- Por Sandro Mancuso

- ·

- Publicado 23 Oct 2017

Mocking is still a point on contention among TDD practitioners. The biggest complaint is that when we use mocks the tests end up knowing too much about the internals of the module under test, making it difficult to refactor in the future. Because of that, a common recommendation is to avoid the use of mocks and only use them as an isolation mechanism in the following scenarios:

If we think about mocks as a testing tool, this is a very sound advice and most TDD practitioners would agree with that, including myself.

However, when building systems with a complex domain, where business flows are not linear (flows that touch different areas of the domain model and each area might trigger their own sub-flows), restricting the use of mocks to the boundaries described above is not enough.

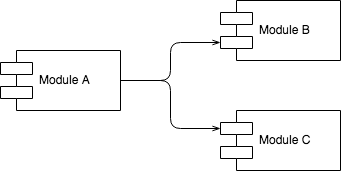

Let's look at the relationship between modules A, B and C.

Association

The diagram above describes that A is associated with B and C. By the direction of the association we can say that A uses B and C but B and C do not know A.

But are B and C part of A or just used by A?

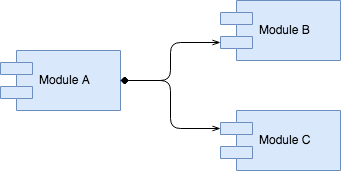

Composition

The diagram above describes that B and C are part of A, that means, their lifecycle is directly controlled by A's lifecycle. If A is removed (from memory or even from the code base), B and C are removed as well since they do not make any sense without A.

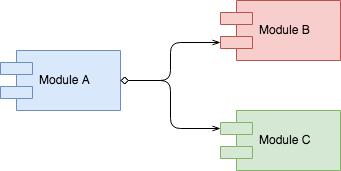

Aggregation

The diagram above describes that B and C are used by A, that means, their lifecycle is not controlled by A's lifecycle. If A is removed, B and C will continue to exist.

Both Composition and Aggregation are types of Association. This distinction is important as it may help us understand the boundaries of our modules or components.

