be time-boxed and done as separate a task.

Outside-In Development

Outside-In development is an approach that focuses on building just enough well-engineered code to satisfy an external need, reducing accidental complexity by removing speculative work.

Code should only be written to satisfy an external need, being from a user, an external system, or another piece of code.

Note: For the rest of the post I will assume people are working on a cross-functional team.3

Incremental development

We should only build what really needs to be built, nothing more.

Without constraints our imagination runs wildly. And so does over-engineering. While building software it is important to be constrained by (or focused on) the bare minimum that needs to be done to satisfy a business requirement.

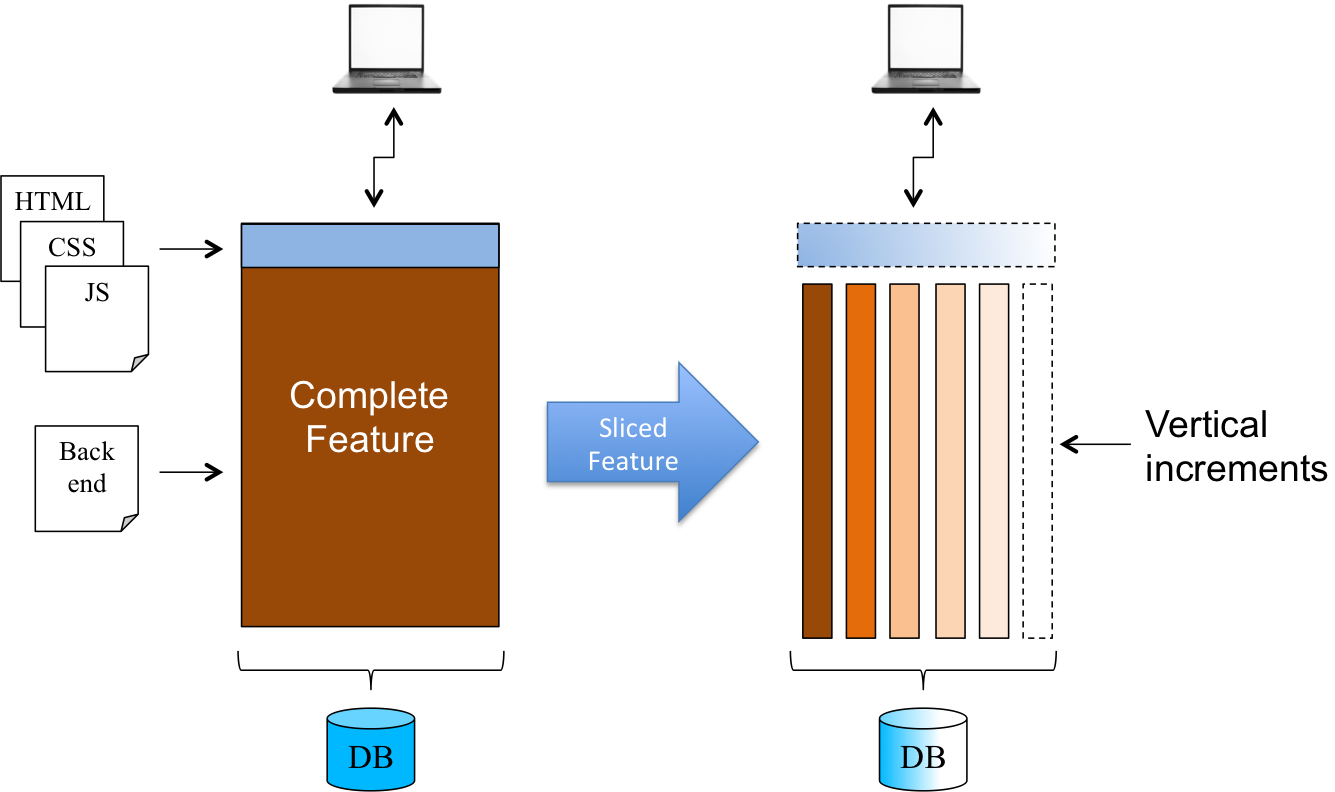

In Outside-in development, instead of working on the domain model first and then the persistence and UI, only releasing to production when the whole feature is done, we prefer to work in small increments and drive the development from the UI.

Drawing mock-ups

The first thing to do is to quickly draw a few mock-ups using a tool like Balsamiq. The cool thing about Balsamiq is that we can quickly create executable mock-ups, that means, we can run the mock-ups, clicking on links, moving to other pages, etc. This activity is normally done in collaboration with users and/or Product Owners. While drawing the mock-ups we focus more on the user journey and the information we will have on each page, without wasting time on how the page will actually look. As we add names to the visual components (labels, forms, buttons, links, etc.), we have the domain language (or ubiquitous language) naturally emerging from those mock-ups. From the mock-ups we can extract all the nouns and verbs that will make up the vocabulary used in our domain model.

When mock-ups are done collaboratively, the whole team builds a clear vision of what needs to be done and also have full buy-in. Mock-ups give the whole team a better idea of how the system will be used and how features connect to each other. It’s also very easy and quick to try out ideas and play with different scenarios. Mock-ups become a good starting point to discuss user stories and start slicing the features into small deliverables without loosing sight of the whole.

A danger with this approach is to go too far with the mock-ups, trying to make them look like the real UI or create mock-ups for too many features. We should also never use mock-ups tools to generate code. The goal of having mock-ups is to agree on the user journeys and the data the users will be interacting with during each journey.

