- Por André Guelfi Torres

- ·

- Publicado 16 Apr 2019

The official documentation for Jenkins Shared Libraries is pretty good, but not perfect.

This article expands on how to use Jenkins Shared Libraries with private git repositories, semantically version, and unit test your libraries and provides working examples which you can run yourself.

Jenkins Shared Library is a handy tool when dealing with multiple similar pipelines. If you are looking for a way to reduce code duplication in your Jenkins pipelines, then this article may be the right place to start.

This article assumes the reader is somehow familiar with Jenkinsfiles or at least with the concept of a Pipeline as Code. Here is a link to my basic introduction into Jenkinsfiles if you are new to it.

Your company may be going through the Agile/DevOps transformation, and suddenly there is this push to use Continuous Integration (CI) and maybe even Continous Delivery/Deployment (CD) for every project. Or maybe it is just the teams themselves who want to start using a CI and are looking for a guide to this fancy DevOps stuff. Whatever your case may be, there are usually three common questions when starting building and deploying applications:

In my opinion, only the first question is usually taken into consideration at the beginning of the CI journey, and the last two materialise only after the newly automated pipelines grow and require a dedicated person to mainta… Wait a minute this is not what DevOps was supposed t… Well, never mind, let's keep going.

What CI should we use?

The answer to this question is u̶n̶f̶o̶r̶t̶u̶n̶a̶t̶e̶l̶y̶ usually "Jenkins" as it is still the most popular and feature-rich CI on the market. Oh, and it's free, which makes it by default one of the best candidates in the eyes of your management.

Our pipelines are pretty similar. How can we avoid duplication?

This question is more interesting as there are a couple of options for Jenkins. One option is to use Jenkins Job DSL plugin (JDSL) to automate the initial creation and content of your jobs completely, but using JDSL usually implies that there is one Jenkins instance for multiple teams or a central one for the whole company (this works well when all projects follow the same convention). Also, the initial cost of creating a quality seed JDSL job can be time-consuming and it pays itself of the more jobs you create with it. So what if you don't want to invest in JDSL heavily? My answer to that is to try Jenkins Shared Library (JSL). Although it is possible to combine JDSL with JSL, in this article, I'm going to focus on JSL alone.

Is it reasonable to unit test the pipelines?

Let me ask you this: How do you want to test new pipeline features? Is it ok for you if after every little change you have to push the changes to Jenkins and wait for the build to see them in action? If not then you will have to either be able to run your pipelines locally without the CI server present or unit tests part of them.

In an ideal world, all pipelines would be dead simple, idempotent, written in a declarative way (e.g. using ansible playbooks) with no logic in them and you should be able to test run them locally without the CI server present.

However, if in Jenkins pipelines, you are going to use groovy, then it isn't uncommon to have a logic-creep infesting the stages of your pipelines. In this case, if you use JSL then you can unit test the code as if you would test any other groovy code.

Currently, it is tough to test any infrastructure related code as a whole as it requires an expensive mix of mocking, isolation, and idempotency. However, if you have a chance to easily unit test part of a pipeline, then do so. From my experience when you have to unit tests a big chunk of the pipeline it means that that code should be extracted as a (Jenkins) plugin because a plugin for it does not exist yet.

Some automation tools have "dry run" mode, but with more complex scenarios, it falls short. Unfortunately, testability is still not a primary concern with most infrastructure tools.

The more similar the pipelines are in your organisation the better the outcome you can expect from using JSL.

There are some unavoidable hindrances but think of it this way: the alternatives usually boil down to some sort of code duplication or nasty practices like keeping all of your company source code in one humongous code repository (monorepo) using a VCS not designed for it.

Here it is:

This may feel like it slows you down but think of the alternatives. Code duplication is a maintenance nightmare. If you think monorepo is the answer then unless you are using piper I would shy away from it.

In short, JSL comes with the benefits and costs similar to creating and maintaining an open source library. On top of that, it suffers from e2e testability which for me is the biggest drawback. I hope that in the future we will be able to get our hands on a CI which comes with testable pipelines as a first-class citizen.

JSL is usually a semantically versioned gradle groovy project kept in a git repository which is git cloned by Jenkins and put on a classpath when a pipeline job using a Jenkinsfile request for it. (yikes!)

If you understood the previous paragraph then you probably already have a good picture in your mind how it all works together. If not then don't worry, we will go step by step and explain along the way.

To figure out what Jenkins is actually doing behind the scenes we are going to run the most basic pipeline job which uses JSL.

To demonstrate what Jenkins is doing when using a JSL I will need a Jenkins instance. I'm going to run one on my local machine and for that I'm going to use my GitHub project with a dockerized Jenkins, a couple of exemplary Jenkinsfiles and another dockerized service which will load my Jenkinsfiles from a folder and tell Jenkins to create jobs out of them.

This setup is only for demonstration purposes and is not suitable for production usage.

If you want to follow this post and run the examples then you need to have docker and docker-compose installed.

git clone https://github.com/hoto/jenkinsfile-examples.git -b blog-jenkins-shared-libraries