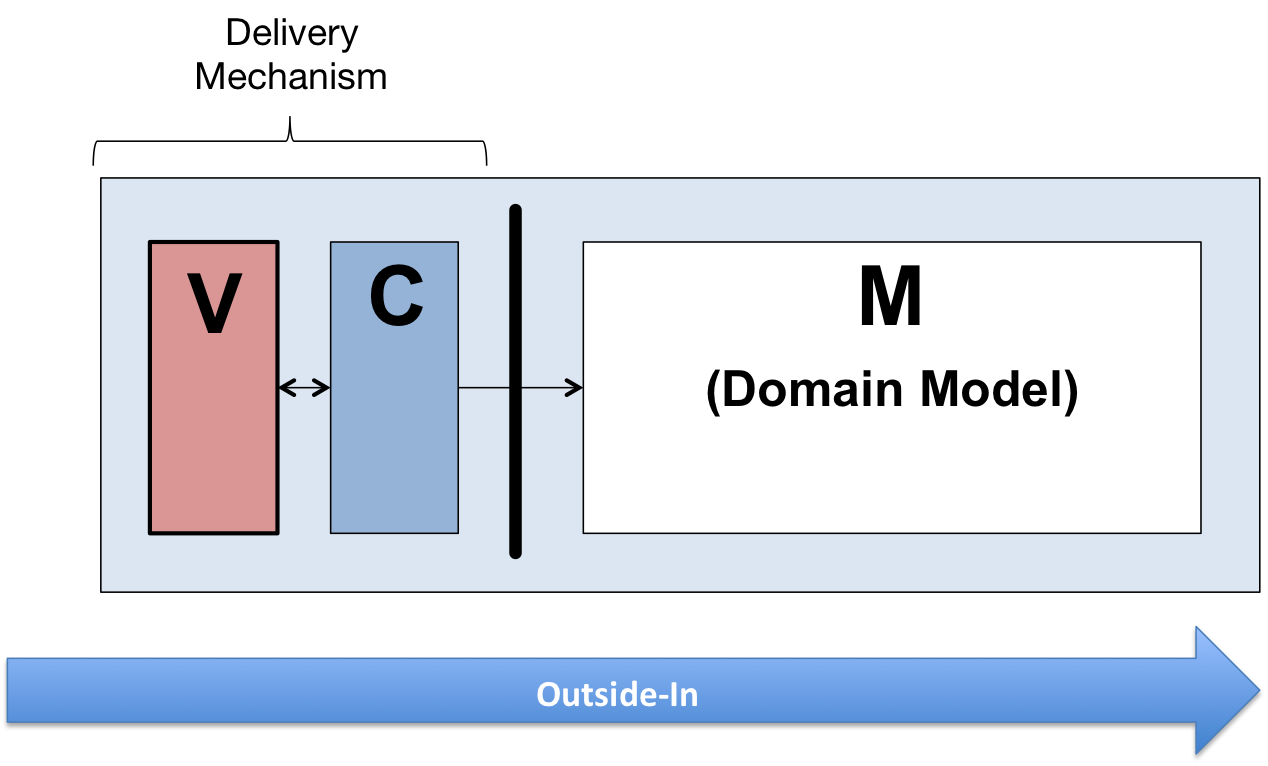

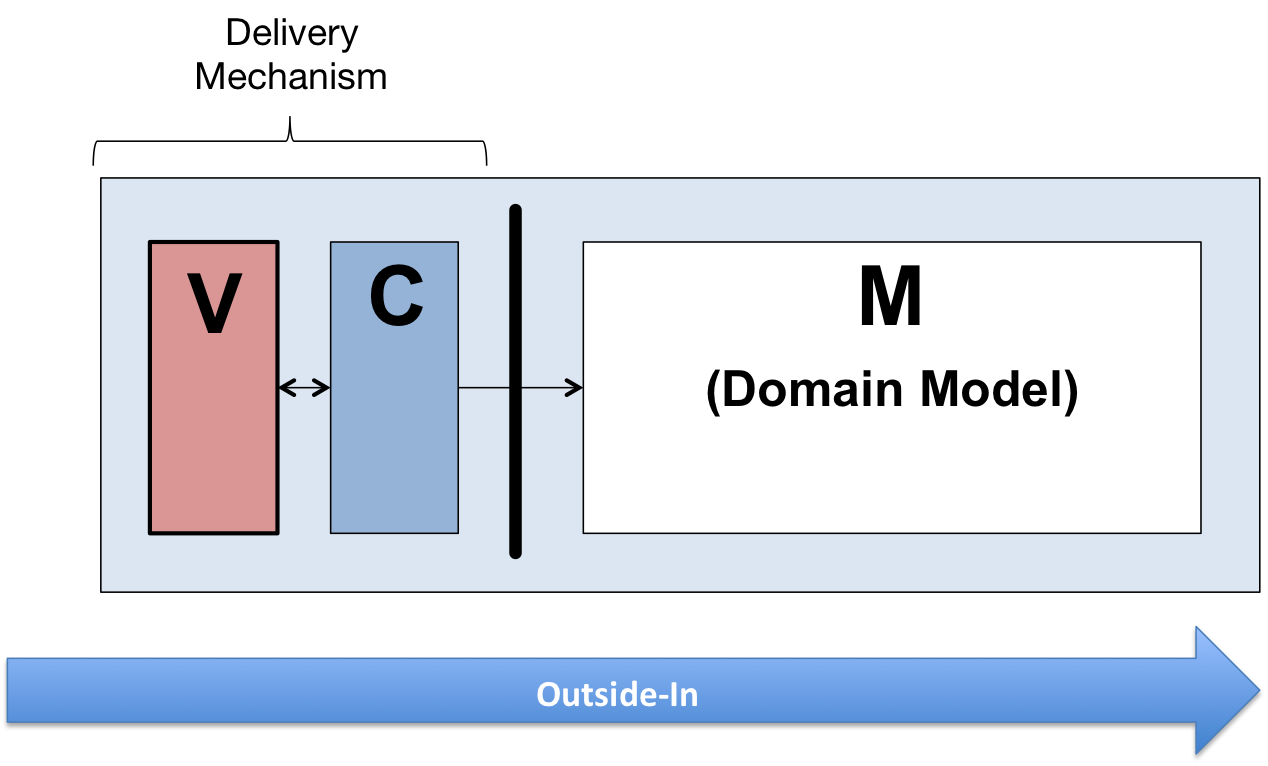

Before we talk about mocking we should talk about boundaries. Certain boundaries are very clear like packages, namespaces, classes, methods or functions. They are imposed by our programming language and paradigm. Other boundaries are more subjective, that means, they are defined by our macro design choices, like layers, hexagons, components, delivery mechanism, domain model, infrastructure, and design patterns in general. TDD practitioners, including the ones that normally do not like mocks, are happy to use mocks at the boundaries of whatever they are test-driving. The only problem is that they rarely agree where the boundaries should be drawn while test-driving their code.

Imagine we are building an e-commerce web application and after discussing with our Product Owner, we captured the following high-level requirements:

Scenario: Making a payment

In order to have my items delivered to my home address

As a buyer

I would like to pay for all items in my shopping basket

Acceptance criteria

We could add many more behaviours to the acceptance criteria, but I guess this is enough to use as an example of a feature (making a payment) where a single trigger from the browser can trigger a lot of behaviour.

To keep this post focused and simple, I'll only focus on the business logic described above and not go into the implementation details.

While reading the requirements above, I believe that it is clear that we will not try to put everything inside a single module. Because of that, test-driving all that logic in a Classicist approach seems to me a waste of time. The requirements above gives me enough information to make some macro design decisions and be more efficient while test-driving my code.

Looking at the requirements, we can identify two different types of flows:

Let's have a look at the potential modules and responsibilities:

The overarching logic also needs to be added to a module and this logic should be provided to the delivery mechanism.

When building a complex flow, with many movable parts, trying to build everything in one go can be extremely complicated as we need to keep alternating between logic at different levels of abstraction. E.g. We should not be focusing on details of fraud detection while test-driving the main business flow. That's when mocks can be very helpful as a design tool.

Mocking as a design tool makes more sense when using Outside-In TDD (London School). This TDD style focus on the decomposition of a big problem into smaller problems. It starts from the macro behaviour (main flow), decomposing it into smaller behaviours until the decomposed behaviours are small enough to be cohesive or have a single reason to change. In the example above, we would start test-driving the main flow first and only then think about the sub-flows inside the modules.

