- Por Sandro Mancuso

- ·

- Publicado 06 May 2015

One of my best childhood memories is listening to the stories that my maternal grandfather, a very curious man, told me. However, not only do we lose a lot of details over time, but also we age and the same story can provide us different information after years. Last summer I reread Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe after more than 20 years and I discovered an absolutely different book.

Now I've had the same experience with The Mythical Man-Month by Fred Brooks, the father of the IBM System/360. This book was published in 1975 and it was reissued on its 20th Anniversary with four new chapters. On the one hand, it contains problems which still happen nowadays and it's worthwhile reading, because:

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. -- Jorge Santayana

On the other hand, it mentions concepts that I didn't realize for the first time I read it when I was studying in 1998. Here you'll find some of my notes about it.

The book starts talking about the craft of system programming and the joys and woes inherent in it. Among joys, we find: always learning.

When explaining the problems with the size of programs: That requires invention and craftsmanship. (...) So the first area of craftsmanship is in trading function for size. (...) The second area of craftsmanship is space-time trade-offs.

When talking about the need of paperwork in project management: To the new manager, fresh from operating as a craftsman himself, these seem an unmitigated nuisance, (...).

Let's remember this book was written in 1975 and terms like craftsmanship and craftsman were used.

Software projects suffered delays because of these reasons:

'All will go well', 'This time it will surely run', 'I just found the last bug', those thoughts sound familiar, don't they? I love the following sentence, because it's related to evolutionary designs: The incompletenesses and inconsistencies of our ideas become clear only during implementation.

This was the unit of effort used in estimating and scheduling. Men and months were interchanged, when confusing effort with progress. It's said that they can be only interchanged when a task can be partitioned among many workers with no communications among them and no sequential constraints.

Testing phase was the most mis-scheduled part of programming, because it was at the end of the development process. It was thought the solution was to increase the system test time in the original schedule.

When an omelette, promised in two minutes, has not set in two minutes, the customer has two choices: wait or eat it raw (or partially burned, when turning up the heat). Software managers might have the same courage and firmness as do chefs, avoiding false scheduling. We need to develop and publicize productivity figures, bug-incidence figures, estimating rules, and so on. The whole profession can only profit from sharing such data.

What does one do when an essential software project is behind schedule? Add manpower, naturally. The author shows several graphs which conclude in the Brooks's Law:

Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.

In 1991, Abdel-Hamid and Madnick studied this law in their book Software Project Dynamics: An Integrated Approach and they concluded:

Adding more people to a late project always makes it more costly, but it does not always cause it to be completed later. In particular, adding extra manpower early in the schedule is a much safer maneuver than adding it later, since the new people always have an immediate negative effect, which takes weeks to compensate.

Another study by Stutzke added a comment about the new people:

(They) must be team players willing to pitch in and work within the process, and not attempt to alter or improve the process itself!.

It was thought that the system might be the product of one mind. It was important to keep a conceptual integrity and one System Architect might design it all, from the top down. Ideas from implementers can break that integrity. However, the architect must always be prepared to show an implementation for any feature he describes, but he must not attempt to dictate the implementation.

Managers considered that senior people were too valuable to use for actual programming. On the other hand, management jobs carried higher prestige. To overcome this problem, Bell Labs abolished all job titles and there were only: member of the technical staff.

It was thought that managers needed to be sent to technical refresher courses, meanwhile senior technical people needed to be sent to management training. Only when talent permitted, senior people could manage groups (emotionally ready) and delight in building programs with their own hands (technically ready).

In the new chapters of the book (1995), fallacies about Waterfall model are included:

The author regretted the waterfall-oriented projects after most thoughtful practitioners had recognized its inadequacy and abandoned it. However, it took too long before that experience spread.

Nowadays, there is a trending goal replacing monoliths by microservices. However, in 1975, there were problems of space and costs and a more monolithic program was the solution, because it took less space.

In order to avoid bugs, the specification might be tested, before any code exists. In this way, developers wouldn't invent their way through the gaps and obscurities.

In 1971, Niklaus Wirth formalized a design procedure by a sequence of refinement steps:

From this process one identifies modules of solution or of data whose further refinement can proceed independently of other work.

The degree of this modularity determines the adaptability and changeability of the program.

It's said that a computer program is a message from a man to a machine. On the other hand, it tells its story to the human user, so documentation was important. In order to solve the problem with the maintenance of that documentation, they decided to write self-documenting programs:

The drawback of such an approach to documentation was the increase in the size of the source code that might be stored.

Brooks wrote that there was no silver bullet:

There is no single development, in either technology or management technique, which by itself promises even one order-of-magnitude improvement within a decade in productivity, in reliability, in simplicity.

Following Aristotle, he talked about two types of difficulties in software projects:

Brooks considered technical developments as potential silver bullets: high-level languages advances, OOP, Artificial Intelligence, Expert Systems, automatic programming, graphical programming, program verification (not error-proof programs, but meeting specification), environments, tools and workstations. On the other hand, he valued buy vs. build, requirements refinement and rapid prototyping, incremental development (growing, not building, software) and being great designers, because software construction is a creative process.

In 1971, Harlan Mills proposed that any software system should be grown by incremental development. That is, the system should first be made to run, even though it does nothing useful except call the proper set of dummy subprograms. Then, bit by bit it is fleshed out, with the subprograms in turn being developed into actions or calls to empty stubs in the level below.

It lends itself to early prototypes.

The morale effects are startling. Enthusiasm jumps when there is a running system, even a simple one.

One always has, at every stage in the process, a working system.

Rebuilding the development system every night and running the test cases were really hard, devoting a lot of resources, but they realized that it was rewarding, not only for discovering and fixing trouble as soon as possible, but also for the team morale and emotional state.

