Richard Wild

See author's bio and postsJava programmers habitually pepper their classes with “getters” and “setters,” and this practice is so ingrained that probably few ever question why they do so, or whether they should. Lately I have come think that it is better not to and I have begun avoiding it in the Java code that I write. In this blog post I will explain the reasons why. But first, a quick history lesson.

JavaBeans

Getters and setters originated in the JavaBeans specification which came out originally in late 1996, and was updated to version 1.01 in August 1997. The original idea was to enable the creation of objects that could be used like building blocks to compose applications out of. The idea went, a “user” might use some kind of builder tool to connect together and customize a set of JavaBeans components to act together as an application. For example, a button in an AWT application would be a bean (AWT was the precursor to the Java UI library Swing). Alternatively, some JavaBeans would be more like regular applications, which may then be composed together into compound documents, so a spreadsheet bean might be embedded inside a web page.

An object is a JavaBean when it adheres to the following conventions:

- It must have a zero-argument constructor which cannot fail.

- It has properties which are accessed and mutated via ‘getter’ and ‘setter’ methods.

- For any property of a bean called

Foothen the accessor method must be calledgetFoo. In the case of boolean properties, the getter may alternatively be calledisFoo. - The setter method for Foo must be called

setFoo. - A bean is not obliged to present both a getter and a setter for every property: a property with getter and no setter is read-only; a property with setter and no getter is write-only.

The specification describes many different use cases, but it is clear from the above description that JavaBeans were conceived of as objects with behaviour, not mere bags of data. The idea has faded into obscurity, but while JavaBeans have been largely forgotten, the idiom of getter and setter methods in Java has persisted.

The Metaphor is Wrong

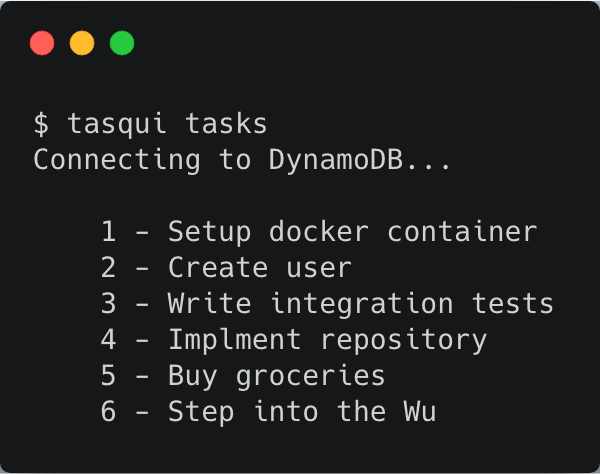

The concept of “get” and “set” seems natural enough, but is it correct? The JavaBeans convention uses “get” to mean query, which is an operation without side effects, but in the real world getting is an action that does alter state: if I get a book off the shelf, the book is no longer on the shelf. You may object that this is mere pedantry, but I think this misconception encourages us to think wrongly about the way we write our objects to interact with each other. For example, if we had a Thermometer class then most Java devs would write code to read the temperature like this:

Temperature t = thermometer.getTemperature();

Really though, is it the job of a thermometer to “get” the temperature? No! The job of a thermometer is to measure the temperature. Why do I labour this point? It is because “get” is an imperative statement: it is an instruction to the thermometer to do something. But we do not want to instruct the thermometer to do anything here; it is already doing its job (measuring the temperature) and we just want to know what its current reading is. The act of reading is done by us. Therefore the code is more natural when written this way:

Temperature t = thermometer.reading();

I think this better places the responsibilities where they really belong. But do always please give thought to whether the accessor is needed at all, because...

Objects Are Not Data Structures

The habit of writing classes with getters and setters has a subtle effect on the way we code. It naturalises the idea that we should reach into objects to get the data we need, process it, then update the objects with the results, rather than get the objects to perform the processing themselves. In other words, it encourages us to view objects as bags of data. We pull the data out through the getters and update them via the setters. The code that operates on the data, meanwhile, resides elsewhere.

If our coding habits incline us towards treating objects as mere data structures, ORM frameworks positively enforce it. Worse still, if you’re using Spring framework - and if you’re a Java dev there’s a good chance you are - by default it creates all your beans as singletons. (Confusingly, Spring beans have nothing to do with JavaBeans). So now you have a system composed of singleton objects, operating on data structures with no behaviour. If keeping your code and data separate sounds like a programming style you know, you’re not wrong: we call it procedural programming.