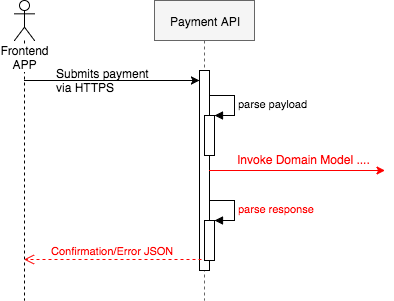

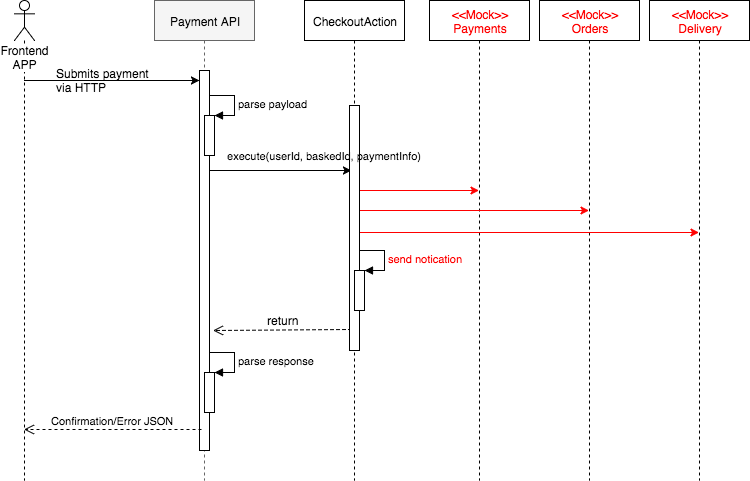

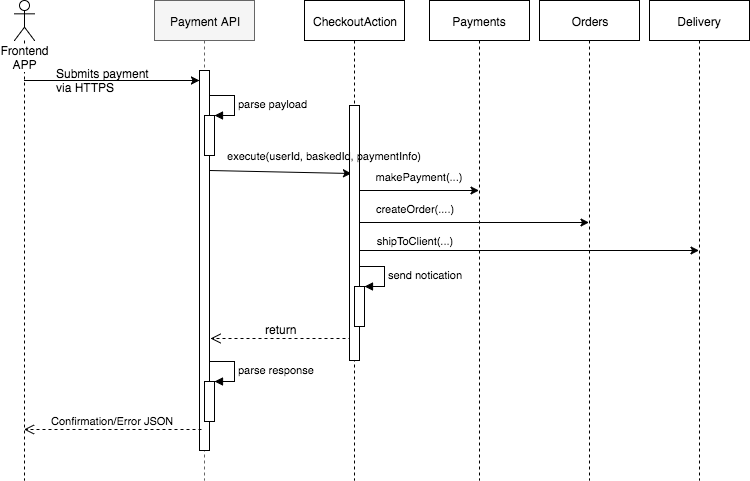

Let's say we will have an endpoint called PaymentsAPI that will parse the JSON received via HTTP request, will call the main flow, and will return the HTTP code and confirmation JSON to the frontend app.

Now we need to define the domain module that is going to be called by the PaymentsAPI. At this time, we can use a mock to design the interface of this module and finish the implementation of PaymentsAPI. The reason we could safely do this is that we already decided what behaviour will remain in the PaymentsAPI and what is going to be delegated.

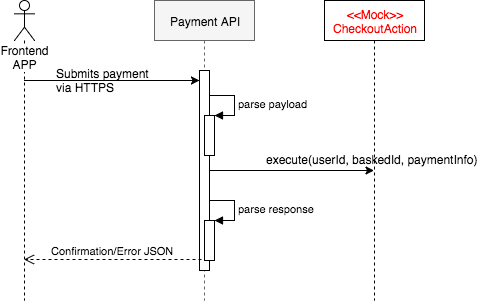

If you follow the Clean Architecture, Domain Driven Design, or Interaction Driven Design, we will need a module that will orchestrate the business flow. This module plays the role of a Use Case (Clean Architecture), Application Service (DDD) or Action (IDD). I'll use the IDD naming and call it CheckoutAction.

Using a mock to design the CheckoutAction public interface helped us to decide what the PaymentsAPI should send and what it would need to receive. This way we can finish testing the PaymentsAPI without worrying about the details of the business flow. This also allows us to hardcode some value and already test the whole user interface journey.