In 1971 and 1972, David Parnas wrote several articles about information-hiding concept.

In the Operating System/360 project, it was decided that all programmers should see all the material. That view contrasted with David Parnas's teaching that modules of code should be encapsulated with well-defined interfaces. Brooks recognized:

Parnas was right, and I was wrong. I am now convinced that information hiding, today often embodied in object-oriented programming, is the only way of raising the level of software design.

Parnas is also the author of the concept of designing a software product as a family of related products.

Brooks's experience with IBM Operating System/360 convinced him that:

(...) the quality of the people on a project, and their organization and management, are much more important factors in success than are the tools they use or the technical approaches they take.

In 1987, Tom DeMarco and Tim Lister published Peopleware: Productive Projects and Teams where they provide data about their Coding War Games and concluding things like:

The manager's function is not to make people work, it is to make it possible for people to work.

It reminds me of a post I wrote about my own concept of software quality, P3 Quality, in which People is the key factor.

In 1973, E. F. Schumacher published Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered proposing a theory of organizing enterprises with many semi-autonomous units, called quasi-firms, with a large amount of freedom, to give the greatest possible chance to creativity and entrepreneurship.

Brooks includes several examples of good results putting such organizational ideas into practice and how microcomputer revolution created hundreds of small start-up firms, marked by enthusiasm, freedom, and creativity.

In 1968, Melvin E. Conway published How do committees invent? where he related the organization chart with the first software design:

Organizations which design systems are constrained to produce systems which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.

And if the system design is to be free to change, the organization must be prepared to change.

A few days ago, I saw this tweet by Gregory Brown:

#Protip: If you want to make an observation or share a theory about Conway's Law... Mel is still around and actively doing his research.

— Practicing Developer (@practicingdev) March 16, 2018

Tag @conways_law and there's a chance he'll look at your stuff and comment. 😀

Also follow him. He's an incredibly insightful thinker.

Thanks to my friends Marc Villagrasa and Mike González, good and kind people, because I reread this book because of them. I hope I have been able to make it more enjoyable.

Software es nuestra pasión.

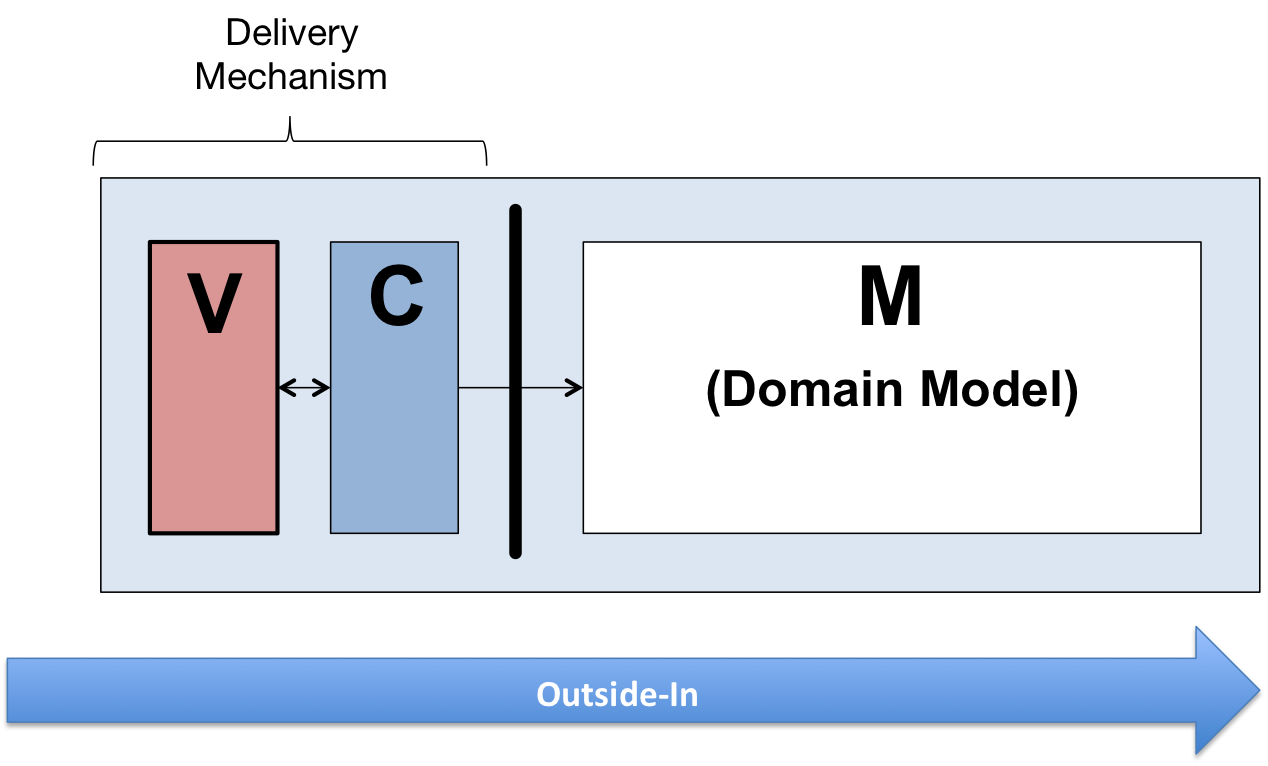

Somos Software Craftspeople. Construimos software bien elaborado para nuestros clientes, ayudamos a los/as desarrolladores/as a mejorar en su oficio a través de la formación, la orientación y la tutoría. Ayudamos a las empresas a mejorar en la distribución de software.