cd jenkinsfile-examples

docker-compose pull

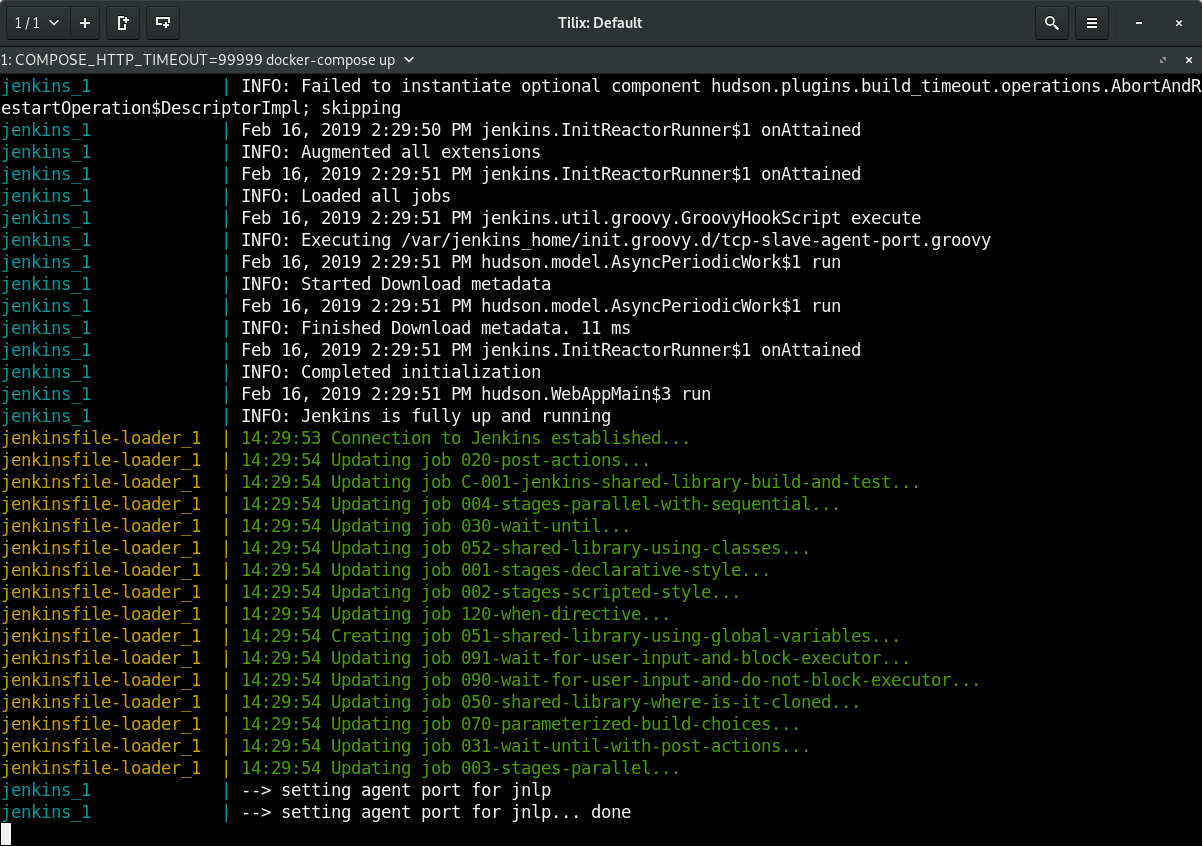

docker-compose up

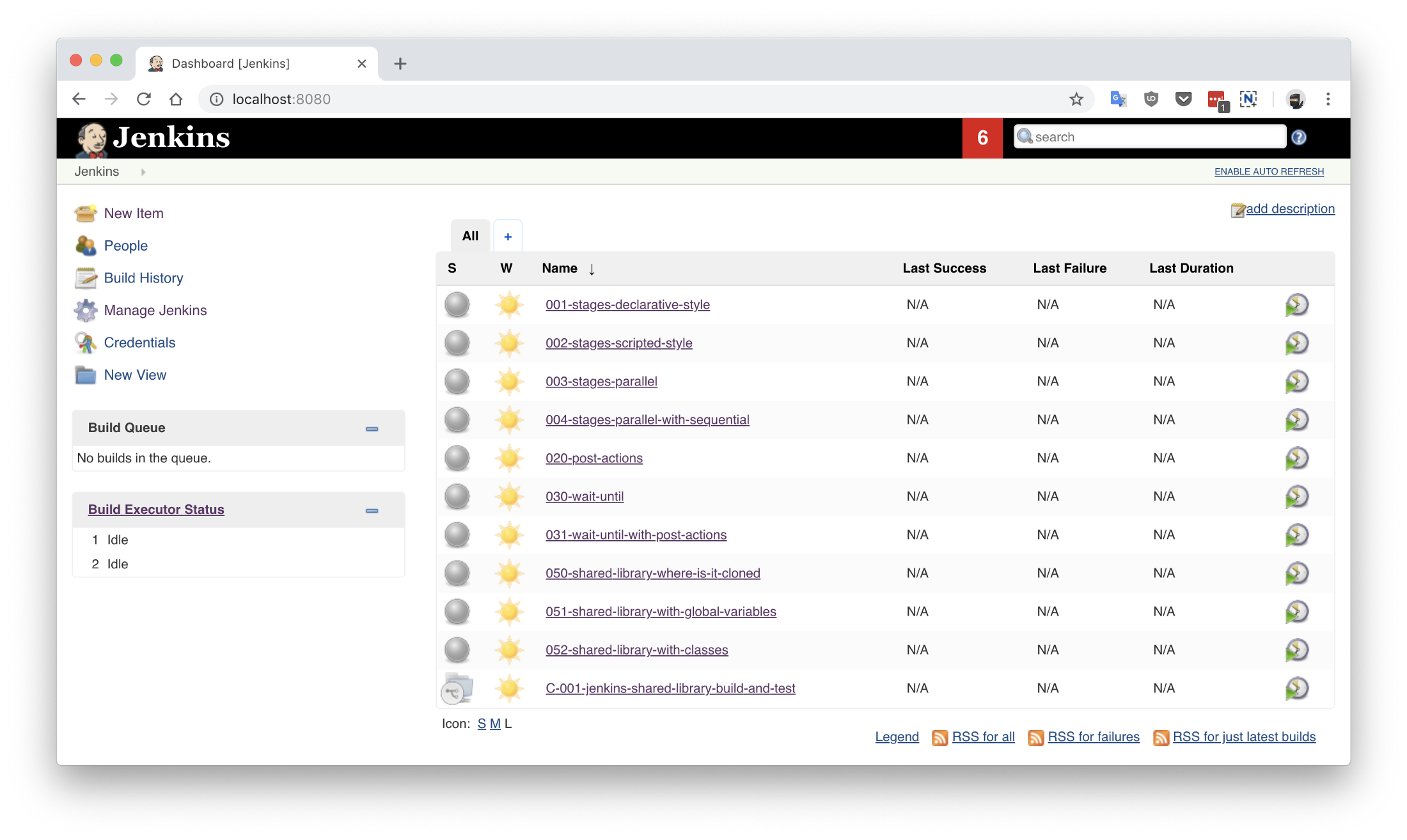

Jenkins should be available in your web browser on localhost:8080

There are a couple of jobs there already. Their config is based on the Jenkinsfiles <job_name>.groovy files located in the jenkinsfiles directory inside the repository. Editing, creating or deleting any of those Jenkinsfiles will cause the change to be reflected immediately in Jenkins (sometimes refreshing the page is required).

Jenkins is setup with authentication disabled and a couple of pre-installed plugins so it can be used immediately after it runs.

Structure of jenkinsfile-examples project:

$ pwd

~/projects/jenkinsfile-examples

$ tree

.