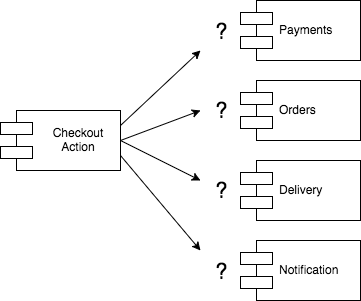

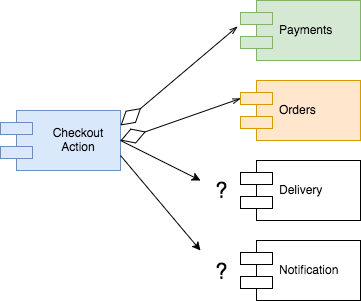

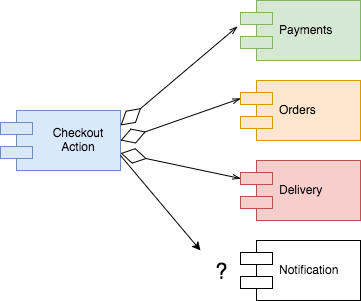

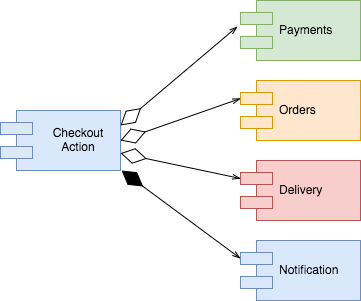

Now that we know that the CheckoutAction is the entry point to our domain model, we need to implement it. According to our previous analysis, we have at least four groups of behaviours that need to be orchestrated by CheckoutAction: Payments, Orders, Delivery, Notification.

When looking at the logic related to payments, orders, delivery or notification, how do they relate to the CheckoutAction?

Are they part of the CheckoutAction or used by it? This is an important distinction because the answer to this question directly impacts the boundaries we are drawing around our business components, which in turn will impact the testing strategy. Test-driving code is much easier when boundaries are well defined and a little upfront thinking can make TDD far more effective.

So, back to the question: How do we know if an association is a composition or an aggregation?

A simplistic approach would be to ask about lifecycles, that means, if we delete CheckoutAction, should we also delete the logic related to payments, orders, delivery and notification? We need to be very careful with this question because in theory, if the CheckoutAction is the only piece of code calling those other pieces of logic, they would be orphans and should be deleted. But that is not enough to decide if an association is an aggregation or composition. A better approach is to think about changeability. Do the modules change for the same reason? Are there different actors interested in them? Do they own different data? Should their change impact other areas?

Analysing changeability

First, let's discuss what should be the responsibility of CheckoutAction. If we try to put all the logic related to payments, orders, delivery, and notification plus the coordination across these areas, the CheckoutAction would be violate Single Responsibility Principle and probably a dozen of other design principles. To avoid this, we should leave the CheckoutAction control the main flow but delegate the behaviour of each step to their own modules.

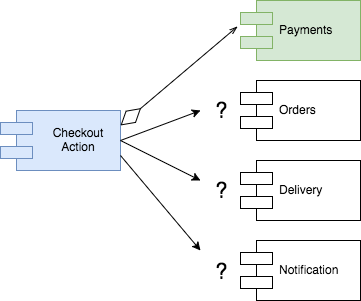

Now, let's look at Payments. We could add or remove payment methods, payment gateways, country specific logic, and fraud detection. Speaking to the business we discovered that before adding a new payment method or gateway to the platform, a different a group of people would get involved, sign contracts with providers, and these people are not the same ones that would be involved in other areas of the system. Should any of that impact the checkout flow? I would rather not have the changes in Payments affect the other areas. That would make the Payments module compatible with the Open/Closed Principle, that means, we could add or remove payment methods, gateways, etc, with no impact in the rest of the system. With that in mind, I'm quite confident to make the payments module totally independent from CheckoutAction, that means, an aggregation.

So, what about Orders? Speaking to the business we discovered that Orders have their own life cycle (new, waiting confirmation, paid, rejected, fulfilled, etc) and different parts of the system and internal users need orders information, mainly in the back office. This is enough information to make the decision of keeping Orders logic separate from the checkout process.

Delivery is a complex part of the domain as it involves different service providers in different parts of the world. They also charge different rates, have different contractual models, etc. Deciding which delivery options are available to users all over the world according to their delivery address is not a simple task. This information is maintained by a different back office team. It looks pretty safe to assume that Delivery should also be kept isolated from the rest of the checkout flow.

