- Por Matt Belcher

- ·

- Publicado 09 Jun 2020

SOLID (single responsibility, open-closed, Liskov substitution, interface segregation and dependency inversion) is a set of principles popularised by ‘Uncle’ Bob Martin that aim to guide developers in implementing good software design. The principles define how Object Oriented classes should relate to each other in order to create a codebase that is flexible and able to accommodate ongoing change.

The first of these, the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) states that -

"Every module or class should have one, and only one reason to change."

Source: Wikipedia

There are scores of tutorials out there providing very good code examples of SRP implementation and there is little value in presenting a similar tutorial here. I have provided links to some of these tutorials at the end of this article.

What I would like to do is give some food for thought about the merits of applying SRP in day to day practice. My hunch, based on what I have read on the subject is that SRP could be prone to misinterpretation. As explained later in this article, the definition of SRP is not entirely obvious. Often the tutorials availbale view SRP in a narrow context, without considering the wider application. When applied incorrectly, I think SRP can do your code more harm than good. In the interests of taking a balanced view we will explore what impacts SRP can have on your code, both positive and negative, and I will share some tips on ways to successfully implement this important principle.

Being the first of the SOLID principles, SRP is perhaps at the fore-front of developers’ minds, particularly, as its definition is deceptively simple in contrast to the other principles. Here though, lies the first problem with SRP. Its own name makes a clear reference to responsibilities but the definition subsequently seems to bear a weak relationship to this.

So what’s going on?

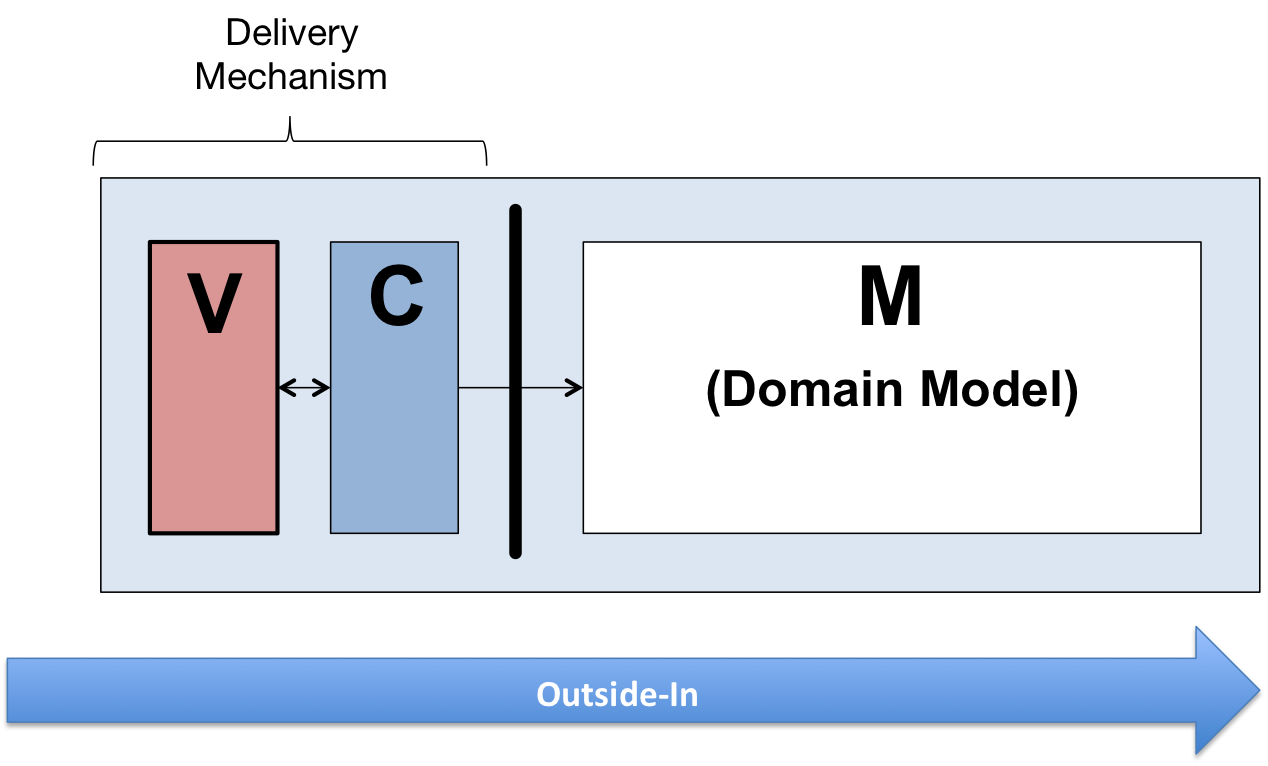

Digging a little deeper into Uncle Bob’s writings we see that SRP is really about dealing with sources of change - specifically, the actors in the organisation who end up utilising the functionality provided by the application. Quite rightly, he argues that the needs of an actor can and will change, therefore, the functionality that serves the actor will also change. Ultimately, he defines a ‘responsibility’ as a ‘family of functions that serve one particular actor’.