Breaking a feature into smaller increments

When starting a new feature, the first thing to do is to build the UI for that feature. That sounds very counter-intuitive and generally makes backend developers shake their heads. “Oh no, no, no. This is really wrong.” Well, is it? Building the UI will give us a very quick feedback from our users or Product Owner. If they don’t like how the system is going to be used or the language used, we can change it easily without any backend impact - there is no backend yet. Once we all agree with the UI, we will know the exact behaviour the backend will need to provide and will have a more well-defined and stable domain language. If the UI has behaviour, the whole UI can be tested independently, mocking the calls to the backend. This will also help to stabilise the APIs needed by the UI.

Once the UI is done, we are ready to slice the backend work in vertical increments. Each vertical increment should start from a user interaction and contain all the logic (persistence, communication with external systems, etc.) needed to satisfy that user interaction. Once this increment is finished, the system will have a new behaviour added to it.

This methodical approach to slicing our features in small increments and always start the development from outside (UI) allows us to easily define the boundaries for acceptance tests and use them to guide our development.

Once one increment is done, demoed and accepted, we can deploy it to production or any other environment.4 Now we are ready to start a new increment.

Outside-In API Design

But what if our application does’t have UI and only provide APIs?

APIs are also a delivery mechanism (from the domain model perspective) and the same Outside-In principle applies. APIs should always be designed to satisfy their clients’ needs. But before going deeper, let’s first have a look at different contexts where APIs are provided:

- Company-private APIs: Only used by systems controlled by the API provider (internal).

- Public APIs: Used by systems not controlled by the API provider (external).

- Hybrid APIs: Used by internal and external systems.

Company-private APIs

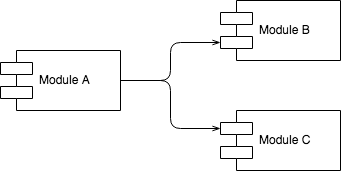

APIs sole purpose is to satisfy the needs of their clients, being web, mobile or other modules (services). Front-end, mobile, and backend developers should collaborate in API design. This collaboration should also happen when one team needs to consume an API being developed by another team. API design should be driven by the needs of the clients of the API and not by what backend developers think API clients will need.

I’ve seen in many companies, backend developers designing APIs and imposing them on mobile and front-end developers. Mobile and front-end developers often needed to adjust their user journeys or add a lot of unnecessary complexity because the APIs were not designed to serve them. This way of working became so common that many mobile and front-end developers now believe that API design is not part of their job and submissively wait for backend developers to tell them what the APIs are.

API providers (backend developers) should do everything in their power to reduce the work done by the clients of their APIs. Having APIs created by backend developers without clearly understanding the needs of the their clients and respective flows lead to complex delivery mechanisms and frictions between teams. The problems can be reduced significantly with cross-functional teams, where developers can collaboratively work on both sides of the application.

In case there is only one client for an API, the API should be specific for that client. APIs gradually become more generic as we add more clients and different external needs.

Public APIs

It’s difficult to predict all the possible ways a public API will be used. However, even public APIs should be designed with an external workflow in mind, starting with the most common workflow(s) that clients are expected to have while using our APIs. Depending on the type of APIs being exposed, we should start with a reference implementation and derive the API design from its needs. Reference implementations allow us to validate if flows and API granularity make sense.

We should reconsider our decision to expose an API if we cannot imagine a good use case for them.

Hybrid APIs

Hybrid APIs can be very complicated to maintain as they suffer pressure from different sides to evolve. Similar to the company-private and public APIs, they should also be designed according to the need of their clients. This scenario can be quite complicated and is out of the scope of this post.

Summary

Risk mitigation is an extremely important activity in any software project. We should not mix exploratory work with feature development.

Code should only be written to satisfy an external need, being from a user, an external system, or another piece of code. We should only build what really needs to be built, nothing more.

Guiding our design and code according to external needs helps us to remain focused on the task at hand and avoid speculative development.

Navigation is a delivery mechanism responsibility and backend should not change when navigation changes. The backend should only provide operations (actions) to the front-end.

In order to achieve continuous delivery and deployment, it is important work in small increments. Slicing features in small vertical slices is a great way to make sure each increment has business value.

Outside-In development is a structured and incremental way to deliver software, focus on delivering just enough behaviour to satisfy an external need.

Note: In the next blog posts we will dive into more details of Outside-In development.

-

Cross-functional team does not mean cross-functional people. ↩

-

For the sake of brevity I’m only referring to technical exploratory work, leaving out things like usability tests, business impact, etc.↩

-

Teams where among their members they have all the skills needed to build what they are asked. E.g.: front-end, mobile, backend, operations, etc.↩

-

Some times we might want to batch increments before deploying to production. Alternatively, we can continuously deploy them and use feature toggles. ↩

Blogs relacionados

- Por Matt Belcher

- ·

- Publicado 09 Jun 2020

Signs Your Software is Rotting

- Por Sandro Mancuso

- ·

- Publicado 26 May 2018

Should we always use TDD to design?

Get content like this straight to your inbox!

Software es nuestra pasión.

Somos Software Craftspeople. Construimos software bien elaborado para nuestros clientes, ayudamos a los/as desarrolladores/as a mejorar en su oficio a través de la formación, la orientación y la tutoría. Ayudamos a las empresas a mejorar en la distribución de software.

Últimos posts del blog

Codurance announces official Novoda Partnership...

Signs Your Software is Rotting...

Five Ways to Lead Positive...

Useful Links

Contacto

Londres, EC1M 5PU

Teléfono: +44 207 4902967

2 Mount Street

Manchester, M2 5WQ

Teléfono: +44 161 302 6795

Carrer de Pallars 99, planta 4, sala 41

Barcelona, 08018

Teléfono: +34 937 82 28 82

Correo electrónico: hello@codurance.es