Finally we discuss the Notifications. The only thing we got from the business is that we would need to send an notification to the user with the result of the checkout process — either the payment has been received and the order recorded or the payment was rejected. Although I have a gut feel that this logic can grow and be reused, I don't have enough evidence of that, so in this case I'll keep it as a sub-module of the checkout process.

In order to gather the information above and decide what would be a composition or aggregation we only had to have a quick conversation with the product owner where we asked a few business questions about each part of the flow.

With the decision of what behaviour goes together (composition) and what behaviour is going to be in a separate module (aggregation), we just need to figure out how these modules are going to talk to each other.

At this point is when I use Outside-In TDD (London School) to test-drive the full implementation of CheckoutAction, using mocks to define the public interface of Payments, Orders, and Delivery. Their interface should be limited to the information that CheckoutAction needs, reducing coupling and increasing cohesion among modules.

Once CheckoutAction is fully implemented, we will also have defined the public interface of all its collaborators. The next step will be to think about the internals of each collaborator, knowing that nothing else will be impacted — as long as their public interface remain unchanged.

With three modules defined, we can now pick the first one, let's say Payments.makePayment(...) and explore. We can ask questions like: Shall we keep the logic for credit card, Paypal and Direct Debit isolated from each other? Shall we keep the fraud detection logic isolated from the payment methods? If we are storing credit card data, should he have a separate service and reduce the scope of the system that needs to be PCI compliant? Shall we have an area of the system where we decide which payment gateway we are going to use according to the location of the user? Answering these questions lead us to decide how many sub-modules Payments will have and the type of association among them - composition or aggregation. This, as seen before, will help us decide what we mock, when we mock and where we mock. With a rough idea of the macro design, we can start test driving the Payments module, making sure we are flexible enough to adjust our design ideas as we gain more insights through code.

For people used to Outside-In TDD and Design, mocking is a design tool, not a testing tool. Once we understand that, mocks become an excellent tool to drive the macro design of our applications.

Test-Driven Development becomes much easier when we are able to draw the boundaries of our modules. Growing complex systems one test at a time is not easy. Quickly analysing the business and doing some high-level design just before implementing a feature can save us a lot of time. Once we have an rough high-level design plan, our TDD effort becomes more focused and efficient, almost mechanical — and that is a good thing.

But what should we do when the boundaries are not clear? Sometimes we simply cannot see what the solution looks like and we need to explore. In cases like that, forget about creating a high-level design and flip straight to Classicist TDD and work in baby steps until a solution emerges. If you really need, forget TDD altogether, create a new branch, and start typing and see what happens.

For me, it is all about confidence. If I can clearly visualise the design of my modules and the type of association, I'll test-drive towards that design and will use mocks to design the interaction between different modules. If I cannot see the solution or I'm not so confident with the solution I have in my head, I'll flip to exploration mode, work in small increments, creating a small mess, and then use refactoring to decide how to organise my code better. Although it may sound a great idea to always work in small increments and refactor, I find it extremely slow and inefficient, hence the reason I mix different TDD styles.

For a great comparison between the Classicist TDD (Chicago Style) and Outside-In TDD (London Style), have a look at the Clean Coders series that Uncle Bob and I recorded. There are 14 hours of video where we pair-program, discuss, and compare the approaches.

For more about Outside-In Design, have a look at my Interaction Driven Design (IDD) talk.

For a full demonstration of Outside-In TDD, have a look at my three part screen cast: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

For a summary of the differences between Outside-In TDD and Classicist, have a look at this blog post.

Software es nuestra pasión.

Somos Software Craftspeople. Construimos software bien elaborado para nuestros clientes, ayudamos a los/as desarrolladores/as a mejorar en su oficio a través de la formación, la orientación y la tutoría. Ayudamos a las empresas a mejorar en la distribución de software.