├── Dockerfile

├── docker-compose.yml

├── configs

│ └── C-001-jenkins-shared-library-build-and-test.xml

├── jenkinsfiles

│ ├── 001-stages-declarative-style.groovy

│ ├── 002-stages-scripted-style.groovy

│ ├── 003-stages-parallel.groovy

│ ├── 004-stages-parallel-with-sequential.groovy

│ ├── 020-post-actions.groovy

│ ├── 030-wait-until.groovy

│ ├── 031-wait-until-with-post-actions.groovy

│ ├── 050-shared-library-where-is-it-cloned.groovy

│ ├── 051-shared-library-using-global-variables.groovy

│ ├── 052-shared-library-using-classes.groovy

│ ├── 070-parameterized-build-choices.groovy

│ ├── 090-wait-for-user-input-not-blocking-executor.groovy

│ └── 091-wait-for-user-input-blocking-executor.groovy

└── source

└── jenkins

└── usr

└── share

└── jenkins

├── plugins.txt

└── ref

├── config.xml

└── scriptApproval.xml

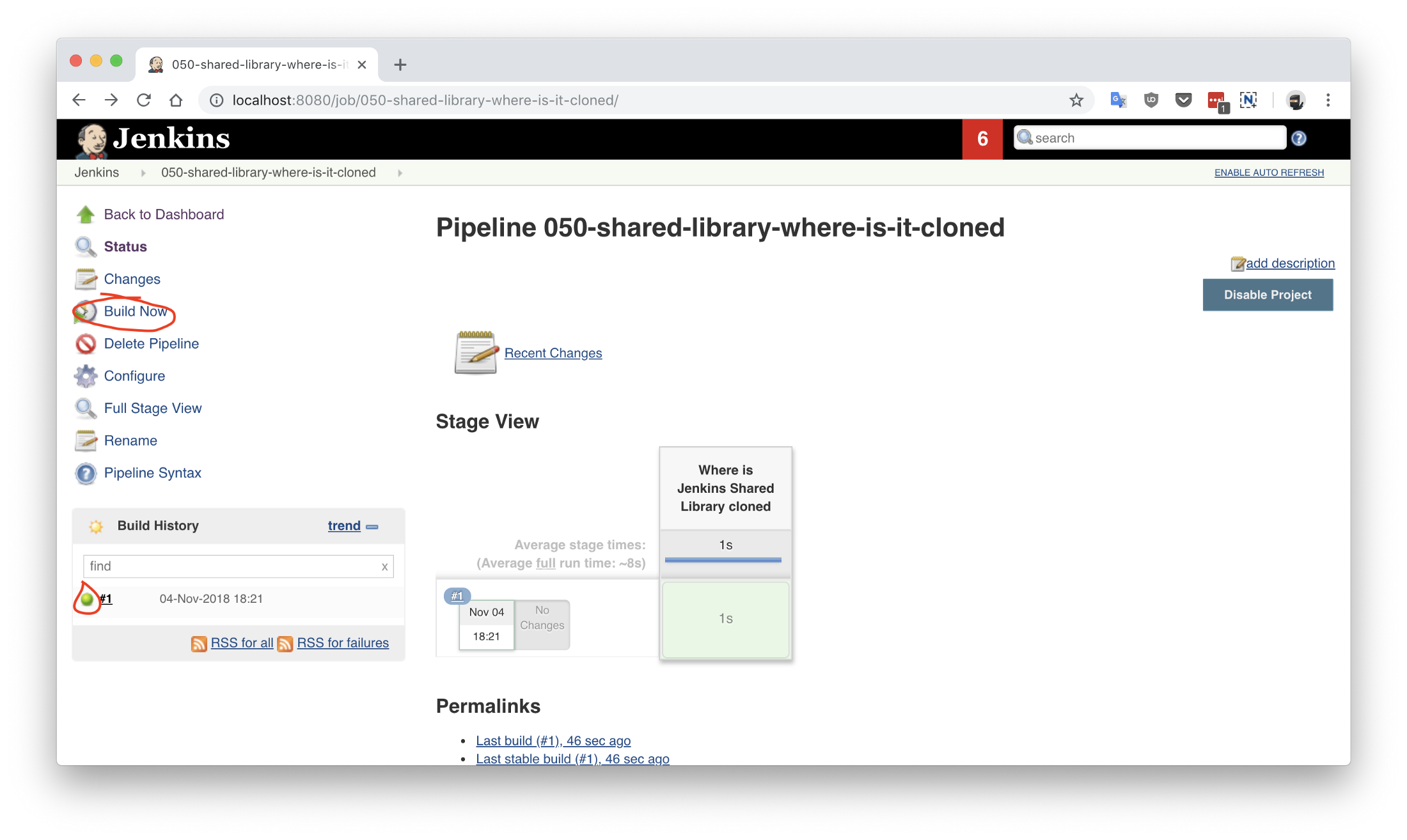

Let's run a job called 050-shared-library-where-is-it-cloned which uses a following Jenkinsfile 050-shared-library-where-is-it-cloned.groovy (as you can see Jenkinsfiles can be named whatever but in your projects keep the convention of calling it Jenkinsfile):

library(

identifier: 'jenkins-shared-library@1.0.4',

retriever: modernSCM(

[

$class: 'GitSCMSource',

remote: 'https://github.com/hoto/jenkins-shared-library.git'

]

)

)

pipeline {

agent any

stages {

stage('Where is Jenkins Shared Library cloned') {

steps {

script {

sh 'ls -la ../050-shared-library-where-is-it-cloned@libs/jenkins-shared-library'

}

}

}

}

}

What should be interesting to us about this job is that it:

library located at https://github.com/hoto/jenkins-shared-library referencing git tag 1.0.4Let's run it and go through the build logs.

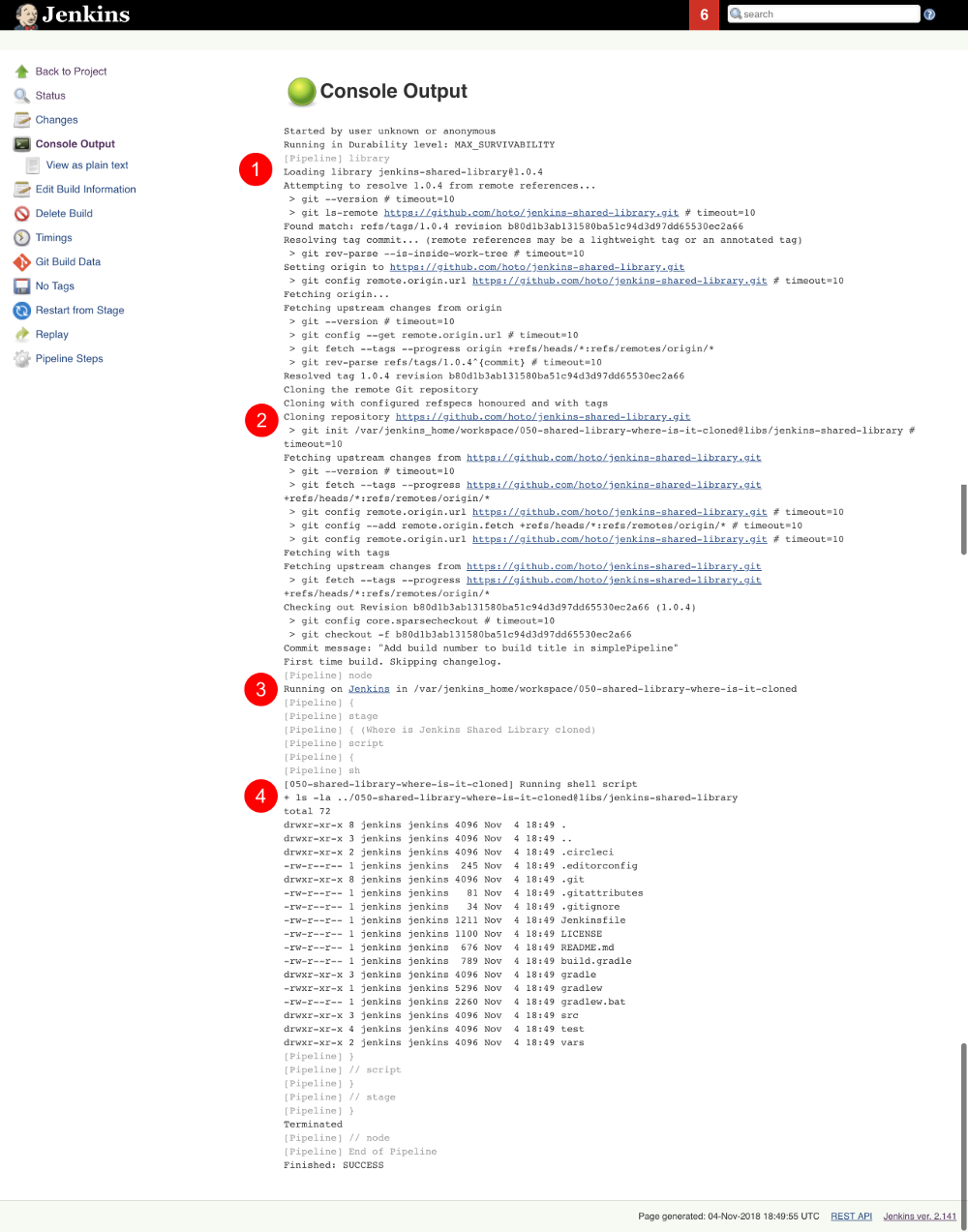

Breaking down the logs:

Jenkins tries to load the shared library:

Loading library jenkins-shared-library@1.0.4

Attempting to resolve 1.0.4 from remote references...