Consider whether this is a good thing. Java is, after all, supposed to be an object-oriented programming language. One of the great strengths of OO is that we can write classes of objects whose names and interactions reflect the problem domain. It enables us to write code that reads in terms of the problem being solved, without obscuring the big picture behind basic programming constructs and primitive data types. It helps us see the wood through the trees. We ought not to give this up.

What To Do Instead

Wherever possible, stop writing get and set! Sometimes it will be appropriate, but definitely stop using your IDE’s facility to generate getters and setters for you. This is just a convenient way to quickly do the wrong thing. If you need to expose an attribute on an object, simply name it after the attribute, but do also examine whether it’s really necessary to expose it. Ask why you want to do this. Can the task be delegated to the object itself? For example, say I have a class representing a currency amount, and I wish to sum a bunch of transactions:

Amount total = new Amount(transactions.stream()

.map(Transaction::getAmount)

.mapToDouble(Amount::getValue)

.sum());

Instead of the getValue accessor why not give the Amount class an add() method and have it do the summing for me?

Amount total = transactions.stream()

.map(Transaction::getAmount)

.reduce(Amount.ZERO, Amount::add);

This brings benefits - perhaps you raised an eyebrow at the idea of using a double to represent a currency amount. You'd be right, BigDecimal would be better. The second example makes this easier to fix because the internal representation is better encapsulated. We only need to change it in one place.

Maybe you want to get at an object’s data in order to test whether it is equal to something. In this case, consider implementing an equals() method on the object and have it test equality for you. If you’re using Mockito to create spies, this avoids the need to use argument captors: instead you can create an object of equal value to serve as an example and pass it directly to the verify statement for comparison.

There will be times when you must create accessors. For example, in order to persist data in a database you may need to access primitive representations of your data. Do you really have to follow the get/set naming convention though? If your answer is “that’s the way it’s done in Java,” I encourage you to go back and read the JavaBeans specification. Are you really writing a JavaBean to use it in the way the specification describes? Are you using a framework or library that expects your objects to follow the convention?

There will be fewer times when you must create mutators. Functional Programming is sweeping the industry like a craze right now, and the principle of immutable data is a good one. It should be applied to OO programs as well. If it is not necessary to change state, you should consider it necessary not to change state, so don't add a mutator method. When you write code that results in new state, wherever possible return new instances to represent the new state. For instance, the arithmetic methods on a BigDecimal instance do not alter its own value: they return new BigDecimal instances representing their results. We have enough memory and processing power nowadays to make programming this way feasible. And Spring framework does not require setter methods for dependency injection, it can inject via constructor arguments too. This approach is indeed the way the Spring documentation recommends.

Certain technologies do require classes to follow the JavaBeans convention. If you’re still writing JSP pages for your view layer, EL and JSTL expect response model objects to have getter methods. Libraries for serializing/deserializing objects to and from XML may require it. ORM frameworks may require it. When you are forced to write data structures for these reasons, I recommend you keep them hidden behind architectural boundaries. Don’t let these data structures masquerading as objects leak into your domain.

Conclusion

Speaking to programmers who work in other languages, I often hear them criticise Java. They say things like, “it’s too wordy,” or “there’s too much boilerplate.” Java certainly has its flaws, but when I enquire deeper into these criticisms I usually find they are aimed at certain practices rather than anything intrinsic to the language. Practices are not set in stone, they evolve over time and bad practices can be fixed. I think the indiscriminate use of get and set in Java is a bad practice and we will write better code if we give it up.

Blogs relacionados

Get content like this straight to your inbox!

Software es nuestra pasión.

Somos Software Craftspeople. Construimos software bien elaborado para nuestros clientes, ayudamos a los/as desarrolladores/as a mejorar en su oficio a través de la formación, la orientación y la tutoría. Ayudamos a las empresas a mejorar en la distribución de software.

Últimos posts del blog

Codurance announces official Novoda Partnership...

Signs Your Software is Rotting...

Five Ways to Lead Positive...

Useful Links

Contacto

Londres, EC1M 5PU

Teléfono: +44 207 4902967

2 Mount Street

Manchester, M2 5WQ

Teléfono: +44 161 302 6795

Carrer de Pallars 99, planta 4, sala 41

Barcelona, 08018

Teléfono: +34 937 82 28 82

Correo electrónico: hello@codurance.es