- Por Dan Cohen

- ·

- Publicado 13 Nov 2017

The theoretical background for this experiment is available here: Tetris AI Experiment 1 & 2

As before, the source code is available on github

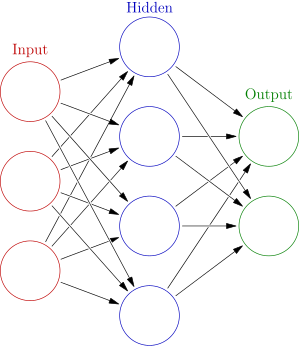

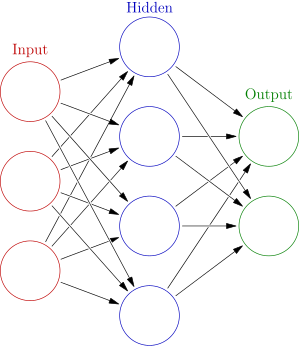

Since my last experiment, I have implemented crossover - AKA a 2 parent evolutionary algorithm. I have also tried changing the network structure to have 2 smaller hidden layers instead of 1 large one. The hypothesis was that this would allow more complex structures and concepts to be understood by the network. Both of these approaches have failed and that has led me to conclude that this model is a failure. A network like this is not well suited to Tetris.

My new plan involves a search tree and a Q-Learning process using a neural network as the state evaluator. This blog post may miss some technical details and may not explain everything regarding future plans. The following blog post with my implementation will have much more detail. The focus of this post is the failed experiment and the concepts involved in the next steps.

My goal in this experiment has been to achieve a bot that can play Tetris indefinitely. Given how quickly each decision is made and how fast the game clock runs, if a bot can survive for more than a second, I would consider that to be effectively sustainable.

I ran 3 different experiments attempting to get a functional Tetris bot. They all failed and my final conclusion is that a fully connected neural network making decisions about individual moves is not the appropriate strategy for a Tetris playing AI.

My initial hypothesis was that the network wasn't evolving usefully because each network would generate different traits and clusters of understanding, but because they were unable to share them, the variation alone would not be enough to achieve results. I implemented crossover with multiple crossover points and a chance to make a crossover at any given point. Theoretically this will allow for knowledge to be shared, mixed and matched between individuals.

The graph plateaus at 1000 after a steep learning period between generations 200 and 400. The maximum never exceeds 50,000. 50,000 points is achieved by clearing at most 5 lines. There is no reason to think that these line clears were anything other than accidents.

The following hypothesis was that a single hidden layer could not unwrap the complexity of the 2d space of the Tetris board. I modified my implementation such that there were 2 hidden layers instead. Unfortunately, because my implementation in java was not optimized for space and because I am running my experiments on my home computer, 2 hidden layers each with 1000 nodes required more RAM than I had available. As such, I reduced the number of nodes in each hidden layer to 100. After reading around the subject, I had begun to believe that 1000 was overkill anyway.

This experiment ran for 6000 generations. It was able to run for many more generations because the hidden layers are much smaller and the size of the weight maps is quadratic with the size of the layer. So these 6000 generations took a comparable amount of time to the 1200 generations from the previous experiment with the larger hidden layer.

At first glance, this does seem to have been an improvement. But after the first 1,000 generations the improvements are very minimal and there was never a breakthrough.

I finally out of desparation tried to run the experiment for much longer. I ran the experiment for over a week. It completed almost 30,000 generations before I got home from holiday.

The experiment plateaued after roughly 10,000 generations with the maximum score achieved never excdeeding 70,000. The majority of the learning occured in the first 2,000 generations. This appears to be when the network learned to use all the space available to stack pieces. The following 8,000 generations appear to be optimisations to this strategy. Every single generation after the first handful had at least 1 individual who managed to clear at least one line. Unfortunately, this never seems to have been an intentional decision by a network as the ability to recognise line clearing opportunities was never promulgated through the population.

It is clear by this stage that the vast majority of the learning takes place in the first 2000 generations. This is the period during which the network learns to pack tetrominos into the grid space minimising the amount of empty space. This happens because I added a term to the fitness function which takes into account the amount of empty space on the grid. This was intended to encourage the network into a position where it could discover the line clearing rules of tetris. The networks I have built do seem to have become somewhat efficient at packing space. Able to spot gaps and roughly fill them in with the tetromino they are controlling.

These networks have shown the ability to maximise a fitness function, but to make the more complex leap to clearing lines and undestanding spatial structures it will need a different strategy.

Here is my overall plan

Now let's break it down.

The first big change is that the bot will no longer play individual moves. The bot will instead choose a final location for the current piece.

Each game will be made up of a series of states and the game will end when a new piece cannot be brought into the play area without colliding. In order to transition between states, the bot must make a decision about which move it should make.

On the Tetris board, there are 200 positions that can potentially be occupied. The bot will pass each of those positions into a rules evaluation engine which is able to validate whether that move is a legal final position for a piece. This is exclude all positions where the piece is floating, all positions where the piece is colliding with something and all positions which are impossible to arrive at using a sequence of legal moves.

Each of the remaining legal positions is then evaluated using a neural network.

In order to know whether one decision is preferable to another, we must have some way of evaluating a game state. This is a simplified version of how chess and go engines make their decisions. It is possible to write a handwritten function that is able to evaluate a board state but I have no desire to do that. I believe that given the spatial nature of a Tetris board state the most appropriate tool to use is a convolutional neural network. However a similar result may be achievable with a fully connected neural network.

In either case, a neural network will evaluate the board state and decide what in-game score it expects this boardstate to be able to achieve.

The position with the highest evaluation score will be selected by the bot. Then the bot will apply that move and progress to the next state.

In order for a network to accurately evaluate a board state, it must be training. The training will occur after the game has completed. The final score will be used for back propagation. The idea is that after every completed game the evaluator will be a little bit stronger and the decision making power of the bot will be a little bit better.

I expect this to work because the impact of each move is much greater. The old network was making decisions about the best path to take at the same time as trying to understand the larger game concepts. The new network will have a direct interface to the game concepts and the pathing will be discovered by the rules engine.

The first iteration will likely be done with a fully connected neural network. Because the game state is effectively a 10x20x1 tensor, it is small enough that a traditional neural network should be effective. If this fails however, a convolutional neural network can be implemented.

The reason I failed is because I didn't stop to think about what problem the network was really solving. The direct problem the old network was solving is "How do I get this piece out of the way?". The new network will be solving the problem "How do I understand the value of this position" and that can then be utilised by the bot.

Software es nuestra pasión.

Somos Software Craftspeople. Construimos software bien elaborado para nuestros clientes, ayudamos a los/as desarrolladores/as a mejorar en su oficio a través de la formación, la orientación y la tutoría. Ayudamos a las empresas a mejorar en la distribución de software.