It can't find it so it clones the referenced git repository https://github.com/hoto/jenkins-shared-library.git and checks out a commit tagged 1.0.4:

git init /var/jenkins_home/workspace/050-shared-library-where-is-it-cloned@libs/jenkins-shared-library

...

git config remote.origin.url https://github.com/hoto/jenkins-shared-library.git

...

Checking out Revision b80d1b3ab131580ba51c94d3d97dd65530ec2a66 (1.0.4)

Library repository has been cloned outside of the job workspace into ../050-shared-library-where-is-it-cloned@libs/jenkins-shared-library directory. We can verify that from the command executed inside the stage:

ls -la ../050-shared-library-where-is-it-cloned@libs/jenkins-shared-library

total 72

drwxr-xr-x 8 jenkins jenkins 4096 Nov 4 18:49 .

drwxr-xr-x 3 jenkins jenkins 4096 Nov 4 18:49 ..

drwxr-xr-x 2 jenkins jenkins 4096 Nov 4 18:49 .circleci

-rw-r--r-- 1 jenkins jenkins 245 Nov 4 18:49 .editorconfig

drwxr-xr-x 8 jenkins jenkins 4096 Nov 4 18:49 .git

-rw-r--r-- 1 jenkins jenkins 81 Nov 4 18:49 .gitattributes

-rw-r--r-- 1 jenkins jenkins 34 Nov 4 18:49 .gitignore

-rw-r--r-- 1 jenkins jenkins 1211 Nov 4 18:49 Jenkinsfile

-rw-r--r-- 1 jenkins jenkins 1100 Nov 4 18:49 LICENSE

-rw-r--r-- 1 jenkins jenkins 676 Nov 4 18:49 README.md

-rw-r--r-- 1 jenkins jenkins 789 Nov 4 18:49 build.gradle

drwxr-xr-x 3 jenkins jenkins 4096 Nov 4 18:49 gradle

-rwxr-xr-x 1 jenkins jenkins 5296 Nov 4 18:49 gradlew

-rw-r--r-- 1 jenkins jenkins 2260 Nov 4 18:49 gradlew.bat

drwxr-xr-x 3 jenkins jenkins 4096 Nov 4 18:49 src

drwxr-xr-x 4 jenkins jenkins 4096 Nov 4 18:49 test

drwxr-xr-x 2 jenkins jenkins 4096 Nov 4 18:49 vars

Purpose of 050-shared-library-where-is-it-cloned job is only to show how Jenkins downloads the shared library into its workspace. Now let's run something more useful.

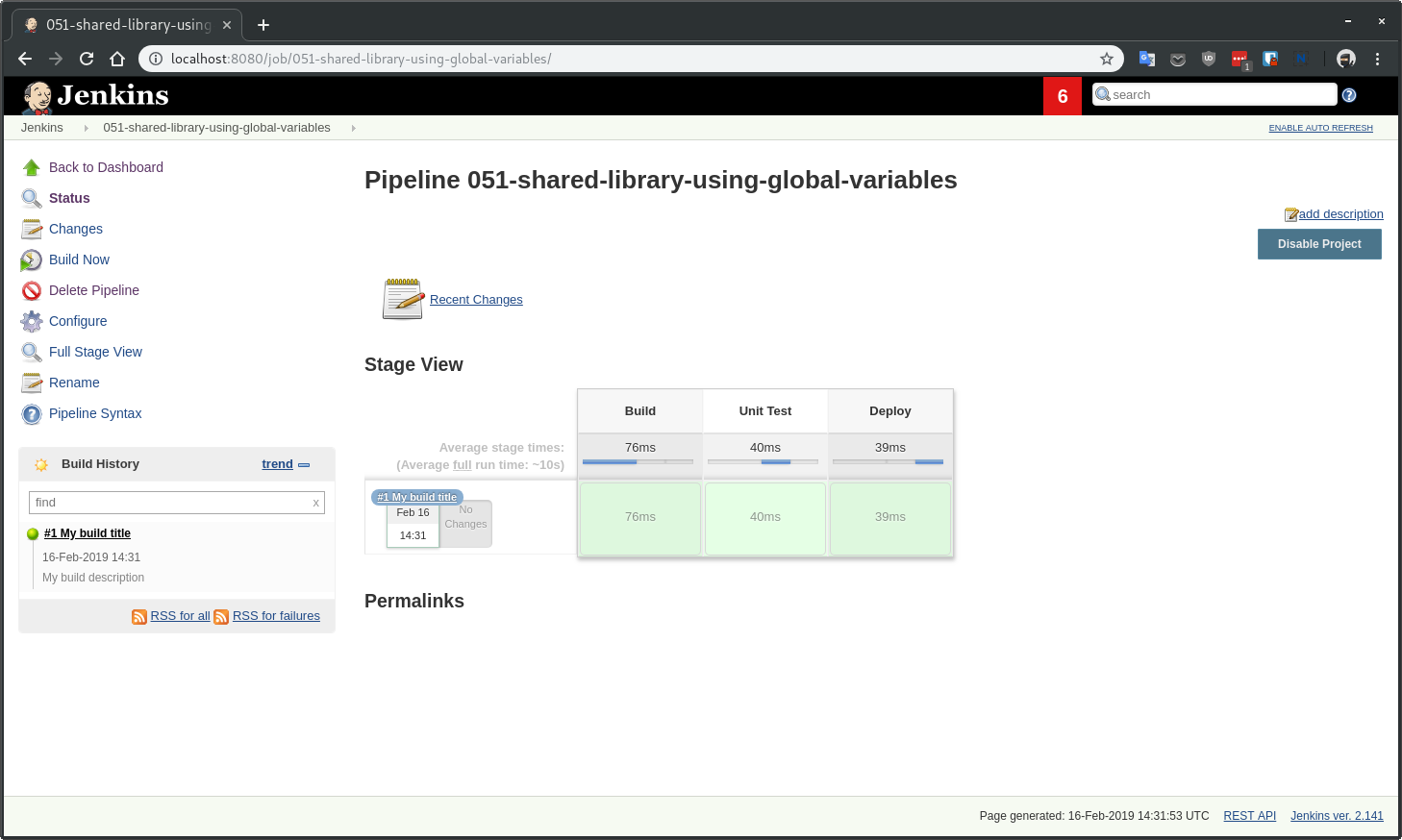

Job 051-shared-library-using-global-variables is utilising Jenkins scripted pipeline model with fluent interface design pattern making it possible to write elegant, generic, and reusable pipelines. If you have a lot of similar projects, you could make a template repository with generic Jenkinsfile using this approach and easily script the creation of new projects and their pipelines.

