- Por Matt Belcher

- ·

- Publicado 09 Jun 2020

This article was inspired by SCLConf 2019 and covers in more detail the lightning talk I gave at an LSCC meetup recently. Thank you to those who listened to the talk I created (quite quickly) between the conference and attending the meetup.

It is for those who want to improve their decision making when it comes to software architecture.

In July 2016 Eddie Hall achieved something no man before him had, managing to deadlift 500kg (or half a ton). The year before, he broke his own world record by lifting 465kg. He was no stranger to the deadlift, and no stranger to breaking world records.

You see, what Eddie achieved does not happen by magic. All of the training, and the eating was centred around becoming one of the strongest men in history. In order to do this he had to decide what he wanted to optimise. Eddie was required to be strong, for a very short amount of time. Therefore, it would make no sense for him to try and be the best 800m runner. If running was not going to contribute to his goal, you can bet he was not going to do it. The same goes for his structure (or physical architecture). He was consuming enough calories to enable him to be strong, not to have washboard abs.

You might be wondering something like "the above is interesting, but how does it relate to software architecture?". Well, for now the key takeaway should be that like Eddie, we must decide what we are optimising for when building software. I am sure Eddie would love to be a world class sportsman in all sports, however it is not practical in reality and we must decide what we actually want. An appreciation of this can help to avoid chasing "snake oil" and "silver bullets".

So enough about deadlifts, let's move on to discuss some software!

Many of you reading this will have been involved in (or aware of) discussions around which architecture to choose. Often, someone might suggest using the thing that is new and shiny, and a game of buzzword bingo commences, where you will hear phrases such as the below:

In general, discussions usually become ineffective when the people in the room do not have sufficient information to make sensible decisions. With respect to architecture, it is usually that people do not have enough context around what they need to optimise for. That's a concise way of putting it, but let's look at a few examples to further illustrate what is meant by this.

Imagine you are part of a team to produce a proof of concept using 3D technology for presentations (via a headset). The key here is to understand the context, which is you are creating this PoC to prove a concept. This means you need to optimise everything you do to contribute to that goal. Below we will look at what bad might look like:

As previously mentioned, once we understand what is to be achieved - validating a concept - then we can make sensible decisions, removing waste and focus on what really matters. If we can run a presentation using 3D technology, then we have done enough to enable the experiment to commence (which can be done multiple ways). On the contrary if we spend too much time discussing architecture, we are losing time that could be spent on producing something that can prove the underlying hypothesis of the project. Furthermore, people often underestimate how much time they have after delivering something tangible. Often there is a lull, where you can evaluate what you have produced. It is not normally the case that the person asking for the software product will then have an entire backlog ready for you to work on straight away. This is because they themselves have work to do, taking the product to show investors etc.

One should not spend too much time discussing architecture, without anything tangible to show. This however, does not mean we should not have architectural discussions, they just need to be tailored to the context. If the PoC was for a platform to help people manage microservices, then the architecture might be even more important and might warrant more focus. These conversations should still be centered around what is to be optimised for.

Similarly, choosing a programming language no one on the team knows just because you can is probably not the best idea. If it is a specialist language for developing 3D applications, which will in turn make the PoC easier to build and faster to validate, then this is much better reasoning. Otherwise, stick to what you have the skills for as it will mean you can just focus on the problem, and not get distracted with nuanced language features or syntax.

The last point has a hard truth to it. That is, if you have not yet validated the PoC, why spend more time polishing the code? If no one has validated it is useful and it could have some traction with a particular market segment, why waste effort? Furthermore, often PoCs are re-written post-validation as the focus is different. When producing a PoC the focus is usually to prove a concept (all in the name really), whereas the stage after this might be slightly different and this is where a bit more polish might be welcomed.

In another example, imagine you are tasked with producing a website to capture interest in a restaurant that is due to open soon. This is preferred to be done by people placing their email addresses, so they can be notified of updates and given vouchers for when it opens. Let's take a look at what bad might look like.