So what happens if you violate single responsibility? If a class assumes more than one responsibility, then there will be more than one reason for it to change. If a class has more than one responsibility, then the responsibilities become coupled. Changes to one responsibility may impair or inhibit the class’ ability to meet the others. This kind of coupling leads to fragile designs that can break in unexpected ways when changed.

Ok, so sounds logical enough.

Large monolithic classes with multiple responsibilities are bad.

So what’s the alternative?

Read the many articles online and you can see the common implementation of SRP is going from large monolithic classes to small classes containing a significantly smaller number of methods. The danger here is that as you introduce more and more classes into your design, you expose new risks. Taken to the extreme, Marco Ceconni argues in his post titled ‘I don’t love the single responsibility principle’ that a shotgun approach to SRP can result in large numbers of anemic micro-classes that do little and complicate the organisation of the code base.

At first, it may appear on the surface that introducing new abstractions, particularly if they represent some aspect of an agreed domain model, is a good thing. The business’ view of the world is represented accurately in the code, allowing developers and domain experts to share a common (ubiquitous) language. On the flip-side, Mash Badar argues in his post ‘Thinking in Abstractions’ that introducing new classes (or abstractions in general) often results in more code overall, not less. Any abstractions that are part of the business domain are particularly vulnerable to change. Once a new abstraction is embedded in the design, a change to it can still have the potential to cause unexpected changes elsewhere in the codebase.

Being able to identify sources of change, which is at the core of the SRP definition, is difficult. Sources of change can be driven by unknown factors that are out of our control. We therefore strive to make a 'best guess', ensure our code can accommodate change, and continue to reduce risk as we iterate. But even with best intentions, it’s not just the unknown that poses a risk to good software design, it’s coming to a consensus on how to manage the unknown that might be an equal or greater risk. If the process of identifying sources of change is subjective, we will design classed based on flawed assumptions which will bear little fruit in the long run.

So like many recognised ‘best practices’ in software development, there seems to be two sides to the story when it comes to SRP.

What’s a confused developer to do?

In order to organize code with minimal complexity Marco Ceconni recommends striking a balance when it comes to using SRP. Classes should be:

Small enough to lower coupling, but

Large enough to maximize cohesion.

The second point is important, and potentially one that is overlooked. The key message is not to create new abstractions unnecessarily. Particularly, for example, if it makes logical sense that two classes are merged, rather than be separate. Each class should ‘pull it’s own weight’, meaning it should be clear unanimously what role a class has within the application and the value it provides.

Timing, and in particular, thinking about where your application is in relation to the project lifecycle is certainly worthy of your consideration. Exercising single responsibility too early on in the project lifecycle will likely cause problems down the road. As mentioned earlier, abstractions based on the business domain are particularly vulnerable to change throughout the lifecycle, perhaps more so at the beginning.

On a recent pet project of mine, I did make the mistake of optimising prematurely. I had unknowingly, applied SRP too liberally at the start of the project. I stood there, gazing at the code base, feeling rather proud of myself as I looked upon my army of tiny, encapsulated classes. Problem was that I had got my data model wrong. I had to make some significant changes to this which ended up causing massive ripple effects throughout my codebase. Needless to say I spent a fair amount of time fixing my code as a result, and this mistake ended up being an inspiration for this blog.

Finally, when in doubt about when to apply SRP, ask which option will be more likely to maximise the simplicity of the codebase. Take a step back from your code and take a walk through your application’s structure. Better still, work in a pair or get it reviewed. It will quickly become obvious if you are applying SRP too sparingly or too much.

Finally, it is worth considering that SRP is only one of 5 principles in SOLID that aim to enable good code design. A recommended read is the Four Rules of Simple Design, which as the title suggests, takes an alternative, simple approach to designing software. The great thing is that considers all aspects of SOLID including SRP as well as other common theories of good software design.

Whilst the intent of single responsibility seems to have a sound basis, its implementation is potentially more tricky. The definition of SRP is fuzzy and open to misinterpretation, and even if the definition is well understood, applying SRP in day to day practice can have both positive and harmful effects. Successful implementation of SRP is more likely to happen if you consider the wider context of the application, the project lifecycle and ultimately, by adopting a policy of keeping your codebase as simple as possible.

http://code.tutsplus.com/tutorials/solid-part-1-the-single-responsibility-principle--net-36074

http://www.oodesign.com/single-responsibility-principle.html

Software es nuestra pasión.

Somos Software Craftspeople. Construimos software bien elaborado para nuestros clientes, ayudamos a los/as desarrolladores/as a mejorar en su oficio a través de la formación, la orientación y la tutoría. Ayudamos a las empresas a mejorar en la distribución de software.