This model is my preferred one as it offers the most power, reusability, and versatility while making the pipelines easy to read at the same time. I recommend you try it first.

There are two strategies to write pipelines like this:

Abstract everything, including the commands themselves. This only works when all projects follow the same convention, which is known to everybody in the company. A drawback of doing so will make it hard to tell what commands are used to build a project with just looking at the Jenkinsfile.

Abstract everything but the commands. This is useful when your company does not have a single convention to build similar projects. If you have lot's of legacy projects, then using this strategy will probably save you some headaches.

This example is using strategy #2:

jsl = library(

identifier: 'jenkins-shared-library@1.0.4',

retriever: modernSCM(

[

$class: 'GitSCMSource',

remote: 'https://github.com/hoto/jenkins-shared-library.git'

]

)

)

simplePipeline([jsl: jsl])

.build(

command: 'My build command'

)

.unitTest(

command: 'My unit test command'

)

.deploy(

command: 'My deploy command'

)

Also, you could split the build phase from the deployment phase when the pipeline grows to make things easier to maintain.

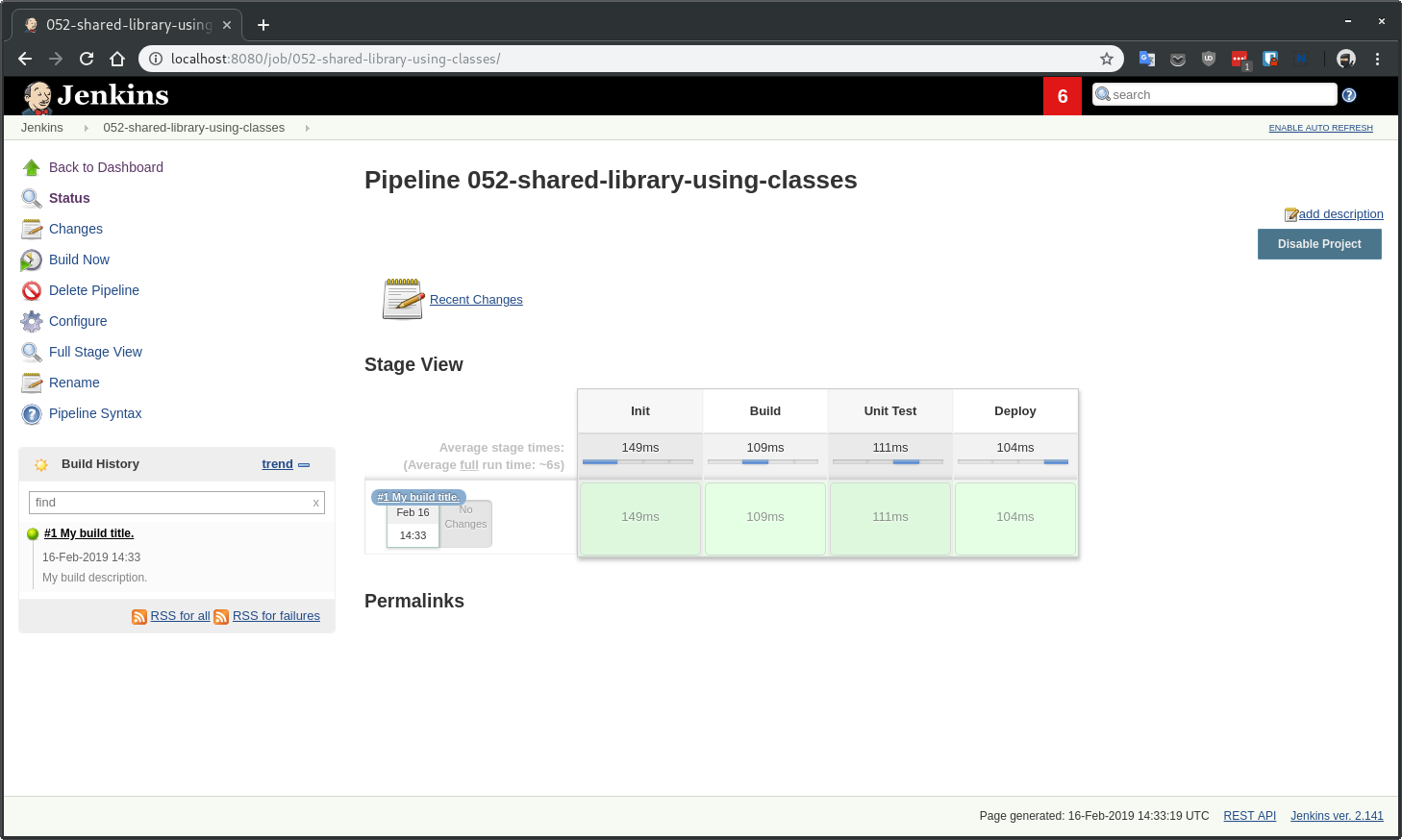

Job 052-shared-library-using-classes is using the new Jenkins declarative pipeline model. I find the declarative model useful when quickly creating a pipeline for a single project. It falls short very quickly when you try to abstract it away for multiple projects. I would stay away from it and write a custom pipeline using the scripted model.

You could still mix declarative model with the scripted one but I would not recommend it, anyway here is an example:

jsl = library(

identifier: 'jenkins-shared-library@1.0.4',

retriever: modernSCM(

[

$class: 'GitSCMSource',

remote: 'https://github.com/hoto/jenkins-shared-library.git'

]

)

)

def build = jsl.com.mycompany.jenkins.Build.new(this)

pipeline {

agent any

stages {

stage('Init') {

steps {

script {

build.setBuildDescription(

title: "#${env.BUILD_NUMBER} My build title.",

description: 'My build description.'

)

}

}

}

stage('Build') {

steps {

script {

echo 'Building...'

}

}

}

stage('Unit Test') {

steps {

script {

echo 'Unit Testing...'

}

}

}

stage('Deploy') {

steps {

script {

echo 'Deploying...'

}

}

}

}

}

In the examples I'm using in this post the referenced JSL is cloned from my public repository on GitHub. By reference I mean this part:

jsl = library(

identifier: 'jenkins-shared-library@1.0.4',

retriever: modernSCM(

[

$class: 'GitSCMSource',

remote: 'https://github.com/hoto/jenkins-shared-library.git'

]

)

)

Now, what if you want the JSL repository to be private? That is very easy to do.

To clone a private JSL repository Jenkins needs to be able to authenticate with the hosting provider. You can achieve this in many different ways:

By using basic authentication (user and password) added to your Jenkins credentials and then referencing the credentialsId:

jsl = library(

identifier: 'jenkins-shared-library@1.0.4',

retriever: modernSCM(

[

$class: 'GitSCMSource',

remote: 'https://github.com/hoto/jenkins-shared-library.git',

credentialsId: 'github-cicd-user'

]

)

)

By using an ssh key added to your Jenkins credentials and then referencing the credentialsId:

jsl = library(

identifier: 'jenkins-shared-library@1.0.4',

retriever: modernSCM(

[

$class: 'GitSCMSource',

remote: 'git@github.com:hoto/jenkins-shared-library.git',

credentialsId: 'github-cicd-ssh-rw'

]

)

)

By adding an ssh key to your Jenkins instance and reference JSL with private ssh URL e.g. git@github.com:hoto/jenkins-shared-library.git This can actually be tricky to configure correctly so depending on your Jenkins setup try other approaches first. Also, this approach is not my favourite as it is "magical" because it hides the details of how Jenkins authenticates and which ssh key is used.