All the owners of the restaurant want is the ability to capture potential customers (using email addresses). Therefore, they want something that can be created quickly to provide this capability. For example, a static website could be created and hosted in something like Amazon S3, and add something like Mailchimp to take care of capturing interested members of the public.

Alternatively, you could provision an entire Kubernetes cluster for the website, however this might not be wise. By doing this you would be making some assumptions. One of which is that the restaurant business need such infrastructure to support their simple website. Another is that the restaurant are going to want to pay for the running of this, which will most likely not be true. You see, similarly to the previous example, the restaurant are also trying to validate something. The something being interest in their restaurant. Therefore, they are likely (and wise) to only want to have minimal investment in such activities at this stage.

If one of the optimisations of the restaurant business is to keep costs low, creating your own subscription process instead of using an off-the-shelf version should only be used when it can be proved that it is more economically viable than building it yourself.

The previous examples might have made you think, they might have made you roll your eyes in disagreement. Crucially, it must have made you think about past (or current) software endeavours and whether you understood what the customer actually wanted. If it did not then I have work to do! Therefore, let's take a look at what "they" - the customer - really wants.

What the customer wants: an ability for a member of the public to navigate to a web page and enter their email address, which will be stored somewhere so those details can be used. Okay, let's add some things that they want to make it a bit more concrete:

The above will seem fairly straightforward to the restaurant owner, and in the context of other software projects, they don't actually want a lot! Let's now document what we (as developers) might want when we see the above:

Not everyone will think exactly the same as the above, but often it is the case. Often we don't make sound architectural decisions because we are optimising for what we want and not what the customer wants. Using something like React for the front-end might seem like a sensible (and fashionable) decision, but our context does not necessarily require it, making it a premature optimisation which for what the customer wants right now. Therefore, it is simply waste.

We have already discussed creating our own subscription process in the previous section, so I won't labour the point here.

To make sound architectural decisions we must first understand what the customer (of our software) wants. The examples previously discussed do somewhat simplify the real world. For example, say someone in your company wants X, you will make decisions based off of the information you have about X. But what if someone else in the company wanted something similar to X? Would this affect the decisions you make in terms of architecture? Quite possibly. Therefore, I will describe certain factors that might shape what you optimise for.

How teams are (or going to be) organised within a company can have an impact on architecture. For instance, if you have a large amount of people who will be distributed, it might mean you opt for an architecture that gives them full autonomy.