Also, JSL repository obviously does not have to be hosted on GitHub (it does not even need to be a git repository), it could be hosted from a private GitLab or Bitbucket etc.

We've looked how to use a JSL, but how do we structure the JSL repository? Let's deconstruct the shared library repository used in this article.

The source code is located at https://github.com/hoto/jenkins-shared-library/tree/1.0.4 .

The full structure of the repository, as of tag 1.0.4:

$ pwd

~/projects/jenkins-shared-library

$ tree -a

.

├── .circleci

│ └── config.yml

├── Jenkinsfile

├── build.gradle

├── gradle

│ └── wrapper

│ ├── gradle-wrapper.jar

│ └── gradle-wrapper.properties

├── gradlew

├── gradlew.bat

├── src

│ └── com

│ └── mycompany

│ └── jenkins

│ ├── Build.groovy

│ └── Git.groovy

├── test

│ ├── com

│ │ └── mycompany

│ │ └── jenkins

│ │ ├── BuildShould.groovy

│ │ └── GitShould.groovy

│ └── mocks

│ └── WorkflowScriptStub.groovy

└── vars

└── simplePipeline.groovy

Let's break this project down starting from the top.

├── .circleci

│ └── config.yml

├── Jenkinsfile

├── build.gradle

├── gradle

│ └── wrapper

│ ├── gradle-wrapper.jar

│ └── gradle-wrapper.properties

├── gradlew

├── gradlew.bat

This repository is a standard gradle groovy project, there is nothing special about it. It's using a gradle wrapper gradlew checked into the source control. This is a standard procedure, doing so makes it possible to ensure the CI is using the same gradle version as developers. Another advantage is that by using gradlew (unix) or gradlew.bat (windows) script you don't need gradle installed, it will download gradle binary into the repository.

I've included a Jenkinsfile in the project but it is unused as I don't want to pay for a machine running Jenkins. I still wanted automatic testing of my shared library project on every push to the repository so I've added a .circleci/config.yml file and hooked up my GitHub repository to a free circleci online service.

If this were a real case scenario, I would use a Jenkins instance and create a multi-branch pipeline job referencing the shared library repository. However, there is no jenkins-as-a-service, so I'm using circle ci in this example.