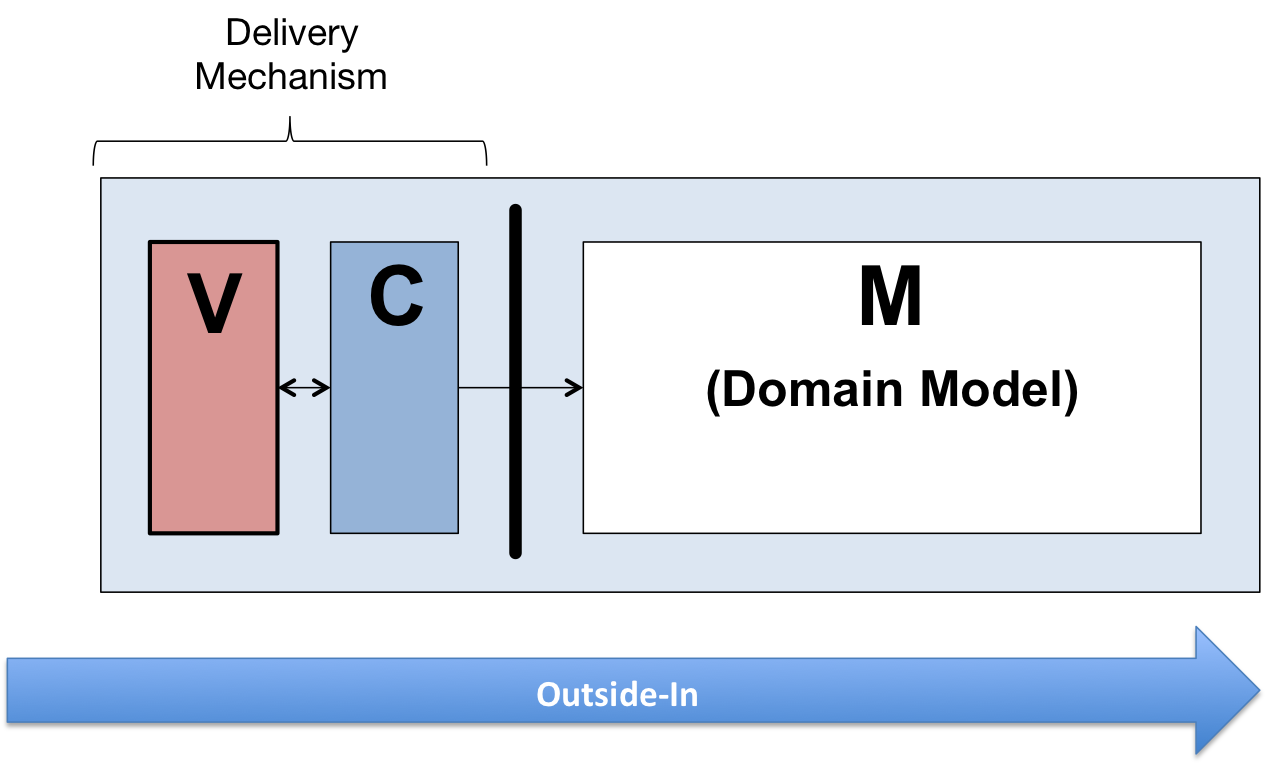

Closely related, if you find that teams are starting to step on each other's toes (accessing each other's database tables etc), you might want to introduce an architecture that establishes clear boundaries between teams (and their associated data). This could be a hard network boundary (via an API), or a softer boundary via a service within the codebase (e.g. one package talking to a service in another package in Java).

If you ever find yourself in a situation where you need to create a highly performant system, this will (and should) affect the decisions you make with your architecture. And architectural decisions will not just be confined to macro design (how you arrange your systems), but also at micro level, i.e. creating performant code. Even within the context of having to create highly performant systems, different approaches will be taken. For instance, some might spend more time focusing at the macro level, others might spend a bit more time (either through necessity) at the micro level, ensuring the code they write is optimal, in terms of performance.

Interestingly, optimising for performance is not simply about creating a system that performs its desired functionality in a timely manner. You see what that previous sentence says is: the system must be performant when it is running. This also means it must be running and ready to run its ultra performant code. This will further impact our architectural decisions because it is yet another aspect to optimise for.

There is of course a caveat. That is, when speaking to your customer (often referred to as "the business"), they will want to optimise for everything. The software must be high performance, ultra reliable. If you can name it, they will want it. The trick here is to understand what they actually want to optimise for, or is it? It's not, that sentence should read as the below:

The trick here is to understand what they need to optimise for

What can they simply not have if they want their software to provide the desired functionality? And then out of that (hopefully much smaller) list, what can be deferred for now. Hopefully, you will have a list of criteria which everything you do can be optimised for.

Similarly to Eddie, you are going to have to decide what you want to optimise for, otherwise you are going to be left wanting everything.

In this article we have taken inspiration from Eddie Hall and how he had to decide what he needed to optimise for. We have explored what can lead to ineffective discussions around architecture, and how we can ensure we don't fall into this trap. Furthermore, supporting examples were used in an attempt to illustrate what bad architectural decisions might look like. Hopefully as a reader you have appreciated the attempt to convey the importance of understanding your customer, and how decisions without the context of what is to be optimised can lead to the implementation of an ill-suited architecture.

Software es nuestra pasión.

Somos Software Craftspeople. Construimos software bien elaborado para nuestros clientes, ayudamos a los/as desarrolladores/as a mejorar en su oficio a través de la formación, la orientación y la tutoría. Ayudamos a las empresas a mejorar en la distribución de software.