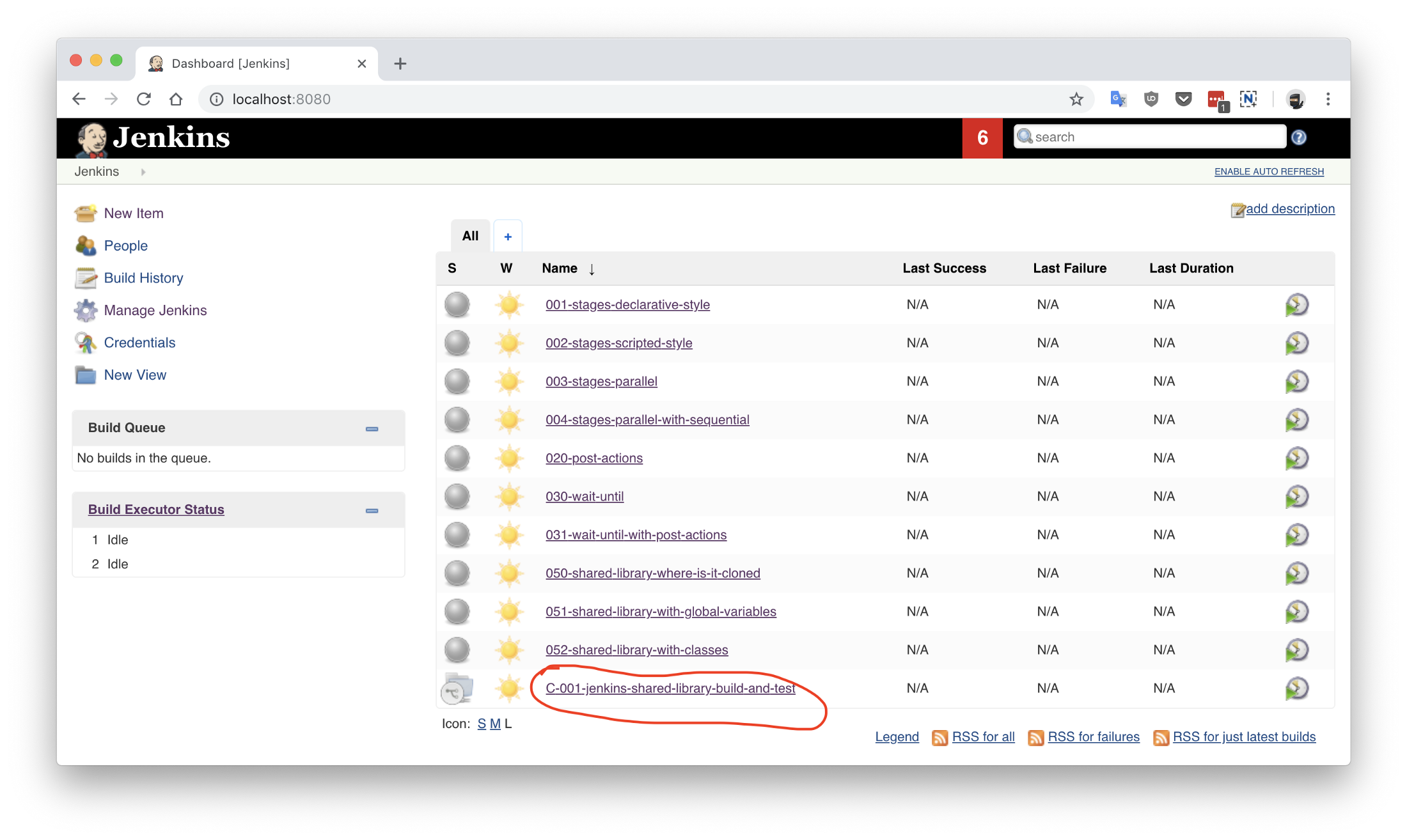

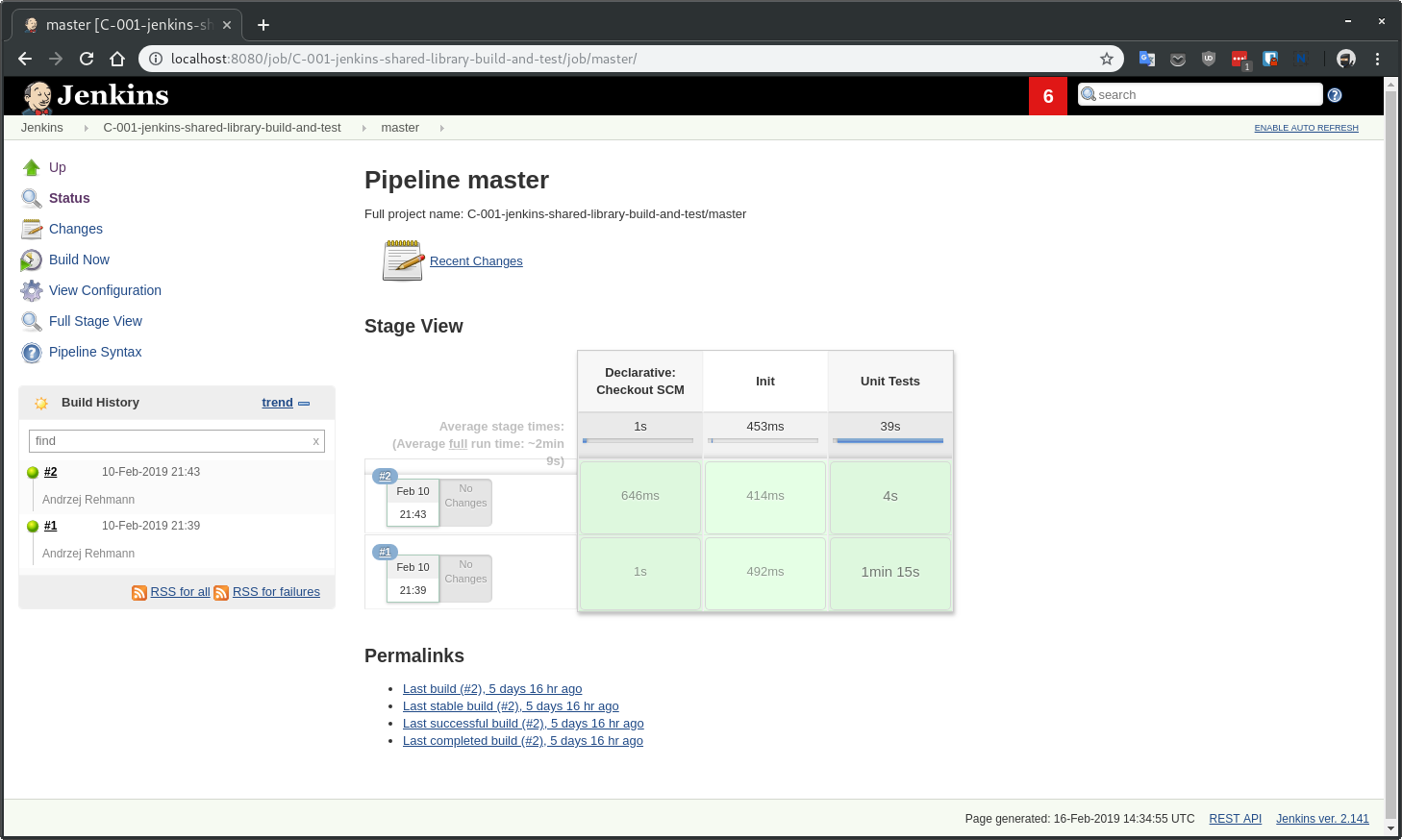

To show you how to use Jenkins instance to test your JSL repository a pre-made job config is included in jenkinsfile-examples project called C-001-jenkins-shared-library-build-and-test:

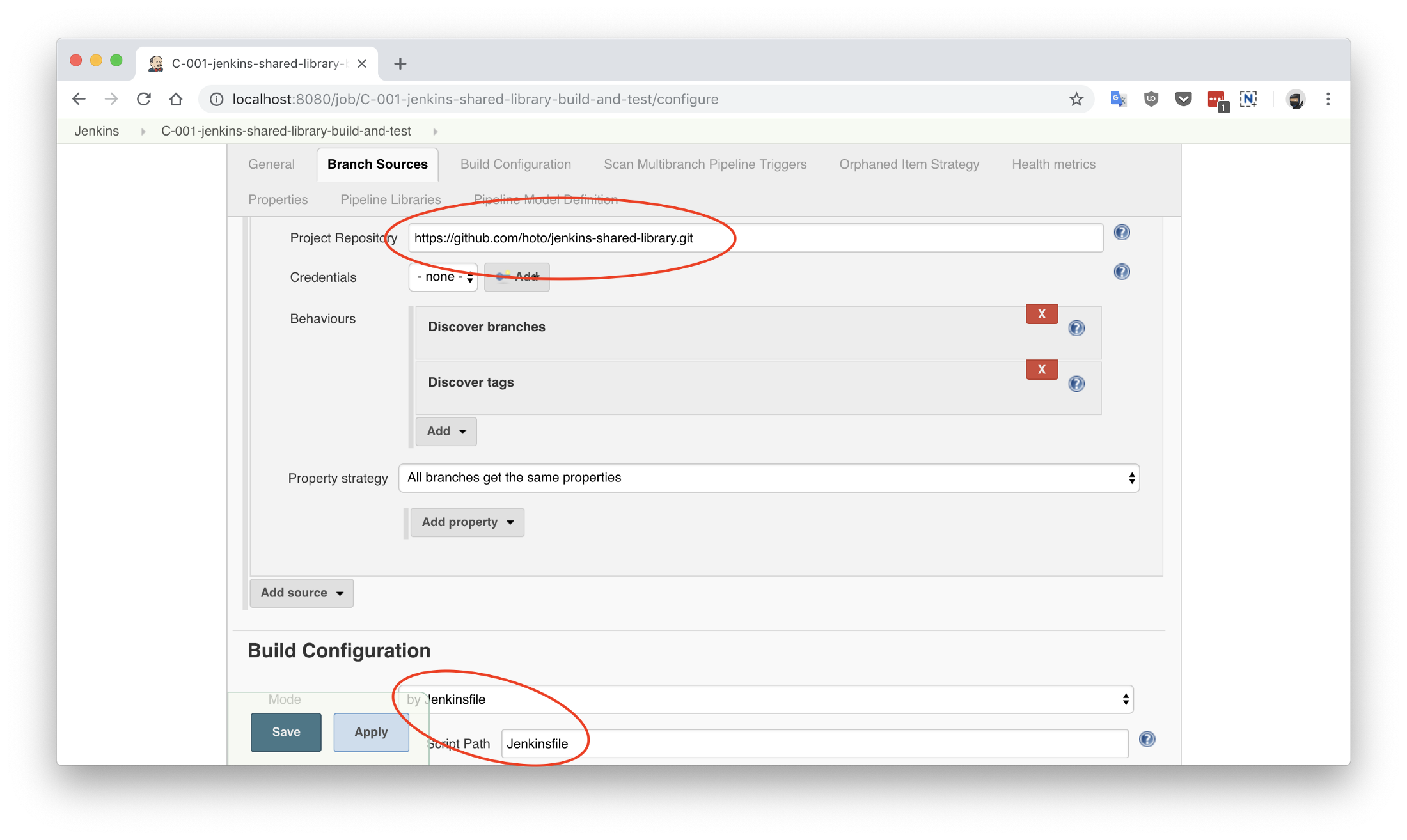

Because my JSL project is a standard gradle git repository there are only two things you need to specify in a multi-branch pipeline job: project repository location (GitHub) and location of Jenkinsfile (root). Open C-001-jenkins-shared-library-build-and-test job settings to verify that:

Let's have a look at the jenkinsfile-shared-library Jenkinsfile and then finally run the job.

jsl = library(

identifier: "jenkins-shared-library@${env.BRANCH_NAME}",

retriever: modernSCM(

[

$class: 'GitSCMSource',

remote: 'https://github.com/hoto/jenkins-shared-library.git'

]

)

)

build = jsl.com.mycompany.jenkins.Build.new(this)

git = jsl.com.mycompany.jenkins.Git.new(this)

pipeline {

agent {

docker {

image 'docker.io/gradle:4.5.1-jdk8'

args '-v /root/.gradle:/home/gradle/.gradle'

}

}

options {

timeout(time: 5, unit: 'MINUTES')

}

stages {

stage('Init') {

steps {

script {

COMMIT_MESSAGE = git.commitMessage()

COMMIT_AUTHOR = git.commitAuthor()

build.setBuildDescription(

message: COMMIT_MESSAGE,

description: COMMIT_AUTHOR

)

}

}

}

stage('Unit Tests') {

steps {

script {

sh './gradlew test'

}

}

}

}

}

There are two things worth noticing about this particular pipeline:

It's using docker as an agent for every stage making it very easy to run as only docker is needed on a Jenkins executor. No tools and compilers have to be installed on Jenkins, everything comes from a docker container.

It uses a neat trick of referencing itself when building and testing itself.

If you haven't noticed the pipeline is using a shared library which points to itself:

jsl = library(

identifier: "jenkins-shared-library@${env.BRANCH_NAME}",

retriever: modernSCM(

[

$class: 'GitSCMSource',

remote: 'https://github.com/hoto/jenkins-shared-library.git'

]

)

)

On top of it, the identifier points to a library version using an environment variable ${env.BRANCH_NAME}. When you combine this with a multi-branch pipeline job and gated pull requests, you are technically able to add new pipeline features and unit test them at the same time before you merge them into the master branch. Think of it; the possibilities are endless… But honestly, I don't think cramming all of your pipelines features into a single Jenkinsfile is practical. More likely you would end up using a couple of components, and that's it.

First, build of Unit Tests stage took 1min 15s yet after retrying the same build it took only 4s as all of the dependencies has been already cached on the host. This is done by passing some extra arguments to docker to mount the gradle cache from the host args '-v /root/.gradle:/home/gradle/.gradle' Otherwise each new stage would have to download all of the dependencies each time as each stage is a new docker container.

In groovy you can use either classes or scripts. IMHO most of the logic should be put into unit testable classes and then referenced from groovy scripts (Jenkinsfile itself is a groovy script).

├── src

│ └── com

│ └── mycompany

│ └── jenkins

│ ├── Build.groovy

│ └── Git.groovy

├── test

│ ├── com

│ │ └── mycompany

│ │ └── jenkins

│ │ ├── BuildShould.groovy

│ │ └── GitShould.groovy

│ └── mocks

│ └── WorkflowScriptStub.groovy

The src directory is similar to a standard Java source directory structure. This directory is added to the classpath when executing a pipeline.

In tests, I'm using spock test framework which is a nice benefit of using groovy for unit tests.

The vars directory hosts scripts that define global variables accessible from the pipeline. The base name of each <name>.groovy file is a camelCased identifier.

└── vars

└── simplePipeline.groovy

Official documentation is using "global variables" for something that to me looks like functions. I'm not a Jenkins or groovy expert so I'm gonna use the same nomenclature as to not confuse people.

The only file in my vars folder: simplePipeline.groovy is a custom step directive. It is a step because it contains a function with a special declaration call(Map args) .

def call(Map args) {

someCodeHere()

}

That call function will be triggered when you call simplePipeline(args) from anywhere in the pipeline.

I'm not going to go into many details here but take note that there are a couple of other different "global variables" you can use.

To give you an idea of how a pipeline using JSL could look like here is one example from a project I have been working on. There is still a lot of room for improvement though.

jsl = library(

identifier: 'jenkins-shared-library@17.0.0',

retriever: modernSCM(

[

$class : 'GitSCMSource',

remote : 'ssh://git@bitbucket.mycompany.com/ftl/myservice.git',

credentialsId: 'bitbucket-cicd-ssh-rw'

]

)

)

def buildData = environment.gatherBuildData(

jsl: jsl,

projectName: 'myservice',

projectRepositoryUrl: 'https://bitbucket.mycompany.com/projects/ftl/repos/myservice',

teamName: 'FTL',

servicesNames: ['myservice'],

servicesUrls: [

myservice: [

test: 'http://myservice.dev.mycompany.com',

pre : 'http://myservice.pre.mycompany.com',

pro : 'http://myservice.pro.mycompany.com'

]

],

mainBranch: 'master'

)

bitbucket(buildData).jobInProgress()

def slack = newSlack(

jsl: jsl,

buildData: buildData,

officialChannel: '#ftl-builds',

testChannel: '#ftl-builds-test',

whenBranch: 'master'

)

dockerPipeline(jsl: jsl, type: 'maven', buildData: buildData)

.withSlack(slack)

.setBuildDescription()

.build("""

./mvnw versions:set -D newVersion='${buildData.version}' -D generateBackupPoms=false

./mvnw clean package -D skipTests

""")

.unitTests('./mvnw test')

.integrationTestsWithPostgres('./mvnw verify -D skipTests')

.pactTests("""

./mvnw test \

-D skipTests=true \

-D skipPacts=false \

-D pact.provider.version='${buildData.version}' \

-D pact.verifier.publishResults=

""")

.gitTag(

tag: buildData.version,

whenBranch: 'master'

)

deployment(jsl: jsl, buildData: buildData)

.withSlack(slack)

.deployTest(

serviceName: 'myservice',

artifactDir: './myservice-parent/myservice-webapp/target/',

artifactName: "myservice-${buildData.version}.zip",

whenBranch: 'master'

)

.deployPre(

serviceName: 'myservice',

artifactDir: './myservice-parent/myservice-webapp/target/',

artifactName: "myservice-${buildData.version}.zip",

whenBranch: 'master'

)

.gatling(

environment: 'PRE',

type: 'maven',

command: """

./mvnw gatling:execute \

-pl myservice-parent/myservice-stress \

-D myservice.stress.environment=pre

""",

whenBranch: 'master'

)

.promoteArtifactFromPreToPro(

serviceName: 'myservice',

artifactName: "myservice-${buildData.version}.zip",

whenBranch: 'master'

)

.createJiraTicketRequestingDeploymentToPro(

whenBranch: 'master'

)

bitbucket(buildData).jobSucceeded()

To wrap this up. Jenkins Shared Library takes time and effort to learn and set up correctly. Try to make your pipelines as declarative as possible and unit test only the parts with logic in them.

Before you write any custom code for your pipeline in groovy, check if there is a plugin for it first. Jenkins has thousands of them, and that's the main reason it is so popular.

If you are blessed and you are dealing with only containers in production using proper tools you should have it easier to make your pipelines simple.

On the other hand, if you are dealing with a ton of legacy apps, no containers and obscure bash scripts then instead of rewriting pipelines to groovy maybe have a look at Ansible? However, that's a topic for another time.

Software es nuestra pasión.

Somos Software Craftspeople. Construimos software bien elaborado para nuestros clientes, ayudamos a los/as desarrolladores/as a mejorar en su oficio a través de la formación, la orientación y la tutoría. Ayudamos a las empresas a mejorar en la